from:

Prestel museum guide, text by Denise Daenzer and Tina

Wodiunig: Native Museum of Zurich (orig. German:

Indianermuseum Zürich / Indianermuseum der Stadt Zürich);

Prestel edition; Munich, New York 1996; supported by

Cassinelli Vogel foundation, Zurich, by MIGROS percent for

culture, by Volkart foundation in Winterthur; ISBN

3-7913-1635-4

Karl Bodmer,

painter of natives

[1832: Karl Bodmer invited

for a trip to Boston]

[A German prince writing a letter to a member of Zurich

upper class]:

"Some days ago I got the news from Rotterdam that a

beautiful American ship is prepared there for leaving in

some days to Boston. I will take my trip with this ship I

think. I don't know if I told you already that Mr. Bodmer

from Zurich will be in my staff. He will surely make a big

quantity of great paintings. In animal painting he was not

so good, but considering his probes given to me it seems

that he can draw, and I will offer him this opportunity."

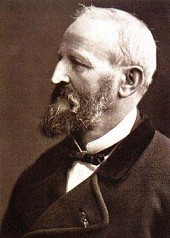

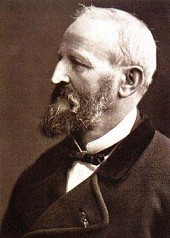

Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied, portrait [1]

|

|

Karl Bodmer, profile, 1877 [2] |

[Karl Bodmer - trip with

prince Prinz Maximilian zu Wied]

These lines of April 1832 were written by prince Maximilian

zu Wied (1782-1867) to Heinrich Rudolf Schinz, a Zurich

scholar and later professor for Nature History at Zurich

University. Mentioning "Mr. Bodmer" this is probably Karl

Bodmer, born in Zurich at 11 February 1809, coming from a

weaver's and cotton commerce family, and his artist

education had been with his uncle Johann Jakob Meier, a

pupil of Heinrich Füssli, and this Mr. Füssli was one of the

most famous Swiss painters of these times. When young Mr.

Bodmer presented his first works as a painter and drawer

augmenting his reputation, prince Maximilian paid attention

to him. This Prussian aristocrat was enjoyed by natural

history from youth on, and - by a date with famous

geographer and researcher Alexander von Humboldt - he had

been visiting Brazil between 1815 and 1817. [Napoleon's wars

had been over in 1815 and whole Europe was suffering and in

ruins, but he went to Brazil...]

|

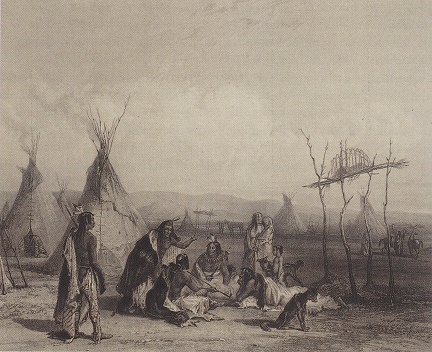

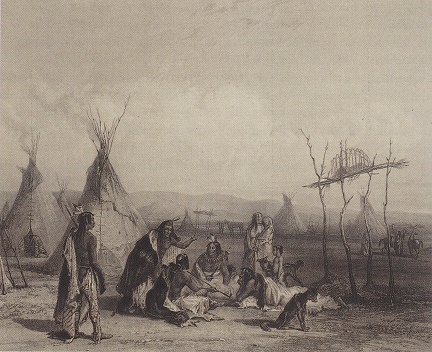

Karl Bodmer, platform funeral of a Sioux chief

Platform funeral

was the first funeral. It was applied like tree

funeral. The dead body was in furs and in the

height protecting the dead body from animals.

The dead body was mummified by this. Only two or

three years later the dead body (mummified) was

taken down and put into Earth with another

ceremony. But there were other tribes directly

burrying the dead body into Earth.

|

|

[In these times the reduction

of primary nations is going on already]

Maximilian's

second trip to the New World (1832-1834) was with young

Bodmer, and also a person named Dreidoppel ("Three Double"),

the prince's forester and hunter - and the aim of the trip

were the natives of upper Missouri. They hat colorful

clothes, singular weapons and mysterious rites who hardly

any white person had seen until these times. There were only

rumors. But they also had heard of the dreadful fights with

white settlers, of disastrous destructions and of the

introduced illnesses. Until that time there were about two

million natives in the Western prairies of North America,

but there were indications already that their culture will

not be possible to survive.

Karl Bodmer was not the only painter of these times painting

a record of these North American natives for future times.

Also Swiss man Peter Rindlisbacher who had emigrated with

his parents from Emmental to Canada, and also American

painter George Catlin, a critic of white reservation's

policy provoking many enemies, were documenting native

society and culture with illustrations.

[Trip until Fort McKenzie -

stay with primary nations of Mandan and Hidatsa]

The ship called Yellowstone was a fur trader ship, The

prince with his crew was traveling passing Ohio river and

Mississippi river reaching Missouri river up to the north.

And every time when the ship had to make a stay because of

wood and food supply the three were striving the region

collecting interesting plants and stones and getting into

contact with the dwellers. Bodmer mainly made layouts and

drawings. After a trip of 75 days they reached Fort Union,

the most important trade center of the fur companies. For

going on with the trip another more little ship was needed

passing only and clefted river landscape. Wind was only

rarely strong, so sailing was not often but the ship had to

be drawn with ropes or pushed with rods. Therefore the next

station was reached only in 34 days - the little hamlet of

Fort McKenzie where tour group stayed for some weeks.

Karl Bodmer, Fort Pierre at Missouri river

View of Fort

Pierre at Missouri river. At this point of the

river prince Maximilian and his two companions

had to leave the fur trade ship "Yellowstone"

because there were furs to trade bringing them

back to St. Louis - among others were 7,000

bison furs.

|

|

The original project going up to the Rocky Mountains staying

winter there was given up on half the way because there was

war between the Blackfoot and the Assiniboin [primary

nations] and the situation was really dangerous there.

Therefore the three travelers decided to go back staying

winter in Fort Clark more in the south. During the following

months Maximilian and Bodmer had enough opportunities for

talks and studies with life of the local natives of Mandan

and Hidatsa.

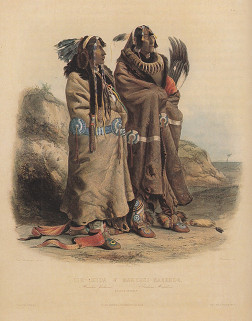

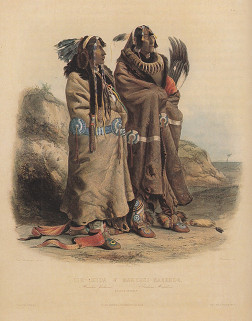

Karl

Bodmer, two Mandan natives

Rapidly there

was the rumor spreading within Mandan population

that Maximilian zu Wied and Karl Bodmer had come

to get to know the local population and for

drawings. Some appreciated the pictures, others

were skeptical and got afraid contemplating the

competed pictures. Bodmer had a friendship with

Sih-Chida (Yellow Feather) who was as old as he,

a son of a died Mandan chief. The two young men

made some excursions, but mostly Sih-Chida liked

to be with Bodmer at the evening trying

sketching pictures of his life. Some of his

drawings are possession of Northern Natural Gas

Co. collection in Omaha [at Missouri river at

the east of Chicago].

|

x

|

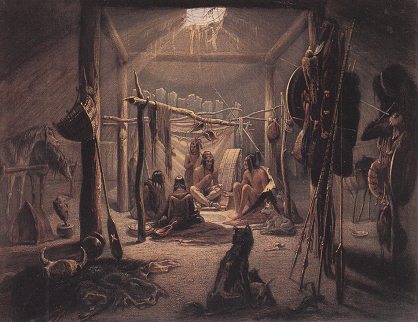

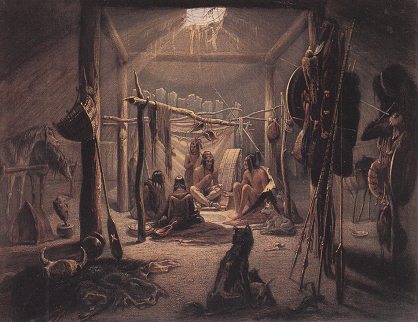

Karl

Bodmer, Mandan natives in a pithouse

We thank Karl

Bodmer a unique authentic presentation of inner

life in this Mandan pithouse. The level was a

little deeper than earth lever reaching it by a

little tunnel. Behind the door which was made by

wooden frame and fur there was a wall with

willow twigs protecting from the wind. In the

center of the room was the fire with a stony

frame, and in the roof's cupola there was the

hole for the smoke [and this was the only window

of the house]. During bad weather the hole was

shut by a bully boat [round river boat]. Also

horses were often taken into the inner of the

house protecting them from cold and theft.

|

|

|

|

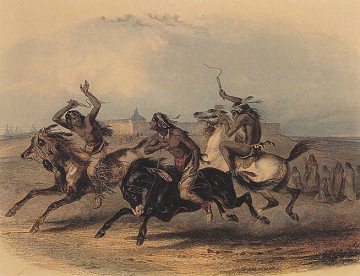

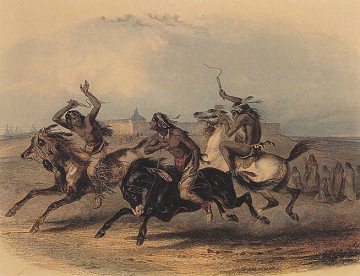

Karl

Bodmer, horse race in the region of Fort Pierre

- theft of horses had a tradition, as also

exchanging children for horses

Horses were

introduced by Spaniards in North America [coming

from today's Mexico, and also Texas and

California were Spanish territories at these

times]. In 1630 already the first horses came

into native's possession. Most of them were

stolen and in some cases they were exchanged -

also for children. Southern Ute and Comanche

were rated as the most successful horse thieves

and exchanged the animals with the northern

tribes. At about 1750 most of the prairie

natives possessed horses, and since about 1775

there were also bigger herds in the Northern

Plains.

|

|

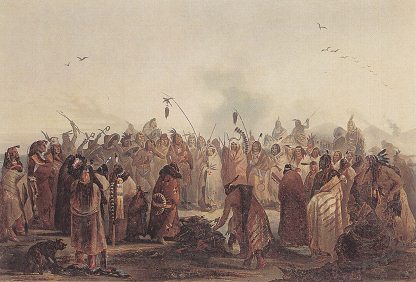

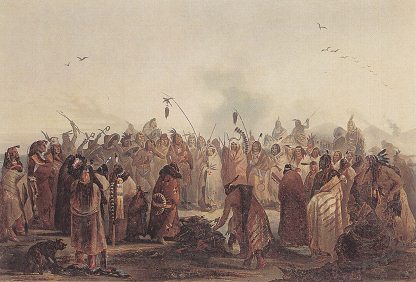

Karl

Bodmer, a scalp dance of Hidatsa natives killing

two horse thieves who were stupid getting

catched

Theft of horses

was a well loved test of courage gaining a big

honor - or losing the scalp and mostly also

losing life getting catched. Here in Fort Clark

two horse thieves of Assiniboin primary nation

were killed. The chief slayed the horse thief

and the chief's wife had the scalp fixed on the

top of a rod. The second scalp was shown by

another woman. When Hidatsa with their black

colored faces were acting with their drums and

rattles, the women and men began singing and

dancing.

|

There were endless drawings and watercolors during the whole

trip with impressive landscape and genre paintings,

illustrations of dances and rites, with studies of plants

and animals, with sketches with weapons and tools, and above

all great portraits and presentations of groups of natives.

After a hard winter - with emergency food of cornmeal and

biscuits also for the prince for some time - the group was

beginning traveling home since April 1834: with boxes full

of clothes, objects, plants, minerals and precious objects

of arts and cults which were collected and recovered by

exchange or as a present.

[Going home and exhibitions

of the objects of Mandan and Hidatsa culture - picture

atlas with Bodmer's pictures]

A part of the good was destroyed by a fire on board of the

ship, but the result of the scientific trip remained well

varied. Coming home on 25 August 1834 in royal castle

Neuwied in Germany the objects were well investigated and

systematically classified by prince Maximilian. Today most

of these objects can be found in the American sections of

ethnological museums of Berlin and in Linden Museum ("Lime

tree Museum") in Stuttgart - with the exception of the

nature study objects [plants and seeds].

The voluminous expedition report published by the prince

under the title "Trip to Inner North America in The Years

1832-1834" (orig. German "Reise in das Innere Nord-Amerika

in den Jahren 1832-1834") was published step by step between

1839 and 1844 in German, then in French and then in English

editions, with Bodmer's illustrations (p.10).

Add to this a picture atlas with Bodmer's pictures was

published in two volumes, and his colored copper engravings

were famous already. This picture atlas was produced in

collaboration with Zurich engravers Bayer, Hürlimann and

Weber, and also with French and English specialists.

[Bodmer's pictures

auctioned in 1959 in New York, with Maximilian's travel

diaries and printing plates - museum in Omaha - estate in

Newberry Library in Chicago]

After upcoming of photo cameras the pictures of Bodmer's

trip in America were forgotten more and more until the

originals came up in a revision in the castle library of

Neuwied. Anthropologist Josef Röder recovered them, and in

1959 New Yorker artist merchant M. Knoedler & Company

purchased the whole royal collection, with Maximilian's

travel diaries and the original printing plates of Bodmer's

drawings inclusive. Since 1986 the collection is in

possession of Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha. A little part of

about 40 sketches and watercolors is in Newberry Library in

Chicago which came from an auction of Bodmer's estate after

his death in Paris.

[Copper engravings]

Today the original Bodmer's picture atlas can be seen in

some European and North American museums and collections but

is rarely complete. Aside of this there are some different

sequences of Bodmer's native drawings and paintings coming

from different models of the original edition. Also Native

Museum of Zurich has got a precious collection of such fully

colored copper engravings.

In 1991 a London editor published a limited new edition of

81 copper engravings of Karl Bodmer with the title "Bodmer's

America" which is sold in Europe by Knobel Art Collections

in Zug (Switzerland). The 125 numbered pictures of this new

edition are made with the original printing plates and were

colored by hand according to the original models.

After returning home prince Maximilian wrote about Karl

Bodmer's work: "I have my doubts if there had ever been made

a collection of portraits and traditional clothes in this

manner how Mr. Bodmer made it. At least there does not exist

anything similar about North America, and the pictures have

really got a speaking similar style."

Bodmer never left Europe again. Some time later he changed

to France to Barbizon near Fontainebleau being member of a

local group of artists later known as "School of Barbizon",

and they were quiet successful painting in a style of

intimate landscape. Bodmer succeeded with watercolors and

landscape paintings, and also etchings of plants and animal

selling them to newspapers and reviews. Besides he worked

also for book editors illustrating works like the "93

fables" of La Fontaines and Victor Hugo.

[Last years in Paris -

death in 1893]

His last years of life Bodmer lived with his wife in a

little flat in Paris at Deferent Rochereau Square 24 where

he died at 30 October 1893, mostly forgotten and

impoverished. (p.11)

Karl

Bodmer, two Mandan natives

Karl

Bodmer, two Mandan natives