[Territorial Developments]

MORAVIA (Czech Morava, Ger. Maehren), central region of

*Czechoslovakia.

A political unit from around 769, it formed the nucleus of

the Great Moravian Empire (first half of the ninth century

until 906). From 1029 it was under Bohemian rule, then in

1182 it became a margravate [[county]] and as such a direct

fief [[feudal tenure]] of the Great Moravian Empire (first

half of the ninth century until 906). From 1029 it was under

Bohemian rule, then in 1182 it became a margravate

[[county]] and as such a direct fief of the empire.

Together with *Bohemia it became part of the *Hapsburg

Empire (1526-1918), and then part of Czechoslovakia, united

with former Austrian Silesia after 1927. Between 1939 and

1945 it was part of the Nazi-occupied Protectorate of

Bohemia-Moravia after parts had been ceded to Germany as a

result of the Munich Agreement of September 1938. It has

been replaced, in 1960, by the establishment of two

provinces, southern and northern Moravia. Partly because of

the region's location on the crossroads of Europe,

throughout the centuries there was a considerable amount of

reciprocal influence between Moravian Jewry and the Jewries

of the surrounding countries.

It had a thriving cultural life, promoted by the high degree

of autonomy and communal organization it developed. Moravian

Jews played a large part in the development of the

communities in Vienna and northwestern Hungary.

From the Early Settlement

to the 17th Century. [Roman times - reports from the

Middle Ages]

Documentation of the first stages of Moravian Jewry is very

scanty [[little]]. In all probability Jews first came to

Moravia as traders in the wake of the Roman legions.

According to tradition some communities (e.g. *Ivanice,

*Jemnice, *Pohorelice, and *Trebic) were founded in the

first millennium, C.E. but such reports cannot be

substantiated. Moravia is mentioned rarely in early medieval

Jewish sources. However, it may well be that some

authorities confused part of Bohemia with Moravia.

As other authorities referred to all Slav countries as

"Canaan", it is difficult to make any positive

identification of a Jewish settlement in Moravia. It is

likely that Jews lived in Moravia before the date of

conclusive documentary evidence for their presence. In the

biography (col. 295)

of Bishop Clement of Bulgaria (d. 916) it is reported that

after the death of the Byzantine missionary Methodius (885),

when the Frankish Church prevailed in the Byzantine Empire,

about 200 Slav priests weer sold to Jewish slave traders.

The Raffelstaetten toll regulations (903-906), which fixed

relations between the Great Moravian and the Carolingian

empires, mention Jews as slave traders, but do not say

whether they resided in Moravia.

According to the Bohemian chronicler Cosmas of Prague

(1039?-1125), a baptized Jew built the Podivin castle in

southern Moravia in 1067; Cosmas also mentions a community

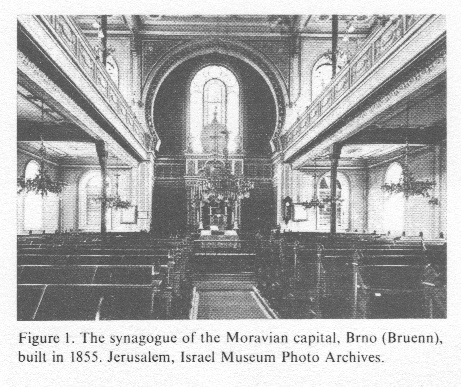

in *Brno (Bruenn) in 1091. *Isaac Dorbelo, a student of R.

Jacob b. Meir *Tam, speaks of observing the rite of the

*Olomouc (Olmuetz) community around 1146 (

Mahzor Vitry, Hurwitz

ed. (1923), 247, 388).

The first extant document explicitly mentioning Jews in

Moravia is the *Jihlava (Iglau) city law of 1249. In 1254

*Premysl Ottokar II issued his charter, an adaptation of one

originally issued in 1244 by Duke Frederick II of Austria

(1230-46). Among other provisions it forbade forced

conversion and condemned the *blood libel. A gravestone

excavated in **Znojmo (Znaim), dated 1256, is the oldest

known Jewish tombstone from Moravia.

In 1268 Premysl Ottokar II renewed his charter; at the time

the Jews of Brno were expected to contribute a quarter of

the cost of strengthening the city wall. In an undated

document (probably from c. 1273-78) he exempted the Brno

Jews from all their dues for one year since they had become

impoverished. Writing to the pope in 1273, Bishop Bruno of

Olomouc complained that the Jews of his diocese employed

Christian wet nurses, accepted sacred objects as pledges

[[commercial deposit]], and that the interest they took

during one year exceeded the initial loan.

The first time a Jews Nathan, is mentioned by name is in

1278, in connection with a lawsuit about church property.

Solomon b. Abraham *Adret (d. 1310), responding to a

question addressed to him from Moravia, mentions the

*Austerlitz (Slavkov) and *Trest (Triesch) communities.

Wenceslaus II confirmed Premysl Ottokar's charter (1283 and

1305) "at the request of the Jews of Moravia".

[Jews in Moravia since the

14th century: moneylenders, trade - immigration of German

Jewish refugees from Black Death expulsions]

When Moravia passed under the rule of the Luxembourg dynasty

in 1311, the Jewish community of Brno, carrying their Torah

Scrolls, participated in the celebration welcoming King John

of Luxembourg to the city. In 1322 John permitted the bishop

of Olomouc to settle one Jew in four of his towns (*Kromeriz

(Kremsier), Mohelnice, Vyskov, and Svitavy (Zwittau)), and

to benefit from their tax payments. At that time Jews earned

their livelihood mainly as moneylenders, but gentile

[[non-Jewish]] moneylenders could also be found.

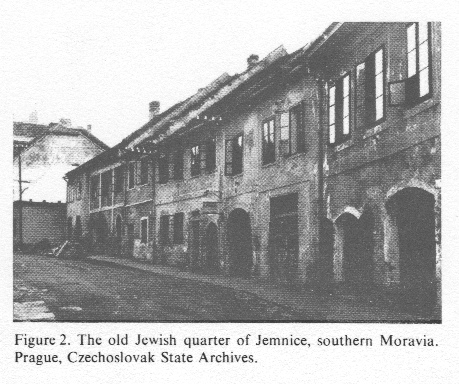

Several Moravian communities, such as Jemnice (Jamnitz),

Trebic, and Znojmo, were affected by the wave of massacres

evoked by the *Pulkau *Host desecration in 1338. A toll

privilege granted in 1341 to the monastery of Vilimov, which

was on the main road between Moravia and Bohemia, puts

Jewish merchants on a par with their gentile counterparts

and mentions a great variety of merchandise in which they

dealt.

*Charles IV granted the cities of Brno and Jihlava the right

to admit Jews in 1345, making the Jihlava community

independent of that in Brno. There was an influx of Jews

fleeing from Germany into Moravia during the *Black Death

massacres (1348-49). In 1349 the bishop of Olomouc

complained to the city authorities that Jews did not wear

special Jewish hats, as they were supposed to do. Between

1362 and 1415 Jews were free to accept real estate as

security on loans.

[Austrian Jewish refugees -

ban from the "royal cities" 1454-1848 - settlements in

villages - Turkish wars]

Some of the Jews expelled from Austria in 1421 (the

*Wiener Gesera) settled

in Moravia. Accused of supporting the *Hussites, the Jihlava

community was expelled by Albert V, duke of Austria and

margrave [[count]] of Moravia, in 1426. As a result of John

of *Capistrano's activities, the Jews (col. 296)

were expelled from five of the six royal cities in 1454

(Jihlava, Brno, Olomouc, Znojmo, and Neustadt; the sixth

royal city, Uherske Hradiste, expelled the Jews in 1514).

The royal cities remained forbidden to them until after the

1848 revolution. The Jews who were expelled settled in the

villages. During the 16th century, when there was no central

power in Moravia ("in every castle a king"), the Jews were

settled in small towns and villages under the protection of

the local lords. The latter treated them well, not only

because of the part they played in the economic development

of their domains, which they shared initially with the

Anabaptist communes, but also because one of the lords

belonged to the Bohemian Brethren (see *Hussites) or were

humanists; many therefore believed in religious tolerance.

The importance of the Jews in the Moravian economic life (as

military purveyors and *Court Jews) increased because of the

constant threat to the Turkish wars. Since several Christian

sects lived side by side it became somewhat easier for the

Jews to pursue his own interests without interference.

[Thirty Years' War: Jews

take over "Christian" houses - heavy suffering - refugees

from the Chmielnicki massacres 1648 and from the expulsion

from Vienna 1670 - crafts, trade and markets]

When the Anabaptists were expelled (1622), and the country

became depopulated during the Thirty Years' War (1618-48),

the Jews took over new economic areas and were also

permitted to acquire houses formerly occupied by "heretics".

However, at the same time some communities suffered severely

during the war (e.g., Kromeriz and *Hodonin (Goeding)).

Moravia also absorbed refugees from Poland after the *

Chmielnicki

massacres (1648), among them scholars such as Gershon

*Ashkenazi, author of

Avodat

ha-Gershuni, and Shabbetai Kohen, author of

Siftei Kohen, the

renowned commentary on the Shulhan Arukh, who became rabbi

of Holesov. Many Jews also arrived after the expulsion from

Vienna (1670).

At this time an increasing number of Moravian Jews were

engaged in crafts, a process that had already begun in the

16th century, and the cloth and wool merchants and tailors,

who made goods to be sold at fairs, were laying the

foundations of the textile and clothing industry for which

Moravia was later known. In 1629 *Ferdinand II permitted the

Jews to attend markets and fairs in the royal cities, on

payment of a special body tax (

Leibmaut; see

*Leibzoll); in spite of protests from the

guilds and merchants, the charter was renewed in 1657, 1658,

and 1723. Jews also attended fairs outside Moravia,

especially those in *Krems, *Linz, *Breslau (Wroczlaw), and

*Leipzig.

In 1650 the Moravian Diet decided that Jews might reside

only where they had been living before 1618, but the

decision was not enforced. Later this was modified by the

Diet of 1681 to permit Jews to dwell where they lived before

1657.

The Modern Era.

[anti-Jewish fine decrees and trade decrees by Charles VI

- separation laws]

On July 31, 1725, during the reign of Charles VI, an

imperial order fixed the number of registered (col. 299)

Jewish families at 5,106 and threatened any locality which

accepted Jews where they had not been previously settled

with a fine of 1,000 ducats.

On September 20 of that year the same penalty was imposed on

anyone who allowed Jews to come into possession of real

estate, particularly customhouses, mills, wool-shearing

sheds, and breweries. The first enactment was reinforced a

year later by allowing only one son in a family to marry

(see *Familiants Law); the second was never carried out as

it would have deprived noblemen of lucrative revenue and

most Jews of their livelihood. Under Charles VI the

geographical separation of the Jews was implemented in most

Moravian towns.

[Maria Theresa laws]

*Maria Theresa threatened Moravian Jewry with expulsion

(Jan. 2, 1745) but rescinded [[withdraw]] her order,

permitting them to remain for another ten years. In 1748,

however, she raised their toleration tax (

Schutzgeld) from a

total of 8,000 florins (since 1723) to 87,700 for the next

five years and 76,700 in the following five; in 1752 the tax

was fixed at 90,000 florins. Two years later the empress'

definitive "General Police Law and Commercial Regulations

for the Jewry of the Margravate of Moravia " appeared; as

its name indicates it regulated all legal, religious, and

commercial aspects of Jewish life in Moravia. The authority

of the

*Landesrabbiner

[["chief rabbi"]] was defined and his election regulated, as

were those of the other offices of the

*Landesjudenschaft.

[["Jewry of the county"]].

[The council of Moravian

Jewry: the "heads", the chief rabbi at Mikulov - two

different councils]

In essence the law was based on a translation by Aloys von

*Sonnenfels of the resolutions and ordinances of the old

Council of Moravian Jewry. Although the earlies recorded

session of the council had taken place in 1651, it was at

least a century older, for a Bendit Axelrod Levi was

mentioned in 1519 as being "head of all Moravian

communities". The names of most Moravian rabbis were

recorded from the mid-16th century.

A clearer picture of the council emerges after the Thirty

Years' War (1618-48): Moravia (

medinah) was divided into three provinces

(

galil), in each of

which two heads (

rashei

galil) officiated; at the same time, each one was a

member of the governing body of Moravian Jewry (

rashei ha-medinah). The

chief authority was the

Landesrabbiner

(rav medinah) [["chief rabbi"]] who had

jurisdiction over both secular and religious matters. His

seat was in *Mikulov (Nikolsburg). His presence at council

sessions was obligatory and he was the authoritative

interpreter of their decisions.

There were two types of council: the governing "small"

council of six heads of provinces, and the "large"

legislative one, which was attended by representatives of

the communities and met every three years at a different

community. The franchise was very limited and the

council oligarchic in spirit and practice. The last "large"

council, that of 1748, was attended by 61 representatives

elected by 367 houseowners. Its main function was the

election of small bodies of (col. 300)

electors and legislators. The authority of the council was

undermined by the absolutist state, which in 1728 defined

its ordinances as "temporary";

[The limitation of

independence of Jewish communities under Maria Theresa

since 1754 - further chief rabbis - schools - spiritual

metropolis of Nikolsburg and other schooling centers]

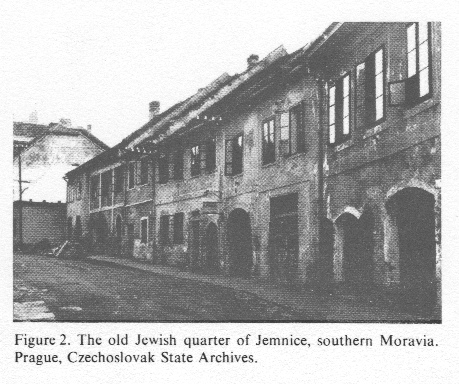

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moravia, vol. 12, col. 300,

the old Jewish quarter in Jemnice, southern Moravia

from 1754 Maria Theresa limited the independence of the

communities and their central council. The main function of

the council and the

Landesrabbiner

was to divide the tax load justly among the communities.

When

Landesrabbiner Menahem

*Krochmal was called upon to settle a dispute between the

poor and the rich over the control of the communities he

claimed that the decisive voice belonged to those who

contributed more to the community. Krochmal's tenure

(1648-61) was vital in the formulation of the 311 ordinances

(

shai takkanot) of

the Moravian council. Among his noted predecessors were R.

*Judah Loew b. Bezalel (Maharal) and R. Yom Tov Lipmann

*Heller. Among the more distinguished holders of the office

were David *Oppenheim (from 1690 to 1704); Gabriel b. Judah

Loew *Eskeles, nominated in 1690; and his son Issachar

Berush (Bernard) *Eskeles, (d. 1753), who also became chief

rabbi of Hungary and successfully averted [[stopped]] the

1745 expulsion threat.

His successor, R. Moses b. Aaron *Lemberger, ordained that

henceforth at least 25 students should attend the Mikulov

(Nikolsburg) yeshivah [[religious Torah school]], and that

each Moravian sub-province should support two yeshivot with

ten students each. R. Gershon Pullitz and R. Gershon *Chajes

(

Landesrabbiner

1780-89) fought against the insidious influence of

Shabbateanism and Frankism in Moravia: in 1773 Jacob *Frank

resided in Brno, where the *Dobruschka family were among his

adherents; members of the *Prostejov (Prossnitz) community

were commonly called

Schebse

since so many of them were followers of Shabbetai

Zevi.

In spite of the hostile attitude of Charles VI and Maria

Theresa and the continuous curtailment of the authority of

the council and the

Landesrabbiner,

there was a thriving communal life in Moravia. In the first

half of the 19th century the

Landesrabbineren Mordecai *Benet (d.

1829), Nehemiah (Menahem) Nahum *Trebitsch (d. 1842), and

Samson Raphael *Hirsch (served from 1846 to 1851) wielded

[[had]] great influence. Besides the spiritual metropolis of

Nikolsburg, there were important centers of learning in

Boskowitz (*Boskovice), Ungarisch-Brod (*Uhersky Brod),

Kremsier, Leipnik (*Lipnik nad Becvou),and Prossnitz. (col.

301)

The restrictions imposed on the Jews by Charles VI and Maria

Theresa, most of which remained in force until the second

half of the 19th century, led many Moravian Jews to leave

the country, mainly for Hungary (Slovakia) and later for

Austria. (S.302)

[Toleranzpatent under

Joseph II - limited number of licensed Jewish families -

"royal cities" remain closed]

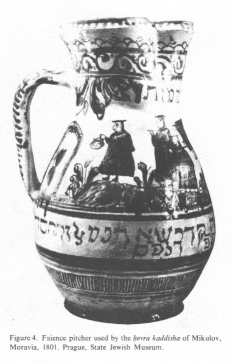

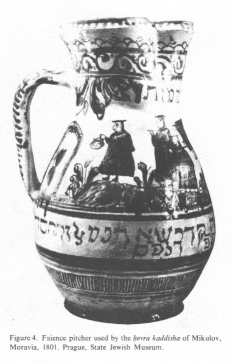

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

(1971): Moravia, vol. 12, col. 304, faience pitcher

used by the hevra kaddisha of Mikulov, Moravia, 1801

The situation of Moravian Jews improved after Joseph II's

*Toleranzpatent, which

abolished the body tax (see

*Leibzoll) and other special taxes and

permitted some freedom of movement. But the limitation of

the number of Jewish families remained, the number of

licensed (

systematisiert)

Jewish families being kept at 5,106, later raised to 5,400.

An edict of Francis II in 1798 limited their rights of

settlement to an area of 52 Jewish communities (

Judengemeinden), mostly

in places where communities had existed from early times.

The six royal cities remained closed to the Jews.

Like most of the local Christian communities, the Jewish

communities were subject to the authority of the feudal

lord. At that time the largest communities were Mikulov with

620 families, Prostejov with 328, Boskovice with 326, and

Hlesov with 265. The total number of registered Jews

increased from 20,327 in 1754 to 28,396 in 1803 (the actual

numbers might have been from 10 to 20% higher). (col. 301)

In 1787 Joseph II ordered that half of the main tax on

Moravian Jewry (then 88,280 florins) be allowed to

accumulate in a fund (known as

Landesmassafond) for the payment of the

Landesrabbiner [[chief

rabbi]] and other officials. (col. 302)

[[Napoleon 1800-1815 and his revolutionary legislations are

not mentioned]].

In 1831, when the fund was sealed, the capital was allocated

for low-interest loans for needy communities. (col. 302)

[1848: commercial

emancipation and anti-Jewish riots - self-defense units -

new municipal laws - new communities in the cities]

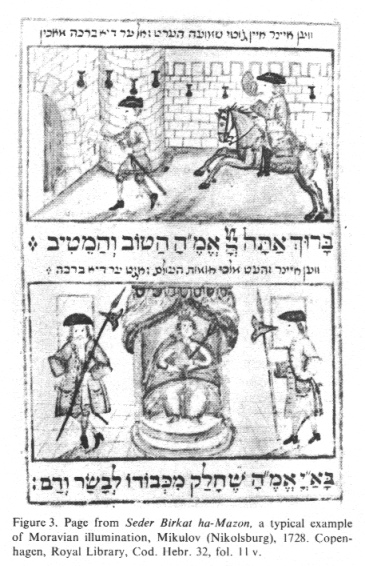

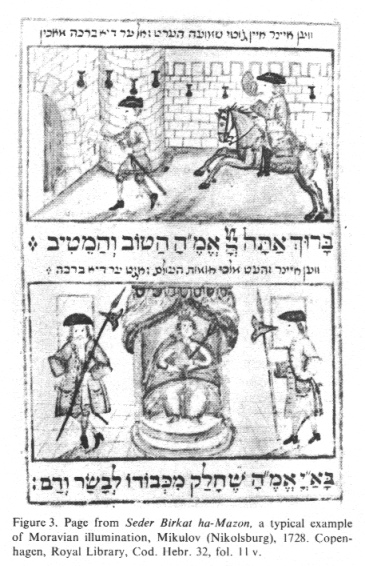

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moravia, vol. 12, col. 303,

illustration of 1728: Page from

Seder Birkat ha-Mazon, a typical example

of Moravian illumination, Mikulov (Nikolsburg), 1728

The revolutionary year of 1848 brought the abolition of most

legal and economic restrictions, the right of free movement

and settlement, and freedom of worship, but also gave rise

to anti-Jewish disturbances: in Prostejov a Jewish national

guard, 200 men strong, was organized. These measures of

freedom were enacted by the Austrian parliament which

convened in Kromeriz. Landesrabbiner [[chief rabbi]] S. R.

Hirsch sent two messages to parliament. The process of legal

emancipation was completed in the Austrian constitution of

1867.

In conformity with the new municipal laws (col. 301)

(passed temporarily in 1849 and definitively in 1867) 27 of

the 52 Jewish communities were constituted as Jewish

municipalities (

*politische

gemeinden) with full municipal independence, and

existed as such until the end of the Hapsburg monarchy, in

striking contrast to the abolition of Jewish municipal

autonomy in Prague in 1850 and in Galicia in 1866. The

legalization of the Jewish religious autonomy, a longer

process, was not completed until 1890, when 50 Jewish

religious communities (

Kultusgemeinden)

were recognized, 39 in places where old communities existed

and 11 in newly established Jewish centers. (col. 302)

After equal rights and freedom of movement were granted new

communities were established in the big cities of Brno

[[Bruenn]], Olomouc, Ostrava (Maehrisch Ostrau), and

Jihlava, while others were set up in small places that

previously Jews had only visited on market days. At the same

time many Moravian Jews left for other parts of the Hapsburg

Empire, particularly Vienna, and some emigrated. As a

result, the Jewish population of Moravia remained relatively

static at a time when the world Jewish population was

rising, and even declined slightly from 1890 [[probably

because of emigration waves]]. (col. 302)

Table:

Number of Jews in Moravia

|

Year

|

Number

of

Jews

|

1830

|

29,462

|

1840

|

37,316

|

1848

|

37,548

|

1857

|

42,611

|

1869

|

42,644

|

1880

|

44,175

|

1890

|

45,324

|

1900

|

44,255

|

1910

|

41,255

|

1921

|

37,989

|

from: Moravia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica

(1971), vol. 12, col. 302

|

[The reorganization of the

fund (Landesmassafond) - professions in trade and

industries - Rothschild]

An assembly of 45 Moravian communities convened in 1862 in

order to try to obtain control of the fund

[[Landesmassafond]], which was managed by state officials.

After protracted negotiations, *Francis Joseph I awarded the

guardianship of the fund (almost 1,000,000 kronen) to an

elected curatorium whose first chairman was Julius von

Gomperz of Brno [[Bruenn]]. This curatorium served in lieu

of a central Jewish organization until the collapse of the

Austrian regime and enabled Moravian Jewry to alleviate

[[reduce]] the lot [[masses]] of the declining small

communities.

Jews were mainly engaged in trade, but increasing numbers

entered some industries and the free professions or became

white-collar workers (mainly in undertakings owned by Jews).

They were prominent in the wool industry of Brno, the silk

industry of northern Moravia, the clothing industry in

Prostejov, Boskovice, and some other towns, the leather

industry, the sugar industry in central and southern

Moravia, and the malt industry in Olomouc.

The brothers Wilhelm and David von *Gutmann (originally from

Lipnik) developed jointly with the Rothschilds the coal

mines of Ostrava and established the great iron and steel

works there. The Rothschilds also built the Kaiser Ferdinand

Nordbahn, a railway linking Vienna and Galicia via Moravia

and Silesia. Consequently there was a substantial number of

Jewish railway engineers, employees, engine drivers,

licensees of railway restaurants, etc.

In the late 19th (col. 302)

and 20th centuries Jews were also prominent in the timber

industry and trade, the glass industry, hat-making, hosiery,

and even in the development of water power.

[The link between Moravia

and Vienna - languages - racist Zionism movement in

Moravia]

The close ties between Moravian Jews and Vienna persisted

until the end of the Austrian monarchy, and even increased

after emancipation, since Moravia had no university under

Austrian rule. Consequently, the great majority of Moravian

Jews spoke German. In 1900, 77% of all Moravian Jews

declared German as their mother tongue, 16% Czech, and 7%

other languages (mainly foreigners), but this did not

indicate any strong political assimilationist trend toward

Germany or hostility toward Czech nationalism. Jews

enthusiastically supported the candidacy of T.G. *Masaryk

for the Austrian parliament in 1907 and 1911. Students from

Moravian communities studying in Vienna were among the first

followers of Theodor Herzl and many Zionist associations

sprang up in Moravia, from the early days of [[racist]]

Zionism.

[[The events during First World War 1914-1918 are missing in

this article]].

[1918-1938: Moravia in the

CSSR - expanding racist Zionist organizations]

After the Czechoslovak Republic had been established in

1918, Moravian Jews frequently constituted the bridge

between the Jews in Bohemia on the one hand and those in

Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia on the other, between

traditionalists and modernists, Zionist and non-Zionists;

60% of Moravian Jews declared themselves as being of Jewish

nationality. The first provincial union of Jewish

communities was established in November 1918 under the

leadership of Alois *Hilf from Ostrava; this union became

instrumental in the emergence and consolidation of the

Jewish National Council as well as in the setting up of the

Supreme Council of the Jewish Religious Communities in

Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia. The Central Committee of the

Zionist Organization in Czechoslovakia had its seat in

Ostrava from 1921 to 1938, under the chairmanship of Joseph

*Rufeisen; the center of *He-Halutz was also located in

(col. 303)

Ostrava and the main office of Keren Hayesod in Brno for a

long time. Brno had the only Jewish high school in the

western part of Czechoslovakia and Ostrava had a fully

equipped vocational school. Moravian Jews were represented

by a Zionist in the provincial Diet. However, the number of

Jews continued to decline, from 45,306 in Moravia and

Silesia in 1921 to 41,250 in 1930 [[probably because of

emigration movement provoked by the racist Zionists]],

almost half of whom were concentrated in the three cities

Brno, Ostrava, and Olomouc. The venerable communities

dwindled or even disintegrated.

[NS occupations 1938-1945 -

holocaust]

When the Germans occupied Austria in March 1938, several

thousand Jews escaped to Moravia, mainly to Brno. They were

followed in September and October of that year by a few

thousand more from the areas detached from Czechoslovakia

and incorporated in Germany by the Munich Agreement. The

majority of Jews in the Teschen (Tesin; Cieszyn) district,

ceded to Poland, did not flee.

On March 15, 1939, the remaining parts of Moravia were

occupied by Nazi Germany and became part of the Protectorate

of Bohemia-Moravia. Immediately after the conquest, the lot

of the Jews in northeast Moravia was especially disastrous.

They constituted a high percentage of those expelled to the

Nisko reserve in the Lublin area. Many perished there in the

first winter of the war; others returned, only to join their

fellows in *Theresienstadt and various extermination camps.

(col. 304)

For fuller details on the holocaust period see *Protectorate

of Bohemia-Moravia. (col. 305)

[1945-1971]

After the war, very few survivors returned to Moravia, and

the majority of them later emigrated to Israel and other

countries.

[[The mass flight after 1945 to the DP camps and the

emigration wave to racist Herzl Israel and other oversea

countries is not mentioned. The communist reign since 1948

and the heavy anti-Semitism under the communist regimes as a

general punishment for the foundation of racist Zionist Free

Mason CIA Herzl Israel is not mentioned. By this the

remaining Jewish youth was lead for integration, mixed

marriages and change of religion and the number of Jews in

Moravia was more and more reduced. There were also some

emigrations permits, see: *

Czechoslovakia

1945-1971 ]].

In 1970 barely 2,000 Jews remained in former Moravia, the

largest community being in Brno [[Bruenn]]. Brno was also

the seat of the chief rabbi for Moravia, Richard *Feder, who

later became chief rabbi of Czechoslovakia. When he died in

1970, at the age of 95, the rabbinate remained vacant. The

Jewish museum of Mikulov, established shortly before World

War (col. 304)

II, was reconstituted as part of the state museum; another

Jewish museum was established by the state in Holesov.

For fuller details on the contemporary period see

*Czechoslovakia. [...] (col.305)

Table: List of alternative

names for places shown on map

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moravia, vol. 12, col. 304, faience pitcher