The badge, hat and clothing laws for Jews in the Middle Ages

How the criminal "Christian" Church introduced special marks for Jews to prevent inter religious sex relationships

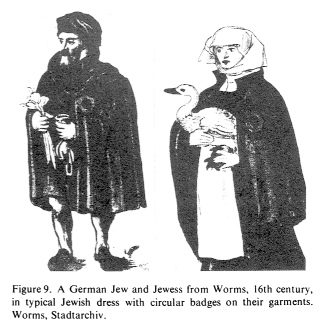

Jew with Jewish badge in yellow ring form (circular badge), Worms 16th century

Jewish woman with Jewish badge in yellow ring form (circular badge), Worms 16th century

from: Badge, Jewish; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 4

presentation by Michael Palomino (2007)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

<BADGE, JEWISH, distinctive sign compulsorily worn by Jews.

The first religious marks were imposed by Muslim rulers

Muslim World

[Vestimentary distinctions of different colors]

<The introduction of a mark to distinguish persons not belonging to the religious faith of the majority did not originate in Christendom, where it was later radically imposed, but in Islam. It seems that Caliph Omar II (717-20), not Omar I, as is sometimes stated, was the first ruler to order that every non-Muslim, the dhimmi, should wear vestimentary distinctions (called giyar, i.e., distinguishing marks) of a different color for each minority group. The ordinance was unequally observed, but it was reissued and reinforced by Caliph al-Mutawakkil (847-61).

Subsequently it remained in force over the centuries, (col. 62)

[since 887/8: marks on the house doors: swines for Christians and donkeys for Jews - and yellow belts and special hats for the Jews]

887/8 compelled the Christians to wear on their garments and put on their doors a piece of cloth in the form of a swine, and the Jews to affix a similar sign in the form of a donkey. In addition, the Jews were compelled to wear yellow belts and special hats.> (col. 63)

Christendom.

1215: Lateran Council appeals for measures against sex between the religions

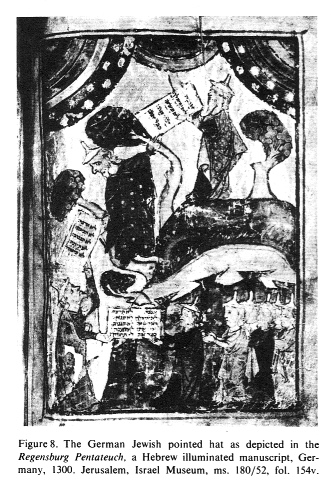

<Although written documentary testimony concerning distinctive signs worn by Jews from the 12th century is still lacking, pictorial representations of this (col. 63)

period, especially in the Germanic countries, introduce the pointed hat. This is subsequently referred to as the "Jewish hat", worn by Jews or depicted in allegorical representations of Judaism ("Synagoga"). It would seem, however, that this distinction was instituted by the Jews themselves.

Jewish ball pointed hat 01

Jewish ball pointed hat 02

There are some ambiguous references to the compulsory imposition of distinctive Jewish clothing in documents from the beginning of the 13th century (Charter of Alais, 1200: Synodal rules of Odo, bishop of Paris, c. 1200).

The consistent record, however, can be traced back only to canon 68 of the Fourth *Lateran Council (1215):

"In several provinces, a difference in vestment distinguishes the Jews or the Saracens from the Christians; but in others, the confusion has reached such proportions that a difference can no longer be perceived. Hence, at times it has occurred that Christians have had sexual intercourse in error with Jewish or Saracen women and Jews or Saracens with Christian women. That the crime of such a sinful mixture shall no longer find evasion or cover under the pretext of error, we order that they [Jews and Saracens] of both sexes, in all Christian lands and at all times, shall be publicly differentiated from the rest of the population by the quality of their garment, especially since that this is ordained by Moses. ..."

Both the allusion to biblical law (Lev. 19), and the inclusion of the canon among a series of others regulating the Jewish position, indicate that the decree was directed especially against the Jews.

Implementation of the council's decision varied in the countries of the West in both the form of the distinctive sign and the date of its application.> (col. 64)

Jewish marks in England: Badges and hats since 1215 - tabula since 1253

[since 1215: Strong regulations in England with the hat - rich Jews can ransom from the rules]

Jewish knob pointed hat, England, 13th century

<ENGLAND.

In England papal influence was at this time particularly strong. The recommendations of the Lateran Council were repeated in an order of March 30, 1218 [[and the Jewish hat was introduced]]. However, before long the wealthier Jews, and later on entire communities, paid to be exempted, notwithstanding the reiteration of the order by the diocesan council of Oxford in 1222.

[1253: Badge and tabula order]

In 1253, however, the obligation to wear the badge was renewed in the period of general reaction, by Henry III, who ordered the tabula to be worn in a prominent position.

[1275: Yellow badge order in tablet form]

In the statutum de Judeismo of 1275, Edward I stipulated the color of the badge and increased the size. A piece of yellow taffeta, six fingers long and three broad, was to be worn above the heart by every Jew over the age of seven years. In England, the badge took the form of the Tablets of the Law, considered to symbolize the Old Testament, in which form it is to be seen in various caricatures and portraits of medieval English Jews.> (col. 64)

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 63, a "Tablets of the Law" badge depicted in this English caricature of the Jew "Aaron son of the devil", dated 1277. Aaron is wearing the typical Jewish hood (cloth hat). London, Public Record Office.

Jewish marks in France: Yellow and red-white Badges

French Jewish badges and Jewish clothing in the Middle Ages.

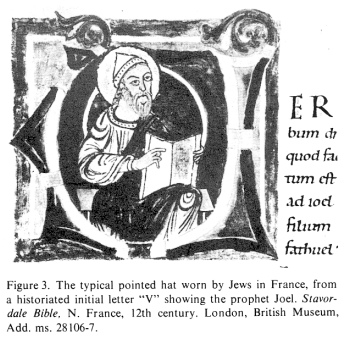

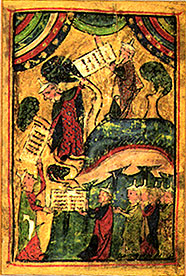

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 64: pointed Jewish hat, France, 12th century: This was the typical pointed hat worn by Jews in France, from a historiated initial letter "V" showing the prophet Joel. Stavordale Bible, N. France, 12th century. London, British Museum, Add. ms. 28106-7

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 65, French two colored red and white circular badge worn by French Jews in 13th and 14th century. A drawing after a French 14th century miniature. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale (National Library), ms. Français 820, fol. 192.

[1217: Order for a yellow round wheel badge - sabbath regulations - national badge edict 1269]

<FRANCE. In 1217, the papal legate in southern France ordered that the Jews should wear a rota ("wheel") on their outer garment but shortly afterward the order was rescinded. However, in 1219 King Philip Augustus ordered the Jews to wear the badge, apparently in the same form. Discussions regarding the permissibility of wearing the badge on the Sabbath when not attached to the garment are reported by *Isaac b. Moses of Vienna, author of the Or Zaru'a, who was in France about 1217-18.

Numerous church councils (Narbonne 1227, Rouen 1231, Arles 1234, Béziers 1246, Albi 1254, etc.) reiterated the instructions for wearing the badge, and a general edict for the whole of France was issued by Louis IX (Saint Louis) on June 19, 1269.

This edict was endorsed by Philip the Bold, Philip the Fair, Louis X, Philip V, and others, and by the councils of Pont-Audemer (1279), Nîmes (1284), etc.

[Badge variations: yellow or white and red - punishments when the badge is not worn]

The circular badge was normally to be worn on the breast; some regulations also required that a second sign should be worn on the back. At times, it was placed on the bonnet [[cap]], or at the level of the belt. The badge was yellow in color, or of two shades, white and red. Wearing it was compulsory from the age of either seven or thirteen years.

Any Jew found without the badge forfeited his garment to his denunciator. In cases of a second offense a severe fine was imposed.

When traveling, the Jew was exempted from wearing the badge. Philip the Fair extracted fiscal benefits from the compulsory wearing of the badge, by annual distribution of the badges by the royal tax collectors at a fixed price.> (col. 65)

Jewish marks in Spain: Badges and huts

Flavio Josefo / Flavius Josephus in a Spanish drawing from the Middle Ages with Jewish hat

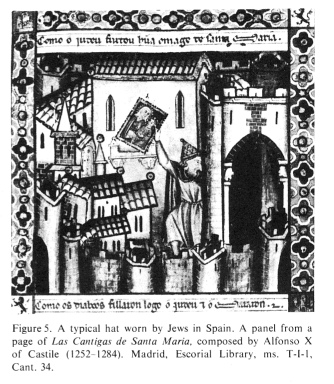

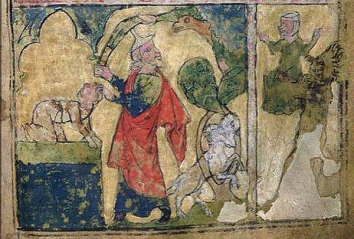

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 66, a typical hat worn by Jews in Spain. A panel from a page of Las Cantigas de Santa María, composed by Alfonso X of Castile (1252-1284). Madrid, Escorial Library, ms. T-I-I, Cant. 34.

[Badge regulations in Spain since 1215 - flight of some Jews to Muslim countries - badge regulations suspended - sporadic badge regulations]

<SPAIN. The obligation to wear the Badge of Shame was reenacted by the secular authorities in Spain shortly after the promulgation of the decrees of the Lateran Council, and in 1218 Pope Honorius III instructed the archbishop of Toledo to see that it was rigorously enforced. The Spanish Jews did not submit to this passively, and some of them (col. 65)

threatened to leave the country for the area under Muslim rule. In consequence, the pope authorized the enforcement of the regulation to be suspended. The obligation was indeed reenacted sporadically (e.g., in Aragon 1228, Navarre 1234, Portugal 1325).

[Jews with "influence" can arrange life without badge - Castile 1263: penal law under Alfonso X - Aragon 1268: no badge rule, but cape suggestion under James I]

However, it was not consistently enforced, and Jews who had influence at court would often secure special exemption. Alfonso X the Wise of Castile in his Siete Partidas [[seven charters]] (1263) imposed a fine or lashing as the penalty for a Jew who neglected the order. In 1268 James I of Aragon exempted the Jews from wearing the badge, requiring them on the other hand to wear a round cape (capa rotunda).

[Castile 1405: badge regulation - 1412: clothing and red badge law - and hair and beard law - Aragon 1393: clothing rule for Jews]

In Castile, Henry III (1390-1406) yielded in 1405 to the demand of the Cortes and required even his Jewish courtiers to wear the badge.

As a result of Vicente *Ferrer's agitation, the Jews were ordered in 1412 to wear distinctive clothing and a red badge, and they were further required to let their hair and beards grow long. The successors of Henry III renewed the (col. 66)

decrees concerning the badge.

In Aragon, John I, in 1393, prescribed special clothing for the Jews.

[Barcelona 1397: special terror against Jews with marks]

In 1397, Queen Maria (the consort of King Martin) ordered all the Jews in Barcelona, both residents and visitors, to wear on their chests a circular patch of yellow cloth, a span in diameter, with a red "bull's eye" in the center. They were to dress only in clothing of pale green color - as a sign of mourning for the ruin of their Temple, which they suffered because they had turned their backs upon Jesus - and their hats were to be high and wide with a short, wide cuculla. Violators were to be fined ten libras and stripped of their clothes wherever caught. When in 1400 King Martin granted the Jews of Lérida a charter of privileges, he required them, nevertheless, to wear the customary badge.

In 1474, the burghers of Cervera sought to impose upon the local Jews a round badge of other than the customary form. In the period before the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, the wearing of the Jewish badge was almost universally enforced, and some persons demanded that it should be extended also to Conversos.> (col. 67)

Jewish marks in Italy: Badges, hats and kerchieves - first ghetto in 1555

[Different rules in split Italy 1221-22: a blue "T" and beard law in Sicily - badge in Pisa]

<ITALY. Presumably the order of the Lateran Council was reenacted in Rome very soon after its promulgation in 1215, but it was certainly not consistently enforced. In 1221-22 (col. 67)

the "enlightened" emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen ordered all the Jews of the Kingdom of Sicily to wear a distinguishing badge of bluish color in the shape of the Greek letter T and also to grow beards in order to be more easily distinguishable from non-Jews. In the same year the badge was imposed in Pisa and probably elsewhere.

[since 1257: Papal States: circular yellow badge for Jews - two blue stripes on the veil for women Jews]

In the Papal States the obligation was first specifically imposed so far as is known by Alexander IV in 1257; there is extant a moving penitential poem written on this occasion by Benjamin b. Abraham *Anav expressing the passionate indignation of the Roman Jews on this occasion. The badge here took the form of a circular yellow patch a handspan in diameter to be worn on a prominent place on the outer garment: for the women, two blue stripes on the veil.

[since 1360: Rome: red cap for Jews - red apron for women Jews - and harsh control]

Red Jewish hat 01

Red Jewish hat 02

In 1360 an ordinance of the city of Rome required all male Jews, with the exception of physicians, to wear a coarse red cape, and all women to wear a red apron, and inspectors were appointed to enforce the regulation. Noncompliance was punished by a fine of 11 scudi; informers who pointed out offenders were entitled to half the fine. The ordinance was revised in 1402, eliminating the reward for informing, and exempting the Jews from wearing the special garb inside the ghetto [[since 1555]].

[Control in Sicily]

In Sicily, there was from an early period a custos rotulae whose function it was to ensure that the obligation was not neglected.

Elsewhere in Italy, however the enforcement was sporadic, although it was constantly being demanded by fanatical preachers and sometimes temporarily enacted.

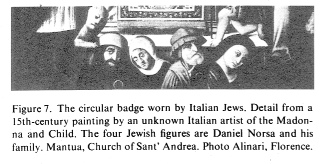

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 67, circular badge worn by Italian Jews. Detail from a 15th-century painting by an unknown Italian artist of the Madonna and Child. The four Jewish figures are Daniel Norsa and his family. Mantua, Church of Sant' Andrea. Photo Alinari, Florence.

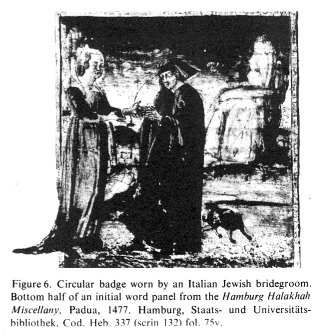

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 66, circular badge worn by an Italian Jewish bridegroom. Bottom half of an initial word panel from the "Hamburg Halakhah Miscellany", Padua, 1477. Hamburg, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek (Municipal and University library). Cod. Heb. 337 (scrin 132), fol. 75v.

[1555-1792: First ghetto system in the Papal States - with the badge]

The turning point came with the bull Cum nimis absurdum of Pope *Paul IV in 1555, which inaugurated the ghetto system. This enforced the wearing of the badge (called by the Italian Jews scimanno, from Heb. siman) for the Papal States, later to be imitated throughout Italy (except in Leghorn), and enforced until the period of the French Revolution [[in 1792]].

[Rome: yellow hats and yellow kerchieves - Venice: red hats and red kerchieves - Crete: badges on the shops - David d'Ascoli punished for resistance]

In Rome as well as in the Papal States in the sough of France, it took the form of a yellow hat for men, a yellow kerchief for women. In the Venetian dominions the color was red.

In Candia (Crete), the under Venetian rule, Jewish shops had to be distinguished by the badge.

David d'Ascoli, who published in 1559 a Latin protest against the degrading regulation, was severely punished and his work was destroyed.> (col. 68)

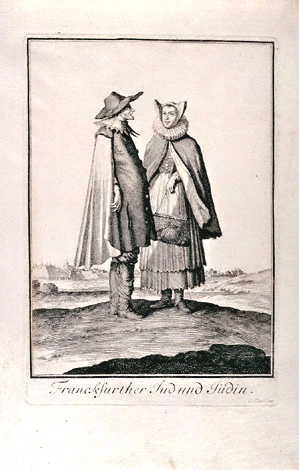

Jewish markings in Germany: Hats, badges, bells, veils, collars]

[Holy Roman Empire: The pointed hat]

German Jewish hats on the Naumburger Lettner in the Naumburg cathedral, 13th century

German Jewish hat of Nikodemus (right) with Jesus (left) on the baptismal font of Lippoldsberg (Lippoldsberger Taufstein) in the Lippoldsberg abbey church, 13th century

GERMANY. In Germany and the other lands of the Holy Roman Empire, the pointed hat was first in use as a distinctive sign. It was not officially imposed until the second half of the 13th century (Schwabenspiegel, art. 214, (col. 68)

c. 1275; Weichbild-Vulgata, art. 139, second half of 13th century; cf. Council of Breslau, 1267; Vienna, 1267; Olmuetz, 1342; Prague, 1355, etc.).

The church councils of Breslau and Vienna, both held in 1267, required the Jews of Silesia, Poland, and Ausdtria to wear not a badge but the pointed hat characteristic of Jewish garb (the pileum cornutum).

A church council held in Ofen (Budapest) in 1279 decreed that the Jews were to wear on the chest a round patch in the form of a wheel.

The badge was imposed for the first time in Augsburg in 1434, and its general enforcement was demanded by Nicolaus of *Cusa and John of *Capistrano. In 1530, the ordinance was applied to the (col. 69)

whole of Germany (Reichspolizeiordnung, art. 22). In the course of the 15th century, a Jewish badge, in addition to the Jewish hat, was introduced in various forms into Germany.

Jewish hats in a woodcut of Johannes Schnitzer of Armsheim: Five Jewish elders disputing, from the book: Seelen Wurzgarten, printed by Conrad Dinckmut, Ulm, 26 July 1483

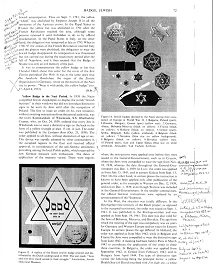

Jewish badge of the Middle Ages with inscription (pattern): "Der Juden Zeichen / Welches Sie ihren Kleidern zu tragen schuldig" ("The Jewish badge of guilt which is their tragedy to wear").

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol.4, col. 68, Jewish clothes with Jewish ring badges:

A German Jew and Jewess from Worms, 16th century, in typical Jewish dress

with circular badges on their garments. Worms, Stadtarchiv (municipal archive).

[1418: Salzburg: compulsary bells for the dresses of Jewish women]

A church council which met in Salzburg in 1418 ordered Jewish women to attach bells to their dresses so that their approach might be heard from a distance.

German Jewish hat on a statue of the portal of Maria Strassengel church near Judendorf in Steiermark (Austria)

[1434: Augsburg: yellow circles and yellow pointed veils]

In Augsburg in 1434 the Jewish men were ordered to attach yellow circles to their clothes, in front, and the women were ordered to wear yellow pointed veils.

[Nuremberg: Special visitor's hoods]

Jews on a visit to Nuremberg were required to wear a type of long, wide hood falling over the back, by which they would be distinguished from the local Jews.

[1530: general badge regulation in Germany - 1551: general badge regulation in Austria]

The obligation to wear the yellow badge was imposed upon all the Jews in Germany in 1530 and in Austria in 1551.

[Prague: yellow collars for Jewish women]

As late as in the reign of Maria Theresa (1740-80) the Jews of Prague were required to wear yellow collars over their coats.

Discontinuance.

[Medieval Yellow Jewish badges up to the French Revolution 1791]

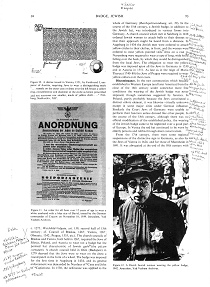

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Badge, vol. 4, col. 69, a decree issued in Vienna, 1551, by Ferdinand I, emperor of Austria, requiring Jews to wear a distinguishing mark "namely on the outer coat or dress over the left breast a yellow ring, circumference and diameter of the circle as herein prescribed and not narrower nor smaller, made of yellow cloth..." Freiburg, Stadtarchiv (municipal archive), XII°.

[Jewish regulations depending from region to region - almost no regulation in Poland]

In the new communities which became established in Western Europe (and later America) from the close of the 16th century under somewhat more free conditions the wearing of the Jewish badge was never imposed, though sometimes suggested by fanatics.

In Poland, partly probably because the Jews constituted a distinct ethnic element, it was likewise virtually unknown except in some major cities under German influence. Similarly the Court Jews of Germany were unable to perform their function unless dressed like other people.

[18th century: Jewish badge is neglected in big parts of Europe - Venice with red hats]

In the course of the 18th century, although there was no official modification of the established policy, the wearing of the Jewish badge came to be neglected over a good part of Europe. In Venice the red hat continued to be worn by elderly persons and rabbis through sheer conservatism.

From the 17th century, there were some regional suspensions of the distinctive sign in Germany, as also for the Jews of Vienna in 1624, and for those of Mannheim in 1691.

[Jewish emancipation and French revolution end of 18th century: all badge and hat laws are abrogated - Papal ghetto system abolished only in 1797]

It was abrogated at the end of the 18th centrury with (col. 70)

Jewish emancipation. Thus on Sept. 7, 1781, the yellow "wheel" was abolished by Emperor Joseph II in all the territories of the Austrian crown.

In the Papal States in France the yellow hat was abolished in 1791 after the French Revolution reached the area, although some persons retained it until forbidden to do so by official proclamation. In the Papal States in Italy, on the other hand, the obliagation was reimposed as late as 1793. When in 1796-97 the armies of the French Revolution entered Italy and the ghettos were abolished, the obligation to wear the Jewish badge disappeared.

Its reimposition was threatened but not carried out during the reactionary period after the fall of Napoelon, and it then seemed that the Badge of Shame was only an evil memory of the past.

[B. BL.] (col. 71)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

Bibliography

-- G. Rezasco: Segno degli ebrei (1889)

-- U. Robert: Signes d'Infamie ... (1891)

-- F. Singermann: Kennzeichnung der Juden im Mittelalter (1915)

-- Kisch, in: JH, 19 (1957), 89ff.

-- Lichtenstadter, in: JH, 5 (1943), 35ff.

-- Strauss, in: JSOS, 4 (1942), 59

-- A. Cohen: Anglo-Jewish Scrapbook (1943), 249-59

-- Aronstein, in: Zion, 13-14 (1948-49), 33ff.

-- B. Blumenkranz: Le Juif médiéval au miroir de l'art chrétien (1966)

-- S. Grayzel: Church and the Jews in the XIIIth Century (1966), index

-- Baron, Social, 11 (1967), 96-106

-- A. Rubens: History of Jewish Costume (1967), index.> (col. 73)

Picture credits

-- Jewish ball pointed hat 01: http://www.farbenundleben.de/kultur/trennfarben.htm

-- Jewish ball pointed hat 02: http://www.alainamiel.com/signedistinctifs/signesdistb.html

-- Jewish knob pointed hat, England, 13th century: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/heritage/episode4/presentations/4.3.6-1.html

-- French Jewish clothing: http://www.peti.pl/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_France;

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bd/FrenchJews1.jpg

-- Flavio Josefo / Flavius Josephus mit Judenhut: http://mural.uv.es/cruzague/losprotagonistasdemasada.htm

-- red Jewish hat 01: http://www.albert-ottenbacher.de/kaulbach/kau5.htm

-- red Jewish hat 02: http://www.albert-ottenbacher.de/kaulbach/kau5.htm

-- German Jewish hat, Regensburg Pentateuch 01, 1300 ca.: http://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje15/text17.htm; also in: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 4, col. 67

-- German Jewish hat, Regensburg Pentateuch 02, 1300 ca.: http://cja.huji.ac.il/Index_pres/00001.htm

-- Jewish woman with Jewish badge in yellow ring form, Worms 16th cent.:

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gelber_Ring; http://www.flholocaustmuseum.org; http://www.flholocaustmuseum.org/history_wing/assets/room1/jewish%20woman%20with%20yellow%20badge.jpg; also in: also in: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 4, col. 68

-- Jew with Jewish badge in yellow ring form, Worms 16th cent.:

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gelber_Ring; also in: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 4, col. 68

-- Jewish hat at the portal of the church Maria Strassengel near Judendorf in the Steiermark (Austria): http://www.albert-ottenbacher.de/kaulbach/kau5.htm

-- Jewish hat at the Naumburger Lettner: http://www.albert-ottenbacher.de/kaulbach/kau5.htm

-- Jewish hats in a woodcut of Johannes Schnitzer of Armsheim: Five Jewish elders disputing, from the book: Seelen Wurzgarten, printed by Conrad Dinckmut, Ulm, 26 July 1483: http://www.jtsa.edu/prebuilt/exhib/costume/4.html

-- a ring on the coat as Jewish sign, Frankfurt fair leaflet: http://www.juedischesmuseum.de/judengasse/dhtml/Z248.htm

-- German Jewish clothing, Frankfurt 1703: http://www.jtsa.edu/prebuilt/exhib/costume/5.html

-- German Jewish hat of Nikodemus on the Lippoldsberger taufstein:

http://www.klosterkirche.de/zeiten/trinitatis/10-trinitatis.php

^