<MOSCOW, (Rus.

Moskva), capital of the U.S.S.R. and from the Middle Ages

the political, economic, and commercial center of *Russia.

[Some Jews in Moscow up to

the 18th century - general prohibition to settle in

Moscow]

Up to the end of the 18th century, Jews were forbidden to

reside in Moscow although (col. 359)

[[The criminal orthodox "Christians" Church was the driving

force against the Jews but is never mentioned in the

article]].

many Jewish merchants from Poland and Lithuania visited the

city. In 1676 Jews who brought their wares to Moscow were

expelled. Apostates and forced converts who maintained

varying degrees of connection with Judaism and the Jews were

to be found in Moscow during various periods. A few Jews

among the prisoners brought to Moscow after the wars against

Poland apostatized and settle there. A physician of Jewish

origin, Daniel Gordon, was employed by the court in Moscow

from 1657 to 1687; Peter Shafirov, one of the most important

advisers of Czar Peter the Great, was also of Jewish origin.

[Belarus Jews from Shklov

in Moscow since 1772 - only temporary stay permitted since

1791]

With the Russian annexation of Belorussia (1772), the number

of Jewish merchants living in Moscow for commercial reasons

increased; they came in particular from *Shklov, then an

important commercial center in Belorussia. One of these was

the contractor and merchant Nathan Note *Notkin.

In 1790 Moscow merchants requested that the presence and

commercial activities of the Jews in the city be prohibited.

A royal decree forbidding Jewish merchants to settle in the

inner districts of Russia was issued in 1791. However, they

were authorized to stay for temporary periods in Moscow to

carry on their trade. Most of the Jews who came to Moscow

lodged at the Glebovskoye podvorye, an inn which was

situated in the center of the market quarter.

[Jewish merchants between

Moscow and the West and the South - Jewish export trade]

Jewish merchants continued to play an important role in the

trade between Moscow and the southern and western regions of

Russia, as well as in the export of Moscow's goods, and in

1828 the turnover of this trade was estimated at 27,000,000

rubles. As a result, Russian industrialists in Moscow

supported the rights of (col. 360)

the Jews.

[Guild Jews with the right

to remain one month in Moscow since 1828 - Glebovskoye inn

- prolonged stay of six months]

In 1828 Jewish merchants who were members of the first and

second guilds were authorized to remain in Moscow on

business for a period of one month only. They were forbidden

to open shops or to engage in trade within the city

boundaries. To facilitate the execution of these

regulations, the Jews were compelled to lodge solely in the

Glebovskoye podvorye. The inn was a charitable trust which

had been handed over to the Moscow city council to use its

income for the maintenance of a municipal eye clinic.

Exorbitant prices were soon extorted from Jewish merchants

who had to stay at the inn.

After a few years, third-class merchants were also

authorized to enter the town under the same conditions and

the period of their stay was prolonged to six months. About

250 people made use of this right every year. As a result of

these restrictions Jewish trade decreased to about

12,000,000 rubles annually during subsequent years.

[Temporary residence in

whole Moscow for Jews since 1855]

When Alexander II came to the throne (1855), Jewish

merchants were permitted to reside temporarily in all the

sections of the town.

[Permanent settlement of

Jewish Cantonists - professions and careers]

The first Jews to settle permanently in Moscow, and the

founders of the community, were *Cantonists who had finished

military service, some of whom had married Jewish women from

the *Pale of Settlement. In 1858 there were 340 Jewish men

and 104 Jewish women in the whole of the district of Moscow.

After Jewish merchants of the first guild, university

graduates, and craftsmen were allowed to settle in the

interior of Russia, the number of Jews increased rapidly.

Some were extremely wealthy, such as Eliezer *Polyakov, one

of the most important bankers in Russia and head of the

community, and K.Z. *Wissotzki.

From 1865 to 1884 Hayyim (Ḥayyim) Berlin officiated as rabbi

of Moscow, and in 1869 the community invited S.Z. *Minor,

one of the outstanding students of the Vilna rabbinical

seminary, to serve as the

*kazyonny

ravvin (government-appointed rabbi).

[Numbers 1871-1890 -

liberal governor of Moscow, Prince Dolgorukov]

There was an estimated Jewish population of 8,000 in the

city in 1871, which had grown to around 12,000 in 1882 and

35,000 (over 3% of the total population) in 1890, just

before the expulsion.

The governor of Moscow, Prince Dolgorukov, was known for his

liberal attitude toward the Jews, and (after receiving

bribes and gifts) the local administration overlooked their

illegal presence (as in the case of fictive craftsmen). A

considerable number of industrialists and merchants

recognized the advantages deriving from Jewish presence in

the city, and in a memorandum addressed to the minister of

finance in 1882 they pointed out their great contribution to

the city's prosperity.

While anti-Jewish persecutions and decrees were gaining

momentum throughout Russia after the accession of Alexander

III, a period of relative ease, the legacy of the previous

czar, continued in Moscow. This situation (col. 363)

changed completely with the deposition of Prince Dolgorukov

and the appointment of Grand Prince Sergei Alexandrovich as

governor of the city. During the 14 years (1891-1905) of his

term in office, his main aim was "to protect Moscow from

Jewry".

The Expulsion.

[The expulsion decree of

the Jews of Moscow in 1891 under Grand Prince Sergei

Alexandrovich - expulsion of about 30,000 Jews in 1892 -

flight to Warsaw and Lodz]

On March 28, 1891 (Passover Eve 5651), a law was issued

abolishing the right of Jewish craftsmen to reside in Moscow

and prohibiting their entry into the city in the future. The

police immediately began to expel thousands of families,

some of whom had lived in Moscow for several decades or were

even born there. They were granted a period of from three

months to a year to dispose of their property and many were

compelled to sell out to their neighbors at derisory prices.

The poor and destitute were sent to the Pale of Settlement

with criminal transports. On October 15 the right of

descendants of the Cantonists to live in the town was

abrogated, if they were not registered with the Moscow

community. The expulsion reached its climax during the cold

winter days of 1892. While the police made a concerted

effort to search out the Jews and drive them out of the

city, generous rewards were offered for the seizure of any

still in hiding.

The press was not permitted to report on the details of the

expulsion. An appeal to the government made by merchants and

industrialists in 1892 and their warning of the economic

damage that would result from the expulsion were of no

avail. Police sources estimated that about 30,000 persons

were expelled. About 5,000 Jews remained - families of some

Cantonists, wealthy merchants and their servants, and

members of the liberal professions.

[[As it seems the brutal police force is collaborating

willingly and makes career with the expulsion of the Jews.

And the criminal Orthodox "Christian" Church is never

mentioned in the article]].

The Moscow expulsion came as a deep shock to Russian Jewry.

A considerable number of those expelled arrived in Warsaw

and Lodz and transferred their economic activities there.

[[...]]

In 1893 J. *Mazeh was elected as rabbi of Moscow, remaining

its spiritual leader until his death in 1923. [[...]] In

1897 there were 8,095 Jews and 216 Karaites in Moscow (0.8%

of the total population). [[...]]

[More restrictions for the

staying bout 5,000 Jews]

Decrees regulating residence in Moscow became even more

severe. In 1899 the authorities ordered that no more Jewish

merchants were to be registered in the first guild unless

authorized by the minister of finance. At the height of the

expulsion period, the authorities closed down the new

synagogue, as well as nine of the 14 prayer houses. Rabbi

S.Z. Minor, who requested the reopening of the synagogue,

was expelled from the city. The struggle for the use of the

synagogue continued for many years and it was not until 1906

that permission was granted for its reopening. [[...]]

In 1902 there were 9,339 Jews there, and half of them

declared Yiddish as their mother tongue; the overwhelming

majority of the others declared it to be Russian. [[...]]

A considerable

number of the members of the small community were wealthy

merchants and intellectuals. Assimilated Jews (some of whom

apostatized) held an important place in the cultural life of

the city. In 1911 there were around 700 Jewish students in

the higher institutions of learning in Moscow.

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Moscow, vol. 12, col. 359-360. Twenty-fifth

anniversary meeting in Moscow of the early [[racist]]

Zionist group, Benei Zion, 1909. The photograph

includes: 1. Jehiel Joseph Levontin, 2. Jacob Mazeh,

3. Jehiel Tschlenow, 4. Pesah Marek, 5. Isaac

Naiditsch, 6. Eliezer Tcherikower. Jerusalem,

J.N.U.L., Schwadron Collection Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 359-360. Twenty-fifth anniversary meeting in

Moscow of the early [[racist]] Zionist group, Benei

Zion, 1909. The photograph includes: 1. Jehiel Joseph

Levontin, 2. Jacob Mazeh, 3. Jehiel Tschlenow, 4.

Pesah Marek, 5. Isaac Naiditsch, 6. Eliezer

Tcherikower. Jerusalem, J.N.U.L., Schwadron

Collection](EncJud_Moskau-d/EncJud_Moscow-band12-kolonne359-360-rass-zionisten1909-33pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

(1971): Moscow, vol. 12, col. 359-360. Twenty-fifth

anniversary meeting in Moscow of the early [[racist]]

Zionist group, Benei Zion, 1909. The photograph

includes: 1. Jehiel Joseph Levontin, 2. Jacob Mazeh, 3.

Jehiel Tschlenow, 4. Pesah Marek, 5. Isaac Naiditsch, 6.

Eliezer Tcherikower. Jerusalem, J.N.U.L., Schwadron

Collection

After the outbreak of World War I, from 1915, a stream of

Jewish refugees began to arrive in Moscow from the

German-occupied regions. They took part in the development

of war industries in the town and some of them amassed large

fortunes. In a short time, Moscow became a Jewish center.

[[The Jewish refugees were expelled by the Russian army from

the frontier districts, see *

Lithuania,

*

Latvia,

and *

Estonia]].

Hebrew printing presses were set up, and in the town of

Bogorodsk (near Moscow) a large yeshivah [[religious Torah

school]] was established on the pattern of the Lithuanian

yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]]. Thee foundations of

the Hebrew theater *Habimah were then laid. Among the new

rich were [[racist]] Zionists and nationally conscious Jews

who were ready to support every cultural activity. Most

outstanding of these were H. *Zlatopolsky, his son-in-law Y.

Persitz, and A.J. *Stybel. Authorization was given for the

publication of a Hebrew weekly,

Ha-Am.

[February revolution of

1917]

Cultural activity increased in scope with the outbreak of

the (col. 364)

February 1917 Revolution. It was symbolical that O. *Minor,

the son of S.Z. Minor, a leader of the Social Revolutionary

Party, was elected as chairman of the Moscow municipal

council. [[...]]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12, col. 362.

Last issue of the Moscow Hebrew newspaper, Ha-Am, November

23, 1917. The lead articleis on the Balfour Declaration.

Jerusalem, Central Zionist Archives.

When Moscow became the capital of the Soviet Union, its

Jewish population rapidly increased. In 1920 there were

28,000 Jews in the city, which had become severely

depopulated as a result of the civil war. By 1923 the number

had increased to 86,000 and by 1926 to 131,000 (6.5% of the

total population). [[...]]

[More Jewish cultural

activities in Moscow - 400,000 Jews estimated in 1940]

Ha-Am became a daily newspaper and two large

publishing houses, Ommanut (founded by Zlatopolsky and

Persitz) and that of A.J. Stybel, were set up. The founding

conference of the organization for Hebrew education and

culture, *Tarbut, was held in Moscow in the spring of 1917.

This activity also continued during the first year of the

Bolshevik Revolution (three volumes of

Ha-Tekufah were

published in 1918, as well as others) but the new regime,

with the assistance of its Jewish supporters, rapidly

liquidated the institutions of Hebrew culture in Moscow.

The Habimah theater was more fortunate; it presented

An-Ski's

Dibbuk (Dybbuk)

in Moscow for the first time in January 1922 and continued

to exist under the protection of several prominent members

of the Russian artistic and literary world who defended it

as a first class artistic institution, until it left the

Soviet Union in 1926. [[...]]

[[The Communist terror against the merchants and the NEP

policy are not mentioned in this article, see: *

Soviet

Union. The Gulag system and forced labor system in

"Soviet Union" with the construction of long railroad lines

or canals accompanied by mass death by freezing or hunger

etc. are never mentioned in Encyclopaedia Judaica]].

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12, col.

361-362. The Moscow Jewish State Theater in a

production of "King Lear" with S. Mikhoels in the title

role, 1935. Courtesy C.A.H.J.P., Jerusalem.

In 1940 the Jewish population was estimated at 400,000. the

headquarters of the *Yevsektsiya was situated in Moscow, and

there its central newspaper

Der Emes (1920-38) was published as well

as many other Yiddish newspapers and books. The Jewish State

Theater (known in Russian as GOSET from its initials),

directed by S. *Mikhoels, was also situated in Moscow. For a

number of years, small circles of organized [[racist]]

Zionists continued to exist in the city, which was the

central seat of the legal *He-Halutz (He-Ḥalutz) (which

published its own newspaper from 1924 to 1926) and of the

groups of the Left *Po'alei Zion. All these were liquidated

by 1928.

[World War II -

Anti-Fascist Committee and newspaper "Eynikeyt"]

During World War II, the Jews shared the sufferings of the

war with the city's other inhabitants. From 1943 Moscow was

seat of the Jewish *Anti-Fascist Committee which gathered

together personalities of Jewish origin who were outstanding

in Soviet public affairs. Founded to assist the Soviet Union

in its war effort against Nazi Germany and to mobilize world

Jewish opinion and aid for this purpose, it published a

newspaper, Eynikeyt [[Yidd.: "Unity"]].

[Y.S.]

[[The Big Flight from Barbarossa, the circumstances in the

hard winters and the defense battles before Moscow are not

mentioned]].

After World War II.

[Destruction of the Jewish communities since 1948]

The Anti-Fascist Committee attempted to continue with its

activities even after the war until it was brutally

liquidated in 1948-49, as a first step in the total

liquidation of organized Jewish life in the "black years" of

Stalin's regime.

[[Since 1948 - since the foundation of a racist Zionist Free

Mason CIA Herzl Israel - Stalin's anger was headed against

the Jews in general, because the new "Jewish State of

Israel" - with the aim of borderlines at the Nile and at the

Euphrates (according to 1st Mose, chapter 15, phrase 18) -

was collaborating with the criminal "USA" and it's secret

service CIA. By this Stalin and his government felt

encircled by the Western powers, and corresponding measures

were taken to destroy any Western structure in the Soviet

Union, so, also all Jewish life. And the "Soviet Union" was

supporting all Arab states against racist Zionist

imperialism. By all this there was born the eternal war in

the Middle East. Stalin's regime wanted to have Israel as a

Communist satellite on the Mediterranean Sea...]]

Most of its [[the Anti-Fascist Committee's]] leading members

were arrested and executed in 1952.

[Representatives from

racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel in Moscow -

demonstrations]

Because Moscow is the capital and a "window" of the Soviet

Union, it has been (col. 365)

possible for world Jewry to follow the destinies of Moscow's

Jews more than those in other cities and the latter have

been more able to meet with Jews from outside the Soviet

Union. When Golda *Meir, the first diplomatic representative

of the [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] State of

Israel, arrived in Moscow in September 1948, a spontaneous

mass demonstration of Jews in her honor took place on the

High Holidays near and around the Great Synagogue. The mere

presence of an Israel diplomatic mission with an Israel flag

in the center of Moscow was a constant stimulus to Jewish

and pro-Israel sentiments among the Jews of Moscow and

Jewish visitors from other parts of the Soviet Union.

The Israel delegation to the Youth Festival, held in Moscow

in 1957, was the first occasion of personal contacts between

Jewish youth from [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]]

Israel and the U.S.S.R. It is considered to have been a

turning point in the revival of Jewish national feelings and

their daring demonstration in public on the part of Soviet

Jewish youth.

Already in 1958, on *Simhat (Simḥat) Torah eve more than

10,000 young Jews gathered around the Great Synagogue to

dance and sing Yiddish and Hebrew songs. They refused to be

intimidated by the militia and to disperse. Thus these mass

gatherings of young Jews, which also take place on their

Jewish holidays, became a traditional feature of Jewish life

in Moscow.

In 1955 some elderly Jews were tried and sentenced to

several years of imprisonment in labor camps for possessing

and distributing Israel newspapers and Hebrew literature and

gathering in groups to read them. For similar "offenses"

several Jews of the Great Synagogue congregation were

punished in 1963. (col. 366) [[...]]

From 1961 a barrier was erected in the Great Synagogue to

separate foreign visitors, including Israel diplomats, from

the congregation, and the synagogue officers were

responsible to the authorities for strictly enforcing the

segregation. (col. 367) [[...]]

[Numbers]

In the census of 1959, 239,246 Jews (4.7% of the total

population) were registered in the municipal area of Moscow.

Of these, 132,223 were women and 107,023 were men. 20,331 of

them (about 8.5%) declared Yiddish to be their mother

tongue. These numbers are thought to be a gross

underestimate because many tens of thousands of Jews

declared at the census their "nationality" to be Russian

(some opinions evaluate the number of Moscow's Jews as high

as 500,000). (col. 368)

[Pogrom of 1959: fire in

the synagogue - murder of the shammash - graffiti]

In 1959, on Rosh Ha-Shanah eve, an anti-Jewish riot took

place in Malakhovka, a suburb of Moscow. The synagogue was

set afire, but quickly extinguished; the

shammash [[salaried

servant in a synagogue]] of the Jewish cemetery was murdered

by unknown persons and on the walls a typewritten

anti-Semitic tract appeared, signed by "the B.Zh.S.R.

Committee", the Russian initials of the prerevolutionary

anti-Semitic slogan "Hit the Yids and save Russia".

At first Soviet spokesmen denied the facts, but several

months later admitted them to foreign visitors, assuring

them that the hooligans were apprehended and severely

punished. The Soviet press did not mention the incident at

all.

[[It can be admitted that there were many more pogroms]].

[Jewish cemetery

discontinued since 1960 - economic trials]

In 1960 a stir was created among Moscow Jewry when burying

at the Jewish cemetery was almost discontinued and Jews were

forced to bury their dead in a separate section of a general

cemetery. This section was filled up in 1963 and subsequent

Jewish burials had to take (col. 367)

place alongside non-Jewish ones. Some Jews in various ways

obtained the privilege of burying their dead in the

remaining space of the old Jewish cemetery, others carried

them to the Jewish cemetery of Malakhovka.

At the same period several Jews in Moscow were accused,

tried, and sentenced to the severest punishment, including

execution, for "economic crimes", such as speculation,

organizing illicit production and sale of consumer goods in

collusion with high officials of the militia, directors of

factories, etc. Their trials were accompanied by

inflammatory feature articles (called "feuilletons") in the

central Moscow press with pronounced anti-Semitic overtones.

[[After every war in the Middle East with a winner named

"Israel" (racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel) there

was a new anti-Semitic propaganda wave, with the destruction

of cemeteries step by step, of synagogues, and with new

discrimination laws]].

[Yiddish culture in Moscow:

Yiddish newspapers and writers]

However, Moscow was also the center of other developments.

IN 1959 some Yiddish books, most of them selective works of

the classics (*Shalom Aleichem, I.L. *Peretz, D. *Bergelson,

etc.), were published there after a prolonged period of the

complete obliteration of any printed Yiddish word. Yiddish

folklore concerts took place relatively frequently in the

city and drew large crowds. Even a semiprofessional theater

troupe, headed by the elderly actor Benjamin Schwartzer, was

established and mainly performed Shalom Aleichem plays in

provincial cities. In 1961 the Yiddish journal

*Sovetish Heymland

[[Soviet Homeland]] edited by an officially appointed

editor, the poet Aaron *Vergelis, began to appear as an

"organ of the Soviet Writers' Union", first as a bimonthly,

later as a monthly. It also served as a kind of

Soviet-Jewish mouthpiece for foreign Jews and visiting

Jewish intellectuals were invited to its premises to meet

members of its editorial staff. In 1963 and 1965 collections

of Israel Hebrew poetry and prose were published in Russian

translation, as well as a Hebrew-Russian dictionary in 1965

(in 25,000 copies), which was sold out in a few weeks.

[Cultural life - Rabbi

Schliefer, a pacifist rabbi with revised Jewish prayer

book without wars]

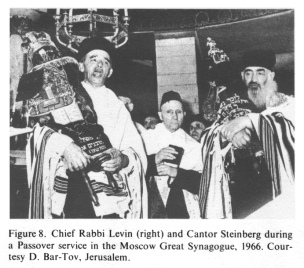

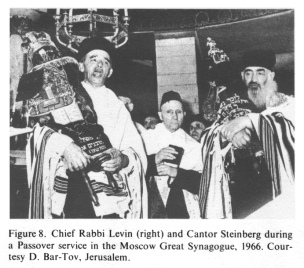

The Great Synagogue and its rabbi (first S. *Schliefer and

after his death J. L. *Levin) serve the authorities often as

unofficial representatives of Soviet Jewry to the outside

world.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12, col. 367.

Chief Rabbi Levin (right) and Cantor Steinberg during a

Passover service in the Moscow Great Synagogue, 1966.

Courtesy D. Bar-Tov, Jerusalem.

In the 1950s and 1960s the Great Synagogue was allowed to

issue a Jewish calendar and to sent it to other synagogues

in the U.S.S.R. In 1956 Rabbi Schliefer was granted

permission to print a prayer book, by photostat from old

prayer books. He named it

Siddur

ha-Shalom ("peace prayer book") and deleted from it

all references to wars and victories (as, e.g., in the

Hanukkah (Ḥanukkah) benedictions). It was said to have been

printed in 3,000 copies, but it was very rarely seen in

other synagogues in the Soviet Union. (A second edition of

it was printed, ostensibly in 10,000 copies, in 1968 by

Rabbi (col. 366)

Levin, but it also was not much in use in Soviet

synagogues).

[The religious Torah school

of the pacifist rabbi Schliefer since 1957]

In 1957 Rabbi Schliefer received permission from the

authorities to open a yeshivah [[religious Torah school]] on

the premises of the Great Synagogue. He called it "Kol

Ya'akov", and for several years a small number of young and

middle-aged Jews (bout 12 persons a year), mostly from

Georgia, were trained there, almost all of them as

*shohatim (shoḥatim)

(ritual slaughterers), whereas the number of ordained rabbis

did not exceed one or two. In 1961 the yeshivah, though

officially still in existence, almost ceased to function,

mainly because of the refusal of the Soviet authorities to

grant permission to yeshivah students, who went for the

holiday to their homes outside Moscow, to come back and

register again as temporary residents of the city for the

purpose of study. By 1963, 37 students had passed through

the yeshivah; 25 of them were trained as

shohatim (shoḥatim). In

1965 only one student was there, and in 1966 the number was

six.

[Unleavened bread - ritual

slaughtering]

The unrestricted baking of

mazzah (maẓẓah) [unleavened bread]] in a

rented bakery and its distribution in food stores was

discontinued in Moscow, as in most areas of the Soviet

Union, in 1962. However, it was partially permitted again in

1964 and definitely in 1965, but under a different system:

it was done under the supervision of the synagogue board and

was only for "believers" who brought their own flour and

registered their names.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12, col. 365.

Baking mazzah in Moscow.

The ritual slaughtering of poultry was allowed in the

precincts of the Great Synagogue whereas kosher beef was

obtainable until 1964 twice a week at a special store on the

outskirts of the city. (col. 367) [[...]]

[1970]

In 1970 three synagogues were functioning in the city of

Moscow. Apart from the Great Synagogue on Arkhipova Street,

there were two small synagogues - in the suburbs of Maryina

Roshcha and Cherkizovo, which were wooden buildings, more of

the type of a

shtibl

[[small room]] than of a full-fledged synagogue. In addition

to them, there was a synagogue in the nearby town of

Malakhovka, practically also a suburb of Greater Moscow,

which has had a sizable Jewish population from

prerevolutionary times. (col. 366)

[Contacts with racist

Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel]

Contacts with Israel took manifold forms. The Israel embassy

invited to its receptions not only the rabbis and board

members of the various synagogues, but also Jewish writers,

artists, and other intellectuals. In various sport events,

international scientific congresses, and international

exhibitions [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel

was almost always represented, and often not only Moscow

Jews but also Jews from other parts of the Soviet Union,

even from outlying regions, came especially to the capital

"to see the Israelis". From time to time Israel popular

singers (e.g., Nechama Hendel, Geulah Gil, etc.) and other

artists performed in Moscow and aroused great enthusiasm,

particularly among young Jews.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12, col. 361.

The Israel Embassy in Moscow, prior to June 1967

The Six-Day War and the rupture of diplomatic relations

between the Soviet Union and [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA

Herzl]] Israel (June 1967) put an end to these contacts.

[[The Six-Day War was a national climax for the Jewish

racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl government, and racist

members of the government said the new occupations were a

step forward to a "Greater Israel", e.g. Moshe Dayan.

Palestinians were treated like pigs]].

But, on the other hand, many Moscow Jews, especially the

young, began more and more openly to demonstrate their

pro-Israel feelings - by continuing increasingly their mass

gatherings around the Great Synagogue, by signing collective

protests against the refusal to grant them exit permits to

[[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel, by studying

Hebrew in small groups, etc. Unlike other cities, like

*Riga, *Leningrad, *Kishinev, and some towns in *Georgia,

there were hardly any sanctions applied in Moscow in 1970

against pro-Israel Jews. [[...]]

[ED.]> (col. 368)

| Sources |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 359-360

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 363-364

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 365-366

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 367-368

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 363. Israel national basketball team at the

opening in Moscow of the Eighth European

Basketball Championship games, 1953. Photo Baruch

Bagg, Tel Aviv

|

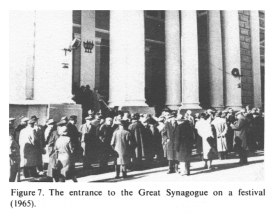

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 366. The entrance to the Great Synagogue on a

festival (1965)

|

|

|

|

|

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Moscow, vol. 12, col. 359-360. Twenty-fifth

anniversary meeting in Moscow of the early [[racist]]

Zionist group, Benei Zion, 1909. The photograph

includes: 1. Jehiel Joseph Levontin, 2. Jacob Mazeh,

3. Jehiel Tschlenow, 4. Pesah Marek, 5. Isaac

Naiditsch, 6. Eliezer Tcherikower. Jerusalem,

J.N.U.L., Schwadron Collection Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Moscow, vol. 12,

col. 359-360. Twenty-fifth anniversary meeting in

Moscow of the early [[racist]] Zionist group, Benei

Zion, 1909. The photograph includes: 1. Jehiel Joseph

Levontin, 2. Jacob Mazeh, 3. Jehiel Tschlenow, 4.

Pesah Marek, 5. Isaac Naiditsch, 6. Eliezer

Tcherikower. Jerusalem, J.N.U.L., Schwadron

Collection](EncJud_Moskau-d/EncJud_Moscow-band12-kolonne359-360-rass-zionisten1909-33pr.jpg)