index next

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971

Jews in "Soviet Union" 01: Communist terror and Yiddish culture

Split Jewry within new borderlines - the "nation" question - Red Army advancement - discriminated former bourgeoisie and poor Jewish masses - Jewish sections "Yevsektsiya" - destruction of religion - Jewish Yiddish culture - Russian school system and mixed marriages for assimilation

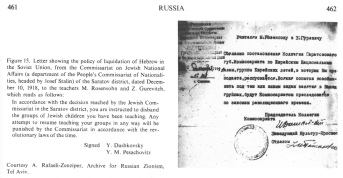

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 461-462, public prohibiton of

yeshivot schools [[religious Torah schools]] in Izvestia, 19 June 1919

from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 14

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter |

|

|

|

<Under the Soviet Regime. [The new borderlines]

[[Gulag system and forced labor system in "Soviet Union" with the construction of long railroad lines or canals accompanied by mass death by freezing or hunger etc. are never mentioned in Encyclopaedia Judaica]].

By 1920 the borders of Soviet Russia took shape. A considerable number of Jews who had formerly been included within the borders of the Russian Empire remained in the states which had broken away from it (Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Bessarabia, incorporated into Rumania [[Romania]]).

About 2,500,000 Jews only remained within the limits of Soviet Russia. The fate of the Jews within the borders of Soviet Russia was to a large extent determined by the theory and practice of the Communist Party. Its outlook defined and crystallized during the 20 years which preceded the Revolution. Like all (col. 459)

the other socialist and liberal parties, the Bolshevik party repudiated anti-Semitism, while the civic emancipation of the Jews, as that of the other Russian peoples, formed part of its program. It took some time until the party recognized Jews as a nationality. Under the influence of assimilated Jews, who carried weight in the circles of the socialist leadership of Europe and Russia, the Bolsheviks were inclined to regard integration and assimilation as the only "progressive" solution of the Jewish problem. This outlook was sharpened during the bitter discussion at the beginning of the century between the Bolsheviks and the Bund.

Leaning upon Marx, K. Kautsky, and O. *Bauer, Lenin declared that "there is no basis for a separate Jewish nation", and in regard to a

"national Jewish culture - the slogan of the rabbis and the bourgeoisie - this is the slogan of our enemies".

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 461-462,

pink slip with the dismissal for two teachers, 10 December 1918

[Stalin's definition of a "nation" - Jews are a "nation on paper" - assimilation is wanted - Jews in the Red Army]

Stalin declared in his pamphlet Marksizm i natsionalny vopros ("Marxism and the National Question", 1913) that a nation is a "stable community of men, which came into being by historic process and has developed on a basis of common language, territory, and economic life"; since the Jews lack this common basis they are only a "nation on paper", and the evolution of human society must necessarily lead toward their assimilation within the surrounding nations.

These theories of the fathers of Communism increasingly influenced Soviet policy toward the Jews, though in the beginning the Soviets were compelled by the actual conditions to deviate from their theories and to allow the existence of Jewish political and cultural institutions (the *Yevsektsiya (see below); Yiddish schools and publications, etc.). These deviations, however, proved in the long run to be of a temporary character, after which the line - of imposed assimilation of the Jews - was implemented with even more energy and firmness.

[[There is the big error that Jews are not a nation but a religion, and a religion can never be a nation. Add to this many "American" Jewish organizations also said that Jews are a religion and assimilation was better than nationalism]].

By its war on anti-Semitism and pogroms, the new regime gained the sympathy of the Jewish masses whose lives depended on its victory. [...] In the Soviet air force there was General Y. *Shmushkevich. In 1926, 4.4% of the officers of the Red Army were Jews (two-and-a-half times higher than their ratio to the general population). Jews took an important part in the restoration of the country's administration which had collapsed after a large section of the Russian intelligentsia and former officialdom emigrated from Soviet Russia or refused to serve in it.

[Impoverished Jewish masses of the bourgeoisie by nationalization of all property - mass flight to east European countries - NEP]

However, the new regime brought complete economic ruin to the Jewish masses, most of whom belonged to the "petty bourgeoisie" of the towns and townlets. The abrogation [[abolition]] of private commerce, confiscation of property and goods, and liquidation of the status of the townlet as the intermediary between the peasants and the large towns - all these deprived hundreds of thousands of Jewish families of their livelihoods.

About 300,000 Jews succeeded in leaving the Soviet-controlled territories for Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, and Rumania [[Romania]]. The declaration of Lenin on the failure of the economic policy of the period of "war Communism", the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP), together with the conclusion of the civil war and the restoration of order in the country, brought some relief to the Jews, but their economic situation was broken and hopeless.

With economic ruin, the new regime also brought (col. 460)

spiritual ruin to the Jews. When the Bolsheviks seized power, they were compelled to recognize the fact, even if as a temporary phenomenon, of the existence of millions of Jews who were attached to their language and their national tradition. [[This is a religious tradition]]. A Jewish commissariat headed by the veteran Bolshevik S. *Dimanstein was established between 1918 and 1923 to deal with Jewish affairs.

[Jewish sections in political life of "Soviet Union" - Yiddish culture against Hebrew culture]

"Jewish Sections" (Yevsektsiya) were also set up in the branches of the Communist Party. Jewish members of the party who were prepared to work among their fellow Jews were organized in these sections. The function of the Yevsektsiya was to "impose the proletarian dictatorship among the Jewish masses".

The older Jewish members of the Communist Party were mostly assimilationists who did not want any contact with their people. However, as the success of the Bolsheviks and the efficiency of their terror measures became increasingly evident, they were joined by sections of Jewish socialist parties (the Bund, the *United Jewish Socialist Workers' Party, the *Po'alei Zion) as well as by individual Jews. These brought with them ideas on the fostering [[setting up]] of a secular Jewish culture in Yiddish and envenomed [[poisoned]] hatred toward the Jewish religion, the Hebrew language, the Bible, and the [[racist]] Zionist movement.

The Communist Party put them in control of the Jewish population centers, at the same time stressing that their activity was only a temporary measure for as long as it would be required.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 465-466, play Habimah in Moscow 1922

[Yevsektsiya activities: destruction of Jewish institutions - synagogues as workshops - underground institutions - prohibition of Hebrew activities]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 469, emblem of Belarus with Yiddish inscription

The first activity of the Yevsektsiya was the liquidation of the religious and national organization of the Jews of Russia. In August 1919 the Jewish communities were dissolved and their properties confiscated. The general anti-religious policy took the form, in relation to the Jews, of persecution of traditional Jewish culture and education, of prohibiting the religious instruction of children, the closure of hadarim [[small Jewish schools]] and yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]], and the seizure of synagogues which were converted into clubs, workshops, or warehouses.

[[The same dissolution and nationalization happened with the institutions of criminal anti-Semitic Orthodox church]].

A violent campaign against the Jewish religion and its leaders was conducted and heavy taxes were imposed on the rabbis and other religious officials in order to compel them to resign from their positions. In these activities the Yevsektsiya encountered the opposition of the religious masses, who based themselves on the promise of freedom of religious worship, which was officially proclaimed and later included in the Soviet constitution, and struggled for their right to pursue their way of life by legal or illegal methods (through "underground" hadarim, yeshivot, etc.).

The imprisonment and expulsion from the Soviet Union of Rabbi J. *Shneersohn, the leader of Habad Hasidism, in 1927 marked one phase in the suppression of Jewish religion. Even after this, "underground" religious activity continued, and its influence was manifested when hundreds of hasidic families left the Soviet Union and went to Erez Israel after World War II.

War was also proclaimed against Hebrew; its study was prohibited, and the publication of books in Hebrew was suspended (though until 1928 it was still possible to print religious books and Jewish calendars). In June 1921 a group of Hebrew authors led by H.N. Bialik and S. Tchernichowsky left Russia. Several years later the Hebrew theater Habimah left the Soviet Union. It had attained a high artistic standard and for several years had been protected from the Yevsektsiya by several of the greatest Russian cultural personalities, led by M. Gorki. The remaining Hebrew authors (Abraham Friman, Hayyim *Lenski, Elisha *Rodin, and others) were cruelly persecuted and many of them sent to forced labor camps.

[Racist Zionism is threefold danger for "Soviet Union" - underground Zionists - ban of Jewish Yevsektsiya section of the Communist Party 1930]

The [[racist]] Zionist movement revealed [[brought up]] great vitality. The Soviets viewed Zionism as a threefold danger.

-- It strengthened the vitality of Jewish nationalism. (col. 463)

-- It diverted the Jewish intelligentsia, whose talents the regime required, toward activities beyond the borders of the Soviet Union (col. 463-464)

-- It maintained relations with the World Zionist Organization, then an ally of England, which ranked among the countries hostile to the Soviet Union.

The Zionist movement went underground. Most of its members were youths and boys who were active in the [[racist]] Zionist parties (Ze'irei Zion; S.S.), youth movements (*Ha-Shomer ha-Za'ir; *Kadimah; and others) and within the framework of He-Halutz which trained its members for aliyah. Many Zionists were imprisoned, sent to labor camps, or exiled to outlying places in Soviet Asia. For several years the Soviets authorized the existence of He-Halutz in certain regions of the country, but this authorization was abrogated in 1928. Thus organized Zionism was silenced by the end of the 1920s.

The independent societies and publishing houses (Hevrat Mefizei Haskalah, the Historical and Ethnographic Society, and others) continued to exist until the late 1920s. Some of their activists succeeded in leaving the Soviet Union (S. Dubnow; S. *Ginzburg). Individuals remained in the Soviet Union (I. *Zinberg).

In 1930 the Yevsektsiya was also disbanded. The first stage in the liquidation of the national life [[religious life]] of the Jews in the Soviet Union had been completed.

[Yiddish] "JEWISH PROLETARIAN CULTURE" [Yiddish newspapers, theaters and writers - Yiddish courts]

To replace the Jewish culture which had been destroyed, the Jewish Communists attempted to develop a "Jewish proletarian culture", which was to be, according to Stalin's slogan, "national in form and socialist in content". This culture was based on the promotion of the Yiddish language and its literature, while the writing of Hebrew works in Yiddish was changed to phonetic transcription, so as to cut the link with Hebrew.

A Yiddish press was established, with three leading newspapers: *Emes (1920-38) in Moscow, Shtern (1925-41) in the Ukraine, and Oktiabr (1925-41) in Belorussia [[Belarus]]. Numerous literary and philological periodicals, youth newspapers, and a trades unions press were published every year. A Yiddish theater network was established. It was headed by the Jewish State Theater under the direction of A. *Granovski (until 1929) and afterward the actor S. *Mikhoels.

These presented adaptions of Jewish classics, by authors such as Mendele Mokher Seforim, Shalom Aleichem, and I.L. Peretz, as well as Yiddish translations of Soviet propaganda pieces and plays. In Minsk and Kiev "Faculties of Jewish Culture" were established in the universities. They essentially promoted research into the Yiddish language and its literature, Jewish folklore, Marxist historiography of the history of the Jews in Russia, and of the Jewish labor movements. The works of these institutes, as well as the whole of Jewish literature, were subject to the supervision of the Yevsektsiya, headed by M. *Litvakov, who kept watch to prevent "nationalist and rightist deviations".

During the short period, between the middle 1920s to the middle 1930s, when this Soviet Yiddish culture florished, it appeared to many adherents of Yiddish in the world that with the assistance of a great power a new Yiddish literature would emerge in the Soviet Union. Jewish authors and scholars who had left the country during the first years after the Revolution, as well as Jews from other countries, began to arrive in Moscow, Kiev, and Minsk (among them the authors D. *Bergelson, P. *Markish, M. *Kulbak, and the scholars N. *Shtif, M. *Erik, and Meir *Wiener).

Yiddish was also given an official status by the establishment of governmental tribunals in which proceedings were held in Yiddish.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 465-466, Hebrew writers in Istanbul in a provisional camp

[Yiddish school system without great success]

The greatest efforts were however invested in the development of a network of Yiddish schools. Many such schools were opened in the towns and (col. 464)

townlets of the Ukraine and Belorussia [[Belarus]]. During the first years an attempt was even made to compel Jewish parents to send their children to these schools. Secondary schools and training colleges for teachers were also established. At the height of this period, in 1932, 160,000 Jewish children (over one-third of the Jewish children of elementary school age) attended these institutions. From this year, however, a decline set in. Jewish parents refused to send their children to schools whose Jewish character, apart from the language of instruction (which was the de-Hebraized Soviet Yiddish), was limited to the study of a few chapters of Yiddish literature and even these were interpreted in a manner which offended the religious and national values of the Jewish people.

A further cause for the decline of this network of schools was the small number of Yiddish secondary schools and the lack of Yiddish higher educational institutions. By the late 1930s these schools began to disappear until they were liquidated, largely of their own accord, in almost every corner of the Soviet Union.

[Assimilation of the Jews by the Russian school system, by mixed marriages - more Russian Jewish writers]

Cultural assimilation gradually gained in momentum among the Jews as they became integrated within the life of the new Soviet society. The majority of the Jewish children attended Russian schools. Jewish youth was attracted to the larger cities where the Yiddish language was nonexistent. Even the Jewish-Russian press, which served as an obstacle to assimilation, and the Jewish societies and organizations were absent there. [...] In 1935 over 60,000 Jews studied at the higher schools (over 10% of the country's students). [...]

Mixed marriages became a frequent occurrence. [...]

An expression of the assimilation of the Jews and their activity in Soviet literature could be seen from their large participation in the first conference of Soviet writers in 1934, at which there were 124 delegates of Jewish nationality (about 20% of the total delegates). Only 24 of them wrote in Yiddish; the others mainly in Russian. These included some of the most prominent authors of Soviet Russian literature, such as I. *Ehrenburg, L. *Pasternak, I. *Babel, and S. *Marshak. The Jews also played a central role in the development of other spheres of Soviet culture, especially the cinema (S. *Eisenstein; Romm).> (col. 467)

Sources

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 459-460

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 463-464

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 467-468

^

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia,

vol. 14, col. 461-462, public prohibiton of

yeshivot schools [[religious Torah schools]]

in Izvestia, 19 June 1919 Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia,

vol. 14, col. 461-462, public prohibiton of

yeshivot schools [[religious Torah schools]]

in Izvestia, 19 June 1919](EncJud_juden-in-SU-d/EncJud_Russia-band14-kolonne461-462-oeff-verbot-yeshivot-19-juni11919-35pr.jpg)