[1920s and 1930s: Zionists

detect the suffering Jews in "Soviet Union"]

<The problems of Russian Jewry had exercised Jewish and

world opinion for many years before the overthrow of czarism

and were the subject (col. 496)

of relief and resettlement project, international protests,

and interventions. In the first years after the October

Revolution of 1917, when Zionist delegations from Russia

were still able to attend world Zionist conferences and

congresses (as in 1920 in London and 1921 in Carlsbad),

attention was given to the turmoil that the civil war and

revolutionary changes were causing to the large and vital

Jewish community in Soviet Russia, and Zionist congresses

adopted resolutions against the suppression of Zionism and

Hebrew by the Soviet regime.

The problem of Soviet Jewry found a place on the agenda of

the founding assembly of the *World Jewish Congress (W.J.C.)

in 1936, but the contemporary widespread sympathy for the

anti-Nazi stance of the Soviet Union and the belief that the

U.S.S.R. had tried to eradicate anti-Semitism and accord

national minority rights to its Jewish population muted

discussion of the question.

[1948-1953: "SU"

antisemitism and news in the Western world]

|

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in "Soviet Union",

vol. 14, col. 497, Paul Yershov, U.S.S.R.

ambassador to Israel and doyen of the diplomatic

corps, greeting [racist Zionist] President

Weizmann and Mrs. Weizmann on the first Irael

Independence Day, May 1949

|

It was only in 1948, with the first indications of official

anti-Semitism in the U.S.S.R. (see *Anti-Semitism: in the

Soviet Bloc), that interest in the problem began to revive.

In spite of Soviet support for the establishment of a Jewish

state in Palestine, the gloom [[darkness]] of impending

[[coming]] developments in the situation of Soviet Jews

could already be felt; and although East European (col. 497)

delegations attended the W.J.C. assembly in 1948, misgivings

about Soviet Jews were tactfully mentioned in the assembly's

report. In general, however, until the events of the

"Black Years" (1948-53), little news of which reached the

outside world, it was assumed that no acute Soviet-Jewish

problem existed and that the difficulties confronting Jews

in the U.S.S.R. were intrinsically [[in fact]] the same as

those afflicting the general Soviet population. When the

campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans" began to sweep the

U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe, however, culminating in the

"Doctors' Plot", a special world Jewish conference on the

situation of Soviet Jews was contemplated [[projected]]. The

W.J.C. assembly meeting in Montreux early in 1953 prepared a

document on the developments; the [[racist]] Zionist

movement held discussions; and other Jewish organizations

anxiously considered what steps might be taken if, as was

feared, the "Doctors' Plot" trial was used as an instrument

for wholesale repression of Soviet Jews. The death of Stalin

in March 1953 and the revocation of the charges against the

doctors ended this tense phase.

|

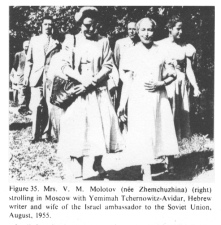

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in

"Soviet Union", vol. 14, col. 497, Mrs. V.M.

Molotov (née Zhemchuzhina) (right) strolling in

Moscow with Yemimah Tchernowitz-Avidar, Hebrew

writer and wife of the Israel ambassador to the

Soviet Union, August 1955 |

1956-1969. [Investigations

about the Jews in the "SU" by Salsberg, Levy - new

publications about "Soviet" Jews in the western world]

In 1956, after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of

the Soviet Union, international opinion again began to stir

on behalf of Soviet Jews. Protests in the Warsaw Yiddish

Communist newspaper

Folkshtime

in April 1956 that the persecution of Soviet Jews had been

passed over in silence in Khrushchev's speech at the 20th

Congress, and the details

Folkshtime

released about the extent and virulence of Stalin's

anti-Jewish terror campaign, made the world realize that the

Jewish problem was still acute after almost 40 years of

Soviet rule. This came as a shock particularly to Jewish and

also non-Jewish Communists. Delegations from Western

Communist parties went to the U.S.S.R. to investigate the

truth.

J.B. Salsberg, a leading Canadian Communist, returned from

such a visit appalled [[frightened]]; he published a series

of articles on the subject in the American and Canadian

Communist press, including details of a meeting with the

Soviet leadership in the party with a group of old-time

Communists.

Hyman *Levy, a founder of the British Communist Party,

prepared a confidential report about his visit in Moscow;

the party executive regarded it as so shocking that only a

strictly censored version was released for publication. Levy

then published a pamphlet in 1958,

Jews and the National Question,

criticizing Soviet policy toward Jews in careful terms, and

he was expelled from the party.

In New York the Communist

Daily

Worker was closed down by the party and was

transformed into a weekly called the

Worker, because its

editors continued to criticize the U.S.S.R.'s treatment of

Jews.

Two pamphlets published in Yiddish in Tel Aviv in 1958,

"Jewish Communists on the Jewish Question in the Soviet

Union", reproduced articles and statements of Jewish

Communists in the West and in Poland.

Individual Jews and organizations in Western countries began

to pay more serious attention to Soviet Jews. A principal

problem was the paucity of reliable information. To meet

this need the newsletter

Jews in Eastern Europe was funded in 1958 in

London, edited by E. *Litvinoff; it subsequently appeared

three or four times a year and became a major source of

factual information about Soviet Jews.

At about the same time the Contemporary Jewish Library was

founded in London to collect and disseminate in photostats

source materials in Russian and other Soviet languages

relating to Jews in the U.S.S.R. under the title

Yevrei i Yevreyskiy Narod

("Jews and the Jewish People"). A branch of the Contemporary

Jewish Library opened in Paris published

Les Juifs en Europe de l'Est

and a monthly bulletin,

Les

Juifs en Union Soviétique. The Biblioteca Judía

Contemporanea in Buenos Aires published (col. 498)

Allà en la U.R.S.R.,

(col. 498-499)

and similar pamphlets were published in Italy. In New York,

Jewish Minorities Research, directed by Moshe Decter,

published monographs, pamphlets, reprints, and other

relevant materials on Soviet Jews, including

The Jews in the Soviet Union by Solomon M Schwarz

(1951);

The Jewish Problem in the

Soviet Union by B.Z. Goldberg (1961);

Jews in the Soviet Union

Census, 1959, edited by Mordecai Altshuler

(Jerusalem, 1963);

a study by the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva

(see below);

"Soixante ans du problème

juif dans la théorie et la pratique du bolchevisme"

by Marc Jarblum with a preface by Daniel *Mayer (in Revue

Socialiste, October 1964)

Soviet Jewry and Human

Rights by Isi Leibler (Human Rights Research

Publication, Victoria, Australia,March 1965;

two reports of the Socialist International (see below).

Particular popularity was achieved by the two eyewitness

accounts, Ben-Ami's (Arieh L. Eliav)

Between Hammer and Sickle

(Heb. 1965; Eng. 1967 and Elie Wiesel's

The Jews of Silence

(1966), which appeared in several languages and editions.

Interesting light was shed on Communist attitudes to the

Jewish problem in the U.S.S.R. by a series of polemical

exchanges in "Political Affairs", the ideological organ of

the U.S.Communist Party, in January 1965, October 1966, and

December 1966.

During the 1960s the problem of Soviet Jewry - the

discrimination against Jews in matters of language,

education, and religion; the dissemination of anti-Jewish

literature; the persecution of individual Jews, e.g., for

"economic crimes" or for Jewish communal activity; and the

denial to Jews of the right of emigration, particularly to

Israel, and the reunification of shattered families - became

a major issue in world Jewish and international discussion.

Almost every Jewish organization, Zionist and non-Zionist

alike, raised the problem as one of utmost importance to the

Jewish people, "second only to the existence and security on

Israel". Intellectuals on the left, Jews and non-Jews, held

special conferences to investigate the facts and issue

appeals to the Soviet government.

The first such conference took place in Paris in 1960 and

was attended by about 50 scholars, writers, academicians,

and parliamentarians from 16 Western and African countries.

Its opening session was addressed by Nahum *Goldmann and

Martin *Buber, and it received messages of support from

Albert Schweitzer, Francois Mauriac, Bertrand Russell,

former French president Vincent Auriol, Richard

Crossman, former Dutch premier Drees, Reinhold

Niebuhr, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, Thurgood

Marshall, Daniel Mayer, and many others.

Subsequent conferences of this kind were held over the years

in Latin American countries, France, Scandinavia, Britain,

and Italy. They were attended and supported by intellectual

and moral authorities, including leading writers, poets, and

prominent fighters for human rights.

[1963: Foundation of the

"Conference on the Status of Soviet Jews" and of the

"American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry"]

Of particular significance was the Conference on the Status

of Soviet Jews in 1963, founded in New York by a meeting of

leading liberals, under the sponsorship of Justice Douglas,

Martin Luther King, Senator H. *Lehman, Bishop James Pike,

Walter Reuther, Norman Thomas, and Robert Penn Warren, which

issued an "appeal to conscience" and published many

documents containing factual material.

At the same time the Jewish community in the United States

established the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry,

which encompassed [[involved]] all the major Jewish

organizations in the country (including the *American Jewish

Committee, which generally did not participate in (col. 499)

comprehensive Jewish frameworks).

This body sponsored

mass rallies, press conferences, and meetings with the White

House and State Department and also published factual

information on the current situation of the Jews in the

U.S.S.R. Similar activities were undertaken by central

Jewish bodies in their respective countries, such as the

Board of Deputies in Britain, the Conseil Représentatif des

Juifs de France, the Executive Committee of Australian

Jewry, etc.

[1967: Foundation of the

"Academic Committee on Soviet Jewry"]

In 1967 an Academic Committee on Soviet Jewry was formed in

the United States; its sponsors included Hans Morgenthau,

Daniel Bell, Saul Bellow, Lewis S. Feuer, Nathan Glazer,

Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Max Lerner, and Lionel Trilling.

The committee became an important source of information and

has issued, among other publications, a booklet entitled

Soviet Jewry: 1969,

consisting of papers read at a symposium by leading Soviet

experts.

[since 1962: Bertrand

Russell]

The moral struggle on behalf of Soviet Jews was given

considerable impetus by the interest shown in the problem by

the philosopher Bertrand Russell. His involvement began

early in 1962, when he sent a cable to Khrushchev, signed

jointly with François Mauriac and Martin Buber, appealing

for the full restitution of equal rights to Soviet Jews. He

also sponsored the publication of a statement on Soviet

Jewry signed by leading Nobel Prize laureates from different

countries. A private exchange of letters between Russell and

Khrushchev on this question followed until, to general

surprise, the Soviet authorities sought Russell's permission

to release part of the correspondence to the Soviet press

and agreed to his condition that he should similarly release

it to the Western press. It was published in Britain on Feb.

25, 1963, and in the U.S.S.R. on February 28, when it

appeared simultaneously in

Pravda and

Izvestiya and was broadcast by Radio

Moscow.

Khrushchev had defined Russell's appeals as part of a

campaign of "vicious slander" against the soviet Union. On

April 6, 1963, Russell replied at length repudiating this

insinuation and describing as "gravely disturbing" the fact

that some 60% of those executed for "economic offenses" in

the U.S.S.R. were Jews. Although the Soviet premier did not

reply to this letter, Russell continued his interventions on

behalf of individual Soviet Jews and the community as a

whole until age caused him to discontinue his public

activities in 1968.

[Russian Jewry mentioned at

the UN and in parliament houses]

The problem began to be reflected at the United Nations, in

parliaments, and in international bodies throughout the

world.

[[The main point about Herzl Israel and the Jews

The main point that Jewry is a religion and not a nation

is not detected by Encyclopaedia Judaica and is not

detected by the governments making statements on the Jews.

The fact is: It's not possible to convert a religion into

a nation because the religion itself has different

branches, and when the religion gets a bad reputation with

a racist state headed against all Arabs. By this many Jews

(the majority!) don't accept this racist Herzl military

Free Mason Zionist Herzl Israel as it is today with it's

cartridges and atomic bombs with the aim of a "Greater

Israel" from the Nile river to the Euphrates river against

all Arabs according to Herzl and 1st Mose chapter 15

phrase 18]].

The first discussion at the U.N. took place in 1961 at the

Subcommission on the Prevention of Discrimination and

Protection of Minorities, and has been a feature of U.N.

debates ever since. [[Palestinians could be mentioned since

1974 only]]. The matter was raised in 1962 at the General

Assembly's Social Committee by the Australian delegate, the

first time it was directly taken up by a member government

other than Israel. this development followed a report by a

delegation to the U.S.S.R. of the World Council of Churches,

which testified that Judaism experienced severe persecution

in that country.

In 1964, before a visit by Khrushchev to Sweden, Denmark,

and Norway was due to take place, the problem of Soviet Jews

was featured by the leading newspapers in all three

countries, and the Soviet premier's visit was "postponed".

The Council of Europe at Strasbourg, consisting of

parliamentary representatives from all democratic countries

in Europe and of official observers from Israel's Knesset,

several times debated the issue and established an

investigating committee to report on it. Its report served

as the basis for the council's appeal to all European

parliaments to raise their voice on behalf of Soviet Jewry.

In the parliaments of Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands,

Sweden, and many other countries, motions were signed by

many members (in Britain over 400 out of 630), and

governments were urged (col. 500)

to appeal to the Soviet Union on this matter. Both houses of

the U.S. Congress also debated the issue and several times

adopted almost unanimous resolutions on it. Leading

statesmen, such as President Eisenhower, President Kennedy,

and the British and Belgian premiers, as well as leaders of

socialist and other opposition parties in the West, took up

the issue in their encounters with Soviet statesmen and

public figures.

In 1964 the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva

published a special study entitled

Economic Crimes in the Soviet Union, which

proved the anti-Jewish character of Soviet policy in this

matter.

Gradually the current situation of the Jews in the Soviet

Union began to be prominently featured in the world press.

Such topics as the anti-Jewish riot at Malakhovka, near

Moscow, the mass gatherings of Jewish youth on Simhat Torah

at the synagogues of Moscow and Leningrad, the ban on

mazzot in the U.S.S.R.,

the virtual dissolution of the Moscow

yeshivah [[religious

Torah school]], the blood libel in the newspaper

Kommunist at Buinaksk,

Dagestan, Yevtushenko's poem "Babi Yar", and anti-Semitic

publications such as Kichko's "Judaism Without

Embellishment" [[without disguise]] were extensively

reported and commented upon in the principal newspapers the

world over and were the subject of sharp debates with Soviet

representatives in various bodies of the U.N. and other

international forums.

[[The western countries - which were lead by racist and

criminal "USA" - never accepted the rights of the Arabs.

Western countries supported the racist Jewish army, never

wanted to get to know about the Zionist aim of Herzl Israel

from Nile to Euphrates and detected Jewish Zionist racism

against Palestinians in the 1970s only when Palestinian

terrorist committed some heavy attacks on Jews in air planes

or on the Olympic games in Munich]].

National and international writers' congresses, as well as

PEN Club meetings, adopted resolutions against the

suppression of Jewish culture in the U.S.S.R. Some Communist

and pro-Soviet circles and press organs, particularly in

Italy, Canada, Britain, the United States, Austria,

Switzerland, Sweden, and Australia, openly criticized Soviet

discrimination against Jews.

[Student groups' agitation

for Soviet Jewry]

In the late 1960s Jewish student groups for the struggle for

Soviet Jewry sprang up in the [[criminal and racist]] United

States, mainly on the east and west coasts, and in Great

Britain, where demonstrations were stage, particularly at

Soviet diplomatic missions. The world Union of Jewish

Students (WUJS) organized a mobile exhibition illustrating

the plight of Soviet Jewry, and mass petitions were signed

by many thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish students.

PARTICIPATION OF [Herzl]

ISRAEL. [Agitation by Jews of Herzl Israel for Soviet

Jewry]

[[Delegates of racist Free Mason Zionist Herzl Israel hid

always their role as to be a satellite of the criminal "USA"

and hid the "Greater Israel" aim against the Arabs. Arabs or

Palestinians were not mentioned, this was the Jewish

solution of the Arab problem]].

Israel representatives were in the forefront of initiating

discussions on the problem in various U.N. bodies, the

Socialist International (which published two reports, in

1964 and in 1969, called

The

Situation of Jews in the U.S.S.R. and

Anti-Semitism in Eastern

Europe), the Council of Europe, etc.

In 1965 the first motion on Soviet Jewry was discussed in

the Knesset. Later the Knesset devoted several special

sessions to the situation of Soviet Jewry and made an appeal

to other parliaments to take up the issue. The problem was

repeatedly dealt with by the Israel press and broadcasting

service and in official and unofficial encounters by

Israel's leaders and diplomatic representatives with Soviet

diplomats and other personalities.

Emigration

drive action 1970-1971

|

|

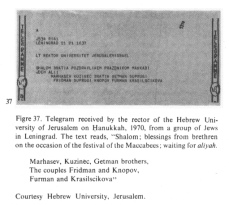

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in "Soviet Union",

vol. 14, col. 503, cable (telegram) from Russian

Jews 1970: Telegram received by the rector of

the Hebrew University of Jerusalem on Hanukkah,

1970, from a group of Jews in Leningrad.

|

|

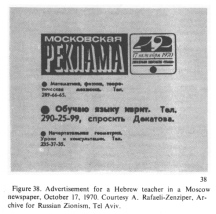

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in "Soviet Union",

vol. 14, col. 504, advertisement searching for

Hebrew teacher in Moscow of 17 October 1970

|

|

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in "Soviet Union",

vol. 14, col. 503-504, advertisment of

solidarity 1970 for the emigration drive

|

|

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in "Soviet Union",

vol. 14, col. 503, Russian Jewish immigrants on

25 March 1971

|

[Books from Soviet Jews in

racist Herzl Free Mason Herzl Israel]

In Israel the Hebrew writings of Soviet Jews, most of them

brought out clandestinely from the U.S.S.R., were published

as early as the 1950s and served as a powerful means of

reviving feelings of solidarity with Soviet Jewry. A

collection of the Hebrew poetry of Hayyim *Lenski and Elisha

*Rodin appeared in 1954 under the title

He-Anaf ha-Gaddu'a

("The Cut-off Branch"). In 1957 the first anonymous Hebrew

manuscript from the Soviet Union, called

El Ahi bi-Medinat Yisrael

("To My Brother in the State of Israel"), which was written

in an old-fashioned

maskil

style, and contained a diary on the "Black Years", was

published, first in the newspaper

Davar and then in book form. (Only after

the author's death in Kiev in 1968, was his name, Barukh

Mordekhai Weissman, revealed).

Under the pen name Sh. Sh. Ron, a Soviet Hebrew writer

described his own and his fellow Jews' experience in a (col.

501)

concentration camp in a smuggled-out booklet,

Me-Ever mi-Sham ("From

Over There", 1959). Unknown and unpublished poems by H.

Lenski, some of which were written in a concentration camp

in Siberia, somehow reached Israel and were published

posthumously in 1960 under the title

Me-Ever li-Nehar ha-Lethe

("From the Other Shore of the Lethe River"), together with

an introduction and postscripts by the poet's friends in

Israel.

A collection of Zionist poetry in its Russian original with

Hebrew translations,

Ha-Lo

Tishali (its Russian title "My Spring Will Come")

by an anonymous Soviet Jew, with an introduction by Y. Nadav

(describing how the poems were written by a member of a

clandestine [[racist]] Zionist group in a labour camp),

appeared in 1962.

A strong impact was made by Esther Feldman's

autobiographical

Kele

Beli Sugar ("Prison Without Bars", 1964), the story

of a Jewish woman in the Soviet Union whose husband (Joseph

Berger-Barzilai) was imprisoned for over 20 years as an

"enemy of the people" and then "rehabilitated".

Soviet Hebrew fiction published in Israel included a novel

about World War II,

Esh

ha-Tamid ("The Eternal Fire", 1966), written by a

writer who hid his identity under the pen name A. Tsefoni,

smuggled out of the U.S.S.R., and Abraham Friman's

monumental novel,

1919,

about the revolutionary years (1968); its first two parts

had been published in the 1930s and received the Bialik

price, whereas the third part was recently smuggled out of

the U.S.S.R. (the fourth part is still missing).

[Children education in

Herzl Israel with data about Soviet Jewry - and hatred

against Arabs]

Educational work to convey deeper knowledge of the history

and the current situation of Soviet Jewry was conducted over

the years in Israel's schools and army units in various

forms, including lectures, classes, a mobile exhibition,

etc. The Hebrew magazine

He-Avar

and various publications of the Israel section of the World

Jewish Congress have devoted themselves to research on

Soviet Jewish affairs.> (col. 502)

[[It can be admitted that the Jewish institutions in Israel

never mentioned the racist Jewish army and never mentioned

the rights of the Arabs. The Jewish children in Herzl Israel

were in fact educated in a hatred against the Arabs. And it

can be admitted that children in the "Soviet Union" got also

an education with facts about racist Zionist Free Mason

Herzl Israel. Only the solution was never found: Jewry is

not a nation, but a religion, and the foundation of a

"Jewish state" within the Arab landscape with the

announcement of borders from Nile to Euphrates river is a

trap of war

because Arab antisemitism is coming up to the antisemitism

which existed until 1945. Human rights should be signed]].

Bibliography

GENERAL WORKS

-- Institute of Jewish Affairs, London: Soviet Jewry (1971),

an extensive bibliography

-- L. Greenberg: The Jews in Russia, 2 vols. (1951)

-- S.W. Baron: The Russian Jew under Tsars and Soviets

(1964)

1772-1917

- J.S. Raisin: The Haskalah Movement in Russia (1915)

-- Dubnow, Hist Russ

-- J. Kunitz: Russian Literature and the Jews (1929)

-- I Levitats: The Jewish Community in Russia, 1772-1844

(1943)

-- J. Frumkin et al. (eds.): Russian Jewry 1860-1917 (1966)

-- V. Nikitin: Yevrei zemledeltsy (1887)

-- M.L. Usov: Yevrei v armii (1911)

-- L. Zinberg: Yevreyskaya periodicheskaya pechat v Rosii

(1915)

-- Yu. Gessen: Istoriya yevreyskogo naroda v. Rossii, 2

vols. (1925-26)

-- S.Y. Borovoy: Yevreyskaya zemledelcheskaya kolonizatsiya

v staroy Rossi (1928)

-- N. Buchbinder: Geshikhte fun der Yidisher Arbeter

Bavegung in Rusland (1931)

-- A. Levin: Kantonistn... 1827-1856 (1934)

-- S. Ginzburg: Historishe Verk, 3 vols. (1937-38)

-- B. Dinur: Bi-Ymei Milhamah u-Mahpekhah (1960)

1917-1971

-- International Military Tribunal: Trials of the Major War

Criminals, 4 (1950), 3-596

-- S.M. Schwarz: The Jews in the Soviet Union (1951)

-- idem: Yevrei v Sovietskom Soyuze s nachala vtoroy mirovoy

voyny (1966)

-- J. Tenenbaum: Race and Reich (1956), 347-70

-- B. West (ed.): Struggle of a Generation: The Jews under

Soviet Rule (1959)

-- idem: Hem Hayu Rabbim (1968)

-- L. Lénéman: La Tragédie des Juifs en U.R.S.S. (1959)

-- J.B. Schechtman: Star in Eclipse:Russian Jewry Revisited

(1961)

-- B.Z. Goldberg: The Jewish Problem in the Soviet Union

(1961)

-- E. Schulman: A History of Jewish Education in the Soviet

Union (1971)

-- E. Wiesel: The Jews of Silence (1966)

-- Gli ebrei nel' U.R.S.S. (1966)

-- Ben-Ami (A. Eliav): Between Hammer and Sickel (1967)

-- S. Rabinovich: Jews in the Soviet Union (Moscow, 1967)

-- L. Kochan (ed.): The Jews in Soviet Russia since 1917

(1970)

-- A. Dagan: Moscow and jerusalem (1971)

-- Jews in Eastern Europe (1958- )

-- S. Agursky: Di Yidishe Komisariatn un di Yidishe

Komunistishe Sekties (1928)

-- N. Gergel: Di Lage fun yidn in Rusland (1929)

-- A. Rafaeli (Zenziper): Eser Shenot Redifot (1930)

-- S. Dimanstein (ed.): Yidn in F.S.S.R. (1935)

-- L. Zinger: Dos Banayte Folk (1941)

-- L. Lestschinsky: Dos Sovetishe Idntum (1941) (col. 505)

-- M. Kahanovitch: Milhemet ha-Partizanim ha-Yehudim

be-Mizrah Eiropah (1954)

-- Y.A. Gilboa: Al Horvot ha-Tarbut ha-Yehudit bi-Verit

ha-Mo'azot (1959)

-- idem: The Black Years of Soviet Jewry (1971)

-- Ch. Chmeruk (ed.): Pirsumim Yehudiyyim bi-Verit

ha-Mo'azot (1961)

-- idem (ed.): A Shpigl oyf a Shteyn (1964)

-- A. Pomeranz: Di Sovetishe Harugey Malkhes (1962)

-- J. Levavi: Ha-Hityashevut ha-Yehudit be-Birobidzhan

-- J. Litvak, in: Gesher, 12 nos. 2-3 (1966), 186-217

-- M. Guri et al. (eds.): Hayyalim Yehudim be-Zivot Eiropah

(1967), 135-57

-- S. Nishmit, in: Dappim le-Heker ha-Sho'ah ve-ha-Mered,

series B. collection A (1969), 152-77

-- S. Redlich, in: Behinot, 1 (1970), 70-79

-- He-Avar (1952- ) (col. 506)

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in

"Soviet Union", vol. 14, col. 497-498

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in

"Soviet Union", vol. 14, col. 499-500 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in

"Soviet Union", vol. 14, col. 501-502 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in

"Soviet Union", vol. 14, col. 503-504 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia: Jews in

"Soviet Union", vol. 14, col. 505-506 |

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia:

Jews in "Soviet Union", vol. 14,

col. 497, Paul Yershov, U.S.S.R. ambassador

to Israel and doyen of the diplomatic corps,

greeting [racist Zionist] President Weizmann

and Mrs. Weizmann on the first Irael

Independence Day, May 1949 Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia:

Jews in "Soviet Union", vol. 14,

col. 497, Paul Yershov, U.S.S.R. ambassador

to Israel and doyen of the diplomatic corps,

greeting [racist Zionist] President Weizmann

and Mrs. Weizmann on the first Irael

Independence Day, May 1949](EncJud_juden-in-SU-d/EncJud_Russia-band14-kolonne497-SU-botschafter-Yershov-m-Weizmann-1949-45pr.jpg)