<BUDAPEST,

capital of Hungary, formed officially in 1873 from the towns

of Buda, Obuda, and Pest, which each had Jewish communities.

Buda (Ger. Ofen).

[Expulsions of 1348 and 1360 - Buda as a royal residence

under King Sigismund]

A community was formed there by the end of the 11th century.

Its cemetery was located near the Buda end of the present

Pest-Buda tunnel under the River Danube. In 1348 and 1360

the Jews were expelled from Buda but returned after a short

interval. As Buda became the royal residence under King

Sigismund (1387-1437), its community rose to prominence in

the Jewish life of the country. Its leaders were entrusted

by the king with the representation of Hungarian Jewry, and

the position of Jewish prefect was held by members of the

Buda *Mendel family who sometimes took part in royal

ceremonies.

[Persecutions since 1490 -

flight to western Hungary in 1526 - deportation to Ottoman

territory - Jews in Buda since 1528 - professions]

After 1490 the Jews of Buda were subjected to continual

persecution, their property was frequently confiscated and

the debts owing them were often unpaid. Following the

Ottoman victory over the Hungarians at Mohács in 1526 many

Jews from Buda fled abroad or to the western part of

Hungary, while the remainder were deported to Ottoman

territory.

Shortly afterward, in 1528, Jews were again living in the

Jewish quarter of Buda. A census of 1547 showed 75 Jewish

residents in Buda and 25 newcomers. During the 150 years of

Ottoman rule the Jews were severely taxed, but their numbers

continued to increase. A conscription roster of 1580

numbered 88 Jewish families, comprising about 800 persons,

including three rabbis, inhabiting 64 houses. They engaged

in commerce and finance, and sometime rose to hold official

posts in the treasury as inspectors or tax collectors. Jews

specialized in the manufacture of decorative braids for

uniforms; the family physician of the pasha of Buda was a

Jew (c. 1550). In 1660 the community numbered approximately

1,000 and was the largest and wealthiest in Hungary.

[Austrian destruction of

the Jewish community - resettlement since 1689 - many

expulsions - Jews prohibited from 1746-1783 under Maria

Theresa]

The ruinous fighting between the Ottoman and Austrian

imperial forces put an end to this prosperity. The Jews

sided with the Turks; when in 1686 Buda was taken by Austria

only 500 Jews survived the siege, the Jewish quarter was

pillaged, and the Torah scrolls were burnt.

Jewish residence in Buda was prohibited until 1689, when a

few Jews began to resettle there and had a prayer room by

1690. In 1703, when Buda was constituted a free royal city,

a struggle began between the Jews of Buda, who preferred to

remain under royal protection, and the citizenry which (col.

1448)

made efforts to extend its jurisdiction to the Jewry. This

culminated in a decree ordering the expulsion of the Jews in

1712. In 1715 Charles III ordered the burghers to end the

continual disturbances and a more tranquil period ensued. A

few Jewish families were exempted by the emperor from

certain restrictions. The exemptions led to an attack and

plunder of Jewish homes in the fall of 1720. Charles

however, again gave them protection. According to a 1735

census, the community numbered 35 families (156 persons),

the majority merchants; five families owned open stalls.

The repeated accusations of the citizenry bore fruit,

however, under *Maria Theresa who in June 1746 issued a

decree ordering the expulsion of the Jews from Buda. The

obstinate resistance of the burghers was broken by *Joseph

II, and in 1783 Jewish residence was again permitted. The

antagonism of the guilds recrudesced during the Hungarian

revolution of 1848 when renewed demands were made for the

Jews' expulsion.

[[The criminal racist Church was the driving force of

anti-Semitism but is never mentioned in this article.

Napoleon times are not mentioned. World War I with it's

migration movements and the collapse of the stock exchange

of 1929 is not mentioned in this article]].

COMMUNAL LIFE.

Organized communal life in Buda dates to the 13th century.

Under King *Matthias Corvinus (1458-90) the head of this

community had jurisdiction over the Jews of the entire

country. During the Ottoman era, Buda Jewry had Sephardi and

Ashkenazi congregations. Two synagogues are known to have

existed in 1647.

RABBIS.

The first rabbi whose name is recorded was *Akiva b. Menahem

ha-Kohen (15th century) known by the honorific of

nasi [[patriarch]]. In

the second half of the 17th century difficulties in finding

appropriate candidates for the rabbinate of Buda compelled

the community to employ as rabbis scholars passing through

Hungary on pilgrimage to Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of

Israel]]. *Ephraim b. Jacob ha-Kohen, a refugee from Vilna,

became rabbi of Buda in 1660. About this time the movement

of *Shabbetai Zevi (Ẓevi) gained a large following in Buda;

a number of rabbis, among them Ephraim's son-in-law Jacob

Sak, supported the messianic movement. The Austrian capture

of Buda is recorded in the

Megillat Ofen [[document roll of Ofen]] of

Isaac B. Zalman *Schulhof. Jacob's son was the celebrated

Zevi (Ẓevi) Hirsch *Ashkenazi (Hakham Zevi (Ḥakham Ẓevi)).

Among rabbis of the Haskalah period [[enlightenment]] was

Moses Kunitzer. Prominent Jews of Buda in the 19th and 20th

centuries include the orator and poet Arnold Kiss (d. 1940),

and the scholar and educator Rabbi Bertalan Edelstein (d.

1934). (col. 1449)

SYNAGOGUES.

The synagogue of the Jewish community of Buda fort is

mentioned in the Buda chronicle of 1307 as having stood

beside the Jews' Gate. It remained in existence until the

expulsion of the Jews from Buda in 1360. The second

synagogue, built in 1461 in the new Jews' Street, survived

until the recapture of Buda. It is mentioned and reproduced

in 17th-century engravings. A Sephardi house of worship has

been revealed, dating back to the Ottoman era. Subsequently

the Jews of Buda could only hold prayer meetings in rented

rooms. In 1866 a temple was built in Moorish style in

Öntöház Street. In the heyday of assimilationism (from the

mid-19th century), especially after the administrative union

of Buda and Pest, the Pest community repeatedly tried to

impose its hegemony on that of Buda, which, however,

succeeded in safeguarding its unique historical character.

The Buda community opened an elementary school in 1830.

Obuda (Hung. Óbuda, Ger.

Alt-Ofen).

"Old Buda", village and later part of Buda. Obuda had a

Jewish community in the 15th century which disappeared after

the Ottoman conquest in 1526. It was rehabilitated from 1712

on, when the Jews lived under the protection of the counts

Zichy, who granted them a charter in 1746, and to whom they

paid an annual protection tax.

The 1727 census records 24 Jewish families living in Obuda,

and the 1737 annual conscription roster, 43. By 1752 there

were 59 families, and the community employed two rabbis and

three teachers; by 1784 there were 109 families with four

teachers.

The 1803 conscription list records 527 families. An

elementary school was opened in 1784, the first secular

Jewish school in the country. Moses *Muenz was rabbi in

Obuda from 1781 to 1831. the Jewish linen weavers of Obuda

won a reputation for the town; the Goldberger factory had an

international reputation.

After the revolution of 1848-49 a large contribution was

levied on the Obuda community. The old synagogue of Obuda

was demolished in 1817 and an imposing new one, still in

existence, was consecrated in 1820. Julius *Wellesz was

rabbi of Obuda from 1910 to 1915.

[[The criminal racist Church was the driving force of

anti-Semitism but is never mentioned in this article.

Napoleon times are not mentioned. World War I with it's

migration movements and the collapse of the stock exchange

of 1929 is not mentioned in this article]].

Pest.

[Jews under Ottoman rule -

anti-Semitic Austrian rule - Jews prohibited 1686-1786 -

"toleration tax" 1786-1846]

Jews are first mentioned in Pest in 1406; in 1504 they owned

houses and land. Records again mention Jews living in Pest

from the middle of the 16th century [[under Ottoman rule]],

and a cemetery is known to have existed by the end of the

17th.

After the Austrian conquest in 1686, Jewish residence within

the city was prohibited. In the middle of the 18th century

Jews were allowed to attend the country-wide weekly markets

held in Pest, but the only Jews permitted to stay in the

city for a specified time were Magranten ("transients"; see

*Familiants laws). In 1783 Joseph II abrogated the municipal

charter with its exclusion (col. 1450)

privileges and permitted Jews to resettle in Pest. The first

"tolerated" Jew received permission to settle within the

city walls in 1786 in return for paying a "toleration tax"

to the local governorate. Article 38 of the

De Judaeis law passed

in 1790 ratified the legal position of the Jews established

under Joseph II.

In Pest, however, the law was understood to apply only to

Jews living there before 1790, hence new arrivals were not

permitted to settle permanently. An attempt was even made to

expel the married children of the "tolerated" Jews. In 1833

there were 1,346 Jewish families in Pest. The restrictions

on Jewish residence were abrogated by Article 29 of the

annual national assembly of 1840. Jews had the right to

establish factories, and engage in trade and commerce as

well as to acquire property. Pest Jewry took the lead in

pressing for the abolition of the tolerance tax, and in 1846

the "chamber dues" were abolished.

[Revolution of 1848 with

riots against Jews - "contribution" - emancipation and

prosperity]

On the outbreak of the Hungarian revolution of 1848, Jews

volunteered for civil defense, but the German citizens of

Pest objected to their enrollment. On April 19 a mob which

attacked the Jewish quarter was repelled by the military.

Nevertheless many Jewish youths enlisted in the

revolutionary army, and the Jews of Pest gave large

financial contributions to the revolutionary cause. After

the suppression of the revolt, a huge contribution was

levied on the Pest community, and to help the Obuda and Pest

communities a collection was made by Hungarian Jewry of

1,200,000 forints.

The Pest community played a leading role in the struggle for

*emancipation in Hungary. The half century preceding World

War I was a period of prosperity and cultural achievement

for Pest Jewry. Their numbers increased, and they played a

prominent role in the capital's economic development. Max

*Nordau and [[racist]] Theodor *Herzl were born there during

this period. With the growth of Nazism before World War II

Jewish communal and economic life was again restricted.

[[The criminal racist Church was the driving force of

anti-Semitism but is never mentioned in this article.

Napoleon times are not mentioned. World War I with it's

migration movements and the collapse of the stock exchange

of 1929 is not mentioned in this article]].

COMMUNAL LIFE.

Active community life is not recorded in Pest until the

first half of the 18th century. The first synagogue was

opened in 1787, and in 1788 the community received a burial

site from the municipality; Moses Muenz of Obuda officiated

as rabbi. The first rabbi of Pest (1793), was Benjamin Ze'ev

(Wolf) *Boskowitz. Other noted rabbis of the community were

Loew *Schwab, S.L. Brill, W.A. Meisel, S. *Kohn, M.

*Kayserling, S. *Hevesi, and J. (col. 1451)

*Fischer. The new constitution for the religious community,

approved by the local authorities, came into effect in 1833.

The noted Orientalist I. *Goldziher served as secretary of

the Neolog community of Pest from 1874 to 1904. A separate

Orthodox community was established in Pest in 1871. Koppel

*Reich became its rabbi in 1886, and a member of the

Hungarian upper house in 1926.

See *Orthodoxy, *Reform, *Hungary.

SYNAGOGUES.

The Jews of Pest rented a place for worship in the Orczy

building in 1796, whose congregation observed the

conservative ritual; a more progressive temple existed in

the same building, known as the "Kultustempel". In 1859 a

double-turreted Moorish-style temple was built in Dohány

Street. Construction of the octagonal temple in Rombach

Street was completed in 1872. In 1913 the synagogue of the

Orthodox congregation was erected in Kazinczy Street.

EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS.

The first Jewish school in Pest was established in 1814 by

Israel *Wahrmann. A Jewish girls' school was opened in the

fall of 1852 and in 1859 a Jewish teachers' training college

was founded. After the attainment of emancipation, a number

of Jewish schools closed down, including those in Buda and

Obuda. The Orthodox congregation of Pest opened its school

for boys in 1873. The Rabbinical Seminary and its secondary

school (gymnasium), opened in 1877, helped to make Pest the

center of Jewish learning. The Pest community established a

comprehensive secondary school in 1891.

Following the widespread anti-Semitism aroused by the

*Tiszaeszlar blood libel case in 1882, the idea of

establishing a Jewish secondary school (gymnasium) found

increasing support, and in 1892 Antal Freystaedtler donated

one million forints for this project. The school was opened

in the fall of 1919 as the Pest Jewish Boys' and Girls'

Gymnasium. Because of the existing discriminatory

restrictions, the Pest community also opened an engineering

and technical college and a girls' technical college. The

rabbinical seminary and a secondary school continue to

function.

WELFARE INSTITUTIONS.

Welfare and communal institutions of the Pest community

included a hospital, opened in 1841; the hospital of the

Orthodox congregation (col. 1452)

opened in 1920; the Hungarian Jewish Crafts and Agricultural

Union (MIKEFE), established in 1842; the Pest Jewish Women's

Club, founded in 1868, which established an orphanage for

girls in 1867; an orphanage for boys, established in 1869;

the deaf and dumb institute, founded in 1876; and the blind

institute, founded by Ignác Wechselmann and his wife in

1908. (col. 1453)

[[The criminal racist Church was the driving force of

anti-Semitism but is never mentioned in this article.

Napoleon times are not mentioned. World War I with it's

migration movements and the collapse of the stock exchange

of 1929 is not mentioned in this article]].

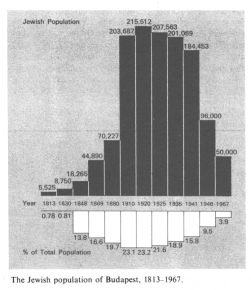

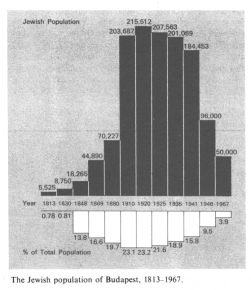

POPULATION.

the annual registers of 1735-38, the first to show the

number of Jewish families residing in the area which forms

Budapest today, recorded 2,531 heads of families of whom

1,139 engaged in commerce. The Jewish population increased

with the development of a capitalist economy and the growth

of Budapest into a metropolis and reached its highest level

in the period preceding and immediately following World War

I. Subsequently it declined sharply due to the lowered

birthrate, an increasing number of conversions to [[racist]]

Christianity, and emigration during the counterrevolution

and the *Horthy regime. There were 44,890 Jews living in

Budapest in 1869, 102,377 in 1890, 203,687 in 1910, 215,512

in 1920, and 204,371 in 1930.

[J.Z.]

[[Emigration movement after the collapse of the stock

exchange of 1929 was going on]].

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Budapest, vol. 4, col. 1450.

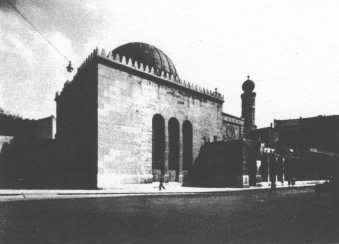

The Heroes' Synagogue

in Budapest, built in 1929. Photo C.A.H.J.P., Jerusalem

In 1941 there were about 184,000 Jews in Budapest out of a

total population of 1,712,000. Since the number of

Christians considered as Jews, in accordance with the

anti-Jewish laws then in force (see *Legislation,

anti-Jewish, Hungary) was 62,000, the total number of

persons subjected to persecutions as Jews was 246,000. From

Hungary's entry into the war in the summer of 1941 until the

German occupation on March 19, 1944, 15,350 members of

Budapest's Jewish population perished in labor detachments

and through deportation (see *

Hungary).

After the Germans entered Hungary, *Eichmann's

Sondereinsatzkommando (see *Holocaust, General Survey) and

the *Sztójay Government set up the Budapest Jewish Council,

deprived the city's Jews of freedom of movement, and, on

April 3, 1944, decreed the wearing of the yellow *

badge.

By the end of July some 200,000 Jews had been herded

together in about 2,000 houses distinctly marked with yellow

badges. These Jews were to be deported in July-August, after

the Jews of the provinces were deported.

Rescue actions by neutral states (mainly Switzerland and

Sweden) were started by Charles *Lutz and Raoul *Wallenberg

in June-July. Thousands of Jews found shelter in so-called

"protected houses", or in the legations of the neutral

powers.

[[Swiss government was not

"neutral"

The anti-Semitic Swiss government of Switzerland played a

cruel game with the world serving the Nazi administration up

to the end giving credits and with help for any transaction

and working force for the Wehrmacht up to the end of the

war, stamping passports with a "J" and rejecting Jews at the

frontiers etc. The pro-Jewish actions were a welcome mean

for the later history propaganda after 1945, and the Nazi

line of the Swiss government was hidden up to the 1990s...]]

A certain improvement in the conditions of the Jews was felt

in August-September, when Horthy sought contacts with the

Allies. Eichmann had to leave Budapest at the end of August,

and the deportation was called off.

[Arrow-Cross government

1944-1945 - Eichmann coming back, riots, ghettos - the

"International Ghetto" of Budapest - forged passports -

deportations and death marches]

On October 15, 1944 the *Arrow-Cross movement seized power,

and, on the same day, began a series of pogroms which

decimated the Jewish population. On October 17, Eichmann

returned to Budapest, the yellow-badge houses were closed

down, and the concentration of Jews into two big ghettos

began. By the end of December the population of the Central

Ghetto amounted to 70,000.

Tens of thousands of Jews possessing safe-conduct passes

issued by the neutral powers were crowded into the

International Ghetto. Officially, some 7,800 Swiss, 4,500

Swedish, 2,500 Vatican, 698 Portuguese, and 100 Spanish

Schutzpaesse

(safe-conduct passports) were issued. In fact the number of

legal and forged safe-conducts approached 100,000.

On November 5, 1944, the Hungarians began handing (col.

1453)

over Jews to the Germans. Some 76,000 Budapest Jews were

involved in the death march and deportations that followed.

Throughout December the terror grew in intensity. At the

beginning of January 1945, the government withdrew its

recognition of international safe-conduct passes. Jews were

hunted all over Budapest by Arrow-Cross bands and shot by

the thousands. The liquidation of the ghettos was planned

for mid-January, but the Red Army took the city after long

street fighting in January 1945. The International Ghetto

was liberated on January 16, and the Central Ghetto two days

later.

[Communist occupation of

Budapest since January 1945]

At the time of Budapest's liberation [[Communist

occupation]], some 94,000 Jews remained in the two main

ghettos and in the legations of the neutral powers. The

number of Jews in hiding was about 25,000. Later, some

20,000 returned from concentration camps and from labor

service detachments. Of those Budapest inhabitants

considered to be Jews, about 105,000 perished between March

19, 1944, and the end of the war. Since 15,350 Jews died

during the period preceding the occupation, almost 50% of

Budapest's inhabitants of Jewish origin died during the

Holocaust period.

[[There is no number about the hideouts, changing religion

or changing name. Jews who had changed religion or changed

their name with forged documents were not counted as Jews

any more and failed in the statistics. This is missing in

this article. Also the fact that many Jews were drawn into

the Red Army for fighting on the front in 1945 and died on

the front is not mentioned in the article]].

See also *Hungary.

[B.V.] (col. 1454)

Contemporary Jewry.

[Number - unification of

the Jewish communities of Buda, Obuda and Pest in 1950 -

exodus of 1956 - Jewish cultural life]

Approximately 80,000-90,000 Jews remained in Budapest after

World War II. (col. 1454) [[...]]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Budapest, vol. 4, col. 1449.

Graphics

of the Jewish population of Budapest, 1813-1967

In 1950 the Orthodox community and the communities of Pest,

Buda, and Obuda were unified by government order, forming

the Budapest Jewish community existing under conditions

similar to the prevailing in other communities in Soviet

satellite states. (col. 1453) [[[...]]

During the period of liberalization in 1956 between 20,000

and 25,000 Jews left the city. [[...]]

Jewish affairs were conducted by the Department of Religious

Affairs, controlled by the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Jewish life in Budapest, as in the entire country, was

centered around religious life. There were twenty rabbis in

the city and in each of the 18 administrative districts in

Budapest, there was at least one synagogue, a rabbi, a

talmud torah, and a

meeting hall for lectures. Budapest had the largest European

synagogue, and perhaps the largest in the world, that of

Dohány Street.

Besides the

talmudei

torah, there was an all-day secondary school, with

close to 140 students. The language of instruction was

Hungarian. The religious community was divided into Orthodox

and Neolog branches. The Orthodox one maintained a yeshivah

[[religious Torah school]] with about 40 students, and the

Neolog one supported a rabbinical seminary with

approximately ten students. It was estimated that 80% of the

community was of Neolog tendency. This phenomenon was

probably due to the mass extermination of Orthodox Jews

during the Nazi occupation and large immigration of Orthodox

Jews to [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel.

Religious facilities, such as kosher slaughtering and baking

mazzah (maẓẓah), were freely available. The community

maintained a Jewish hospital with beds for 224 patients,

staffed by ten Jewish doctors and equipped with a kosher

kitchen. In addition, the community supported a home for the

aged and a canteen where needy people received free meals.

The communal publication was the widely read biweekly

Úy Élet [[New Life]],

which was informative about Jewish communal affairs.

Although Jewish life was intense, the participation of the

youth in communal affairs and in religious life was

negligible. [[...]]

In 1968, 60,000-70,000 Jews lived in Budapest. [[...]]

[ED]> (col. 1454)