<HUNGARY, state

in S.E. Central Europe.

Middle Ages to the Ottoman

Conquest.

[Roman legions - Middle

Ages - crusades - Jews in "important communities"]

Archaeological evidence indicates the existence of Jews in

Pannonia and Dacia, who came there in the wake of the Roman

legions.

Jewish historical tradition, however, only mentions the Jews

in Hungary from the second half of the 11th century, when

Jews from Germany, Bohemia, and Moravia settled there. In

1092, at the council of Szabolcs, the Church prohibited

marriages between Jews and Christians, work on Christian

festivals, and the purchase of slaves. King Koloman

protected the Jews in his territory at the end of the 11th

century, when the remnants of the crusader armies attempted

to attack them (see *Crusades).

Jews resided only in towns ruled by the bishops where

important communities developed: in Buda (see *Budapest;

12th century), Pressburg (*Bratislava, Hung. Pozsony; first

mentioned in 1251), Tyrnau (*Trnava, Hung. Nagyszombat), and

*Esztergom (by the middle of the 11th century).

[Professions of the Middle

Ages - criminal Church against the Jews - Black Death

persecution of 1349]

During the 12th century the Jews of Hungary occupied

important positions in economic life. The nobles felt it

necessary to curb this development, and in the "Golden Bull"

(1222) an article was included which prohibited the Jews

from holding certain offices and from receiving titles of

nobility. The legal status of the Jews was settled by King

Bela IV in a privilege of 1251, which follows the pattern of

similar documents in neighboring countries. As a result of

the Church Council of Buda in 1279, Jews were forbidden to

lease land and compelled to wear the Jewish *

badge.

In practice, these decrees were not applied strictly because

of the king's objection.

During the reign of Louis the Great (1342-82), the hostile

influence of the Church in Jewish affairs again

predominated. The *Black Death led to the first expulsion of

the Jews from Hungary in 1349. A general expulsion was

authorized though they were subjected to restrictions.

[A special "judge of the

Jews" since 1365 - Corvinus government 1458-1490]

In 1365 the king instituted the office of "judge of the

Jews", chosen from among the magnates, who was in charge of

affairs concerning Jewish property, the imposition and

collection of taxes, representation of the Jews before the

government, and the protection of their rights.

The reign of Matthias Corvinus (1458-90) marked a change in

favor of the status of the Jews, despite his support of the

towns, whose inhabitants, the overwhelming majority of whom

were Germans, were inimical to the Jews as dangerous

rivals.

[Jews at stake and riots in

1494 - all "Christian" debts canceled by King Ladislas VI

- direct protection since 1515 under Maximilian I -

degrading oath 16th-19th century]

In 1494 there was a *blood libel in Tyrnau and 16 Jews were

burned at the stake. In its wake, anti-Jewish riots broke

out in the town; these were repeated at the beginning of the

16th century in Pressburg, Buda, and other towns. The

economic situation of the Jews was also aggravated: King

Ladislas VI (1490-1516) canceled all debts owing to the

Jews. [[Probably criminal Church was the thriving

anti-Semitic force]]. In 1515, however, the Jews were placed

under the direct protection of Emperor Maximilian I (the

pretender to the crown of Hungary).

During this period, a degrading form of Jewish *oath before

the tribunals was introduced; it remained in force until the

middle of the 19th century.

[Anti-Jewish measured under

Louis II - tax rise for the war against the Turks]

During the reign of Louis II (1516-26) hatred of the Jews

intensified as a result of the activities of Isaac of

Kaschau, the director of the royal mint, and the apostate

Imre (Emerich) Szerencsés (Latin: Fortunatus), the royal

treasurer who devalued the currency and raised the taxes in

order to provide funds for the war against the Turks.

[Community life in Hungary

during 14th-15th century]

During the middle of the 14th century the most important

Hungarian community was that of *Szekesfehérvar (Ger.

Stuhlweissenburg), whose

parnasim

[[communal leaders]] also directed the general affairs of

the Jews of the country. During the 15th century the

community of Buda gained in importance (col. 1088)

as Jews expelled from other countries also settled there.

Little information is available on the spiritual life of

Hungarian Jewry during the Middle Ages. Apparently it was

poor in comparison to that in neighboring countries because

of the dispersion of the communities and the small number of

their members. The first rabbi whose reputation spread

beyond Hungary was *Isaac Tyrnau (late 14th-early 15th

century); in the introduction to his

Sefer ha-Minagim ("Book

of Customs") he describes the poor condition of Torah study

in Hungary.

Period of the Ottoman

Conquest. [Turkish rule 1526, Ottoman rule 1541

"relatively satisfactory"]

The first, temporary Ottoman conquest of Buda in 1526 caused

many of the Jewish inhabitants to join the retreating Turks.

As a result of this movement, congregations of Hungarian

Jews formed within the important communities of the Balkans.

After central Hungary was incorporated within the Ottoman

Empire in 1541, the Jewish status was relatively

satisfactory. Jewish settlement in Buda was renewed, and

Sephardim of Asia Minor and Balkan origin also settled

there. During the 17th century Buda was one of the most

important communities of the Ottoman Empire. This was

largely due to the authority of its rabbi, *Ephraim b. Jacob

ha-Kohen, author of

Sha'ar

Efrayim (1688).

["Christian" Hapsburg rule

with growing anti-Semitism - Jews at stake in 1529 -

expulsions - influx of Vienna Jews in 17th century -

Reformation changing the law]

In the Hapsburg dominions of Hungary in this period hatred

toward the Jews increased. In 1529, following a blood libel

in Bazin, 30 Jews were burned at the stake and the others

were expelled from the town. The Jews were also expelled

from Pressburg, Oedenburg (*Sopron), and Tyrnau. However,

the magnates of western Hungary accorded their protection to

the Jews expelled from the towns. The Jews expelled from

Vienna found refuge on the estate of Count Esterhazy in

*Eisenstadt and six small neighboring towns in 1670. It was

the oldest of the *Seven Communities" of *Burgenland,

granted autonomy in a privilege issued in 1690.

In *Transylvania, under the rule of Gabriel Bethlen

(1613-29), the status of the Jews was stabilized by a

privilege granted in 1623. The favorable attitude toward the

Jews there stemmed from *Reformation influences in

Transylvania (see also Simon *Péchi).

18th to 19th Centuries

(Until 1867). [Almost no Jews left - Hapsburg rule -

anti-Semitism of the townsmen]

By the beginning of the 18th century, when most of Hungary

came under Hapsburg rule, only a few remnants of the ancient

Jewish settlement were to be found there.

[[Probably the Jews had left with the Ottoman army for

Istanbul (Constantinople) where there was a big Jewish

community under tolerant rule, see: *

Constantinople

/

Istanbul]].

At this time, however, a movement of Jewish migration began,

marking the formation of Hungarian Jewry of the modern ear.

The census of 1735 enumerated 11,600 Jews (in reality, their

numbers were far greater) of whom only a few were born in

Hungary, while the majority had come from Moravia and the

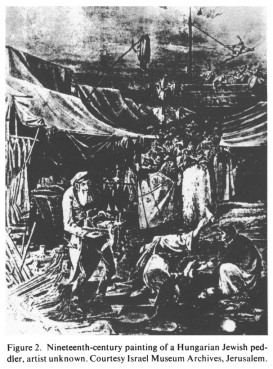

minority from Poland. Most of the Jews were peddlers and

small tradesmen. Because of the hostility of the townsmen,

most of them lived in the villages.

[Maria Theresa: rising

"tolerance tax" since 1744 - Jews in royal cities since

Joseph II since 1783]

During the reign of *Maria Theresa (1740-80) the situation

of the Jews deteriorated. In 1744 an annual "tolerance tax"

of 20,000 guilders was levied on them. It was gradually

increased, until it amounted to an annual sum of 160,000

guilders at the beginning of the 19th century. The reign of

*Joseph II brought some improvements. In 1783 Jews were

authorized to settle in the royal cities. There were 81,000

Jews in Hungary in 1787.

[[Napoleon times, Napoleon reforms and reverse anti

revolutionary movement after 1815 are not mentioned in this

article]].

[Reforms and revolution of

1848-1849 - almost emancipation in 1859-1860 -

emancipation in 1867]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Hungary, vol. 8, col. 1097.

Nineteenth-century painting of a

Hungarian Jewish peddler, artist unknown. Courtesy Israel

Museum Archives, Jerusalem.

During the "period of reform" in Hungary in the 1830s and

1840s, the Jewish question was discussed in the legislative

institutions, in literature, and in the periodicals and

press. In general there was a marked tendency in favor of

granting civic rights to the Jews, but on the whole society

took a critical view of the Jews and assumed an attitude of

reservation toward them, demanding religious and social

reforms (see *Emancipation).

The suppression of the revolution of 1848-49 also affected

the status of the Jews. Because many of them were active in

the revolution, the (col. 1089)

Austrian military government imposed a collective fine of

2,300,000 guilders on the communities; it was later reduced

to 1,000,000 (in 1856, the sum was reimbursed in the form of

a fund for educational and relief institutions). During the

1850s, the Jews were still subjected to judicial and

economic restrictions (the Jewish oath; the need for a

marriage permit; the prohibition on acquiring real estate;

and others).

Most of the restrictions were abolished in 1859-60; the Jews

were authorized to engage in all professions and to settle

in all localities. The first political leaders of the new

Hungary, including Count Gyula Andrássy, Ferencz *Deák, and

Kálmán *Tisza, expressed their approval in the granting of

civic and political equality to the Jews, and after the

Compromise with Austria, the bill on Jewish emancipation was

passed in Parliament without considerable opposition (Dec.

20, 1867).

[Numbers]

During the same period there was a rapid growth of the

Jewish population of Hungary, due both to natural increase

and immigration from neighboring regions, especially

Galicia. The number of Jews had risen to 340,000 by 1850,

and in the first population census held in modern Hungary

(1869), 542,000 Jews were enumerated.

The Emancipation Period,

1867-1914.

During this period Hungarian Jewry consolidated from the

political, economic, and cultural aspects and succeeded in

establishing a strong position in the life of the country.

Jews played a considerable role in the development of the

capitalistic economy of Hungary, and from the 1880s large

numbers entered the liberal professions, and also

contributed to literary life, in particular in journalism.

In economic activity Jews in Hungary were especially

prominent from the mid-19th century in the marketing and the

export of agricultural produce.

[Professions]

Emancipation offered a wide scope for Jewish economic

initiative in the establishment of banks and other financial

enterprises. Jewish capital contributed significantly to the

financing of heavy industry at the close of the 19th

century. The role of the Jews in agriculture was also

considerable, as owners of estates and in particular as

contractors in agricultural management and marketing. (col.

1090) [[...]]

[Political anti-Semitism

since 1870s - growing anti-Semitism since the 1880s -

blood libel in 1882]

From the mid-1870s political anti-Semitism emerged as an

ideological trend, subsequently to become a political force,

led by a member of Parliament, Gyözö Istóczy. The driving

forces behind it were the resentment felt by those classes

which were dispossessed by the capitalistic economy and the

effects of recent social changes. Thus the main bearers of

anti-Semitism were the gentry. German examples also played

some part in Hungarian anti-Semitism.

At the beginning of the 1880s anti-Jewish propaganda

intensified [[the Jews were blamed of the murder of the

czar]] and reached a climax with the blood libel of

*Tiszaeszlar in 1882, which aroused much emotion and was the

cause of severe anti-Jewish disturbances in several towns.

The acquittal of the accused and the (col. 1090)

condemnation of the libel by many gentile leaders did not

calm feelings. In 1884 an anti-Semitic faction of 17 members

of parliament was organized but it did not wield much

influence there, owing to internal dissension. Jewish

defense against anti-Semitism took the form of apologetic

and polemic literature. In face of the emphatic attitude of

the government and the main political parties against

anti-Semitism, it was deemed unnecessary to initiate any

organized action. (col. 1091)

[Jewish religion officially

recognized in 1895]

In 1895 the Jewish religion was officially recognized as one

of the religions accepted in the state, and accorded rights

enjoyed by the Catholic and Protestant religions. The law

was enacted despite vigorous objection from the Catholic

Church and its allies the magnates, who succeeded in

delaying its ratification on three occasions. (col. 1090)

[[...]]

[Strong anti-Semitic

Catholic People's Party since 1900 - criminal Church and

clerical anti-Semitism - anti-Semitic nationalism]

At the turn of the century the Catholic People's Party

became the main bearer of anti-Semitism. It regarded it as

its main task to combat alleged anti-Christian and

destructive ideas, especially Liberalism and Socialism,

which according to clerical presentation was closely

associated with the Jews. Jewish intellectuals and their

allegedly harmful influence were a particular target for

unrestricted attack.

Jewish reaction to clerical anti-Semitism was stronger, more

pronounced and more courageous than to the anti-Semitism in

the 1880s, which seemed to be less menacing. Many of the

tenets of anti-Semitism in this era became cornerstones of

the anti-Jewish ideology in the inter-war period.

Anti-Semitism was also widespread among the national

minorities, especially the Slovaks, principally kindled

because the Jews tended to identify themselves with the

nationalist policy of the Magyars. (col. 1091) [[...]]

Internal Life during the

19th Century.

[Languages Yiddish and Hungarian - Jews in three regions -

nationalism provoking struggle]

In origin, spoken language, and cultural tradition and

customs, Hungarian Jewry was divided into three sections:

the Jews of the north-western districts (Oberland) of

Austrian and Moravian origin, who spoke German or a western

dialect of Yiddish; the Jews of the northeastern districts

(Unterland) mostly of (col. 1091)

Galician origin, who spoke an eastern dialect of Yiddish;

and the Jews of central Hungary, the overwhelming majority

of whom spoke Hungarian. [[...]] The threefold split left

its imprint on the internal organization and life of

Hungarian Jewry until the Holocaust. [[...]] In the

classification of the inhabitants according to nationality,

the overwhelming majority of the Jews in Hungary declared

themselves members of the Hungarian nation; Jewish

nationality was not officially recognized and the Jews thus

became a party in the struggle between the ruling Magyar

nation and the national minorities of Hungary. (col. 1092)

[[...]]

[Split between reformists

and Orthodox Jews]

The internal life of the Jews of Hungary during the 19th

century was marked by polemics between the Orthodox on the

one hand and those advocating modern culture, integration,

and *assimilation on the other.

At the beginning of the century, a strict Orthodox trend was

established in Hungary under the leadership of Moses *Sofer

of Pressburg. This town became a spiritual center for the

Orthodox Jews of Hungary, and its yeshivah [[religious Torah

school]] the most important in central Europe; it exerted

much influence over the Hungarian communities and even

beyond them.

From the 1830s, Haskalah [[enlightenment]] made its

appearance in Hungary, and the movement of religious

*Reform, whose leading spokesmen there were Aaron *Chorin

and Leopold *Loew, spread to several communities. Extreme

Reform did not strike roots in Hungary, but the wish to

introduce reforms in education and religious life made

progress and aroused violent opposition from the Orthodox.

The polemics between the Orthodox and the reformers (who in

Hungary were referred to as Neologists; see *Neology) gained

in intensity to become a central issue at the General Jewish

Congress convened by the government in 1868.

[Autonomy of the Jewish

community - Orthodox opposition]

The Congress was called in order to define the basis for

autonomous organization of the Jewish community. It was

attended by 220 delegates (126 Neologists, and 94 Orthodox).

The conflict between the factions was aggravated when the

majority refused to accept the demands of the Orthodox on

the validity of the laws of the Shulhan (Shulḥan) Arukh in

the regulations of the communities. A section of the

Orthodox opposition left the Congress, which continued with

its task and established regulations for the organization of

the communities and Jewish education. The organizational

structure was to be based on the existence of local

communities, on regional unions of communities, and on a

central office which was to be responsible for relations

between the authorities and the communities.

The Orthodox did not accept these regulations, and

particularly opposed those concerning the existence of a

single community in every place. They appealed to Parliament

to exempt them from the authority of these regulations.

Parliament consented to their demands (1870) and the

Orthodox began to organize themselves within separate

communities. There were also communities which did not join

any side and retained their pre-Congress status (the *status

quo communities). (col. 1092) [[...]]

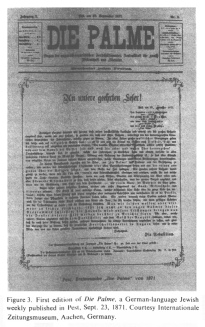

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Hungary, vol. 8, col. 1100.

First edition of "Die Palme", a German-language

Jewish weekly published in Pest, Sept. 23, 1871. Courtesy

Internatinale Zeitungsmuseum, Aachen, Germany.

Moses Sofer and his school decisively influenced the

development of Orthodox Jewry in western and central

Hungary. Torah study became widespread among large sections

of Orthodox Jewry, and yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]]

were established in every large community. The most renowned

of these, besides that of Pressburg, were those of *Galanta,

Eisenstadt, *Papa, Huszt (*Khust), and Szatmar (*Satu-Mare).

During the 19th century the Hungarian rabbinate was of a

high standard and produced halakhists, authors of religious

works, and community leaders, such as Sofer's son Abraham

Samuel Benjamin *Sofer and grandson Simhah (Simḥah) Bunem

*Sofer, Moses Schick, and Judah Aszód (1794-1866) in

Szerdahely (Mercurea), Aaron David Deutsch (1812-78) in

Balassagyarmat, Solomon *Ganzfried, and (col. 1092)

others. Torah literature underwent a considerable

development, and a place of importance was held by learned

periodicals in this sphere.

*Hasidism (Ḥasidism) spread in the northeastern regions of

Hungary, where it did not encounter violent opposition from

the rabbis. Isaac Taub is regarded as having introduced

Hasidism (Ḥasidism) into Hungary; after his death the

Hasidim (Ḥasidim) there gathered around Moses *Teitelbaum in

Satoraljaujhely. He founded a hasidic- (ḥasidic)-rabbinical

dynasty which was active in the Maramarossziget (Sighet) and

its surroundings. Another center of Hasidim (Ḥasidim) was

Munkacs (*Mukachevo), in Carpathian Russia, where Isaac

Elimelech *Shapira settled. In addition, the dynasties of

the zaddikim (ẓaddikim) [[ultra-Orthodox Jews]] of *Belz,

Zanz, and *Vizhnitz had considerable influence in Hungary.

Hasidism (Ḥasidism) left its imprint on the Jews of the

northeastern regions, and differences in customs and way of

life arose between the Hasidim (Ḥasidim) in Hungary and the

section influenced by Pressburg and its school.

[Assimilation movement]

From the close of the 19th century, assimilation became

widespread within Hungarian Jewry and there was an increase

in apostasy especially among the upper classes. Mixed

marriage became a common occurrence, particularly in the

capital [[of Budapest]].

[Racist Zionists - racist

Theodor Herzl from Budapest]

Attachment to Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of Israel]]

was already ingrained within Hungarian Jewry from the period

of Sofer, upon whose recommendation some of his

distinguished disciples had emigrated to Erez Israel [[Ereẓ

Israel]] where they ranked among the leaders of the

Ashkenazi

yishuv

[[Jews in Palestine before Herzl Israel foundation, before

1948]] during the middle of the 19th century.

During the *Hibbat (Ḥibbat) Zion period, Josef *Natonek was

active in Hungary, and some believe that this activity

influenced [[racist]] Theodor *

Herzl,

who was born in Budapest and spent his childhood and youth

in Hungary. The nationalist ideal and political Zionism,

however, only seriously attracted a limited circle of the

academic youth, the intellectuals, and a minority of

Orthodox Jewry, while assimilationist circles and the

overwhelming majority of the Orthodox were sharply and

firmly opposed to them. The Kolel Ungarn (Hungarian

Community) in Jerusalem (see *Halukkah (Ḥalukkah)) was a

center of extremist opposition to Zionism in Erez Israel

(Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of Israel]], and the *Neurei Karta

faction later developed from it. (col. 1095)

[[The racist Herzl fantasy

of a "Jewish State" combined with nationalism = Zionism

The racist Theodor Herzl wrote a fantasy booklet "The Jewish

State", published in 1896 with the description of a new

"Israel", and the Arabs could be driven away as the natives

in the "USA", the Arabs would be the slaves of the Jews, and

perhaps gold could be found in Palestine and the gold mines

would be in Jewish hands as in South Africa. This racist

fantasy of Theodor Herzl was normal for it's time, because

racism was also accepted at the universities which also were

racist and had racist structures. The Herzl fantasy of a

"Jewish State" combined with the Moses fantasy of a "Greater

Israel" with the borderlines from the Nile to the Euphrates

according to 1st Mose chapter 15 phrase 18 (see the Bible).

Since this time there was Arab opposition against this

stupid fantasy of a racist "Jewish State", and since 1948

there is the Middle East conflict as an eternal war trap.

Herzl lead the Jews into an eternal war. The main fault that

to be Jewish is a religion and not a nation was not seen by

the racist Zionists. And the main culprit of anti-Semitism -

the criminal anti-Semitic Church which has not changed it's

stupid "New Testament" until today - was not seen by the

racist Zionists either...]]

[Numbers of 1910]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Hungary, vol. 8, col. 1105.

Drawing of the Jewish quarter

of Mármoros Sziget, from J. Pennell, "The Jews at Home",

London 1892

Before World War I [[1910?]] 55-60% of the total number of

merchants were Jews, approximately 13% of the independent

craftsmen, 13% of owners of large and medium-sized estates,

and 45% of the contractors. Of those professionally engaged

in literature and the arts, 26% were Jews (of the

journalists, 42%), in law, 45%, and in medicine, 49%. On the

other hand, only a small number of Jews were employed in

public administration.

The Jewish population numbered 910,000 in 1910. The

identification of the Jews with the Magyar element in the

Hungarian kingdom was an important factor in determining the

general political attitude toward them. (col. 1090) [[...]]

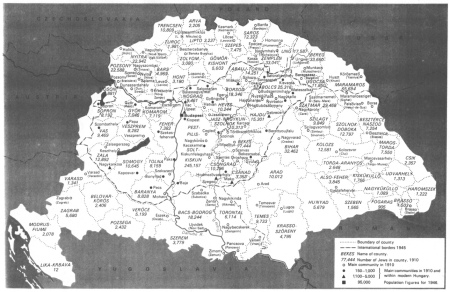

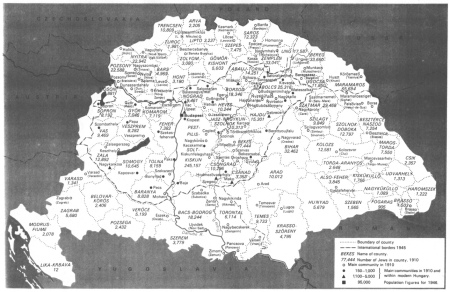

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Hungary, vol. 8, col.

1093-1094. Map of Hungery in 1910

with the numbers of Jews according to the counting of 1910

During World War I

the Jews suffered losses in life (about 10,000 Jews fell on

the battlefield) and property. At the same time, anti-Jewish

feeling was strong having increased because of the presence

of numerous Jewish refugees from Galicia, which had been

occupied by the Russians, and through the activities of Jews

in the war economy. (col. 1091)

[[At the end in 1917-1918 Communists were coming up, the

"Red Light" was coming from Moscow step by step to Central

Europe. Hungary had to accept the Trianon treaty and was cut

from all sides and many Hungarians were under foreign law

from CSSR, Ukraine, Romania, Yugoslavia, and little Austria.

By this there were migrations and hunger in Hungary because

many did not want to accept another nationality]].

index next