Encyclopaedia Judaica

Anti-Semitism 1700-1914 in Europe

Enlightenment - roots and writers - observances questions - economic envy - Jews as a national enemy in the new national states - emancipation and "Christian" hatred against emancipated Jews - "capitalist spirit" against "national spirit" - German anti-Semitic spirit with Wagner and Chamberlain - French anti-Semitism with scapegoat manner and Dreyfus affair - Romania - Austro-Hungarian Empire

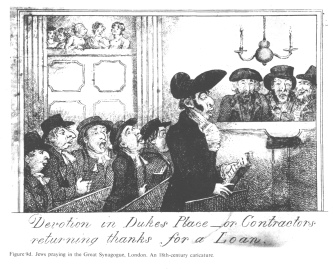

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 141-142b: Jews praying in the Great Synagogue, London.

An 18th-century cartoon. "Devotion in Dukes Place - or Contractors returning thanks for a Loan."

from: Anti-Semitism; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 3

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Share:

|

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<The Enlightenment

[The crusade against "Christian" racism - "Christians" and Jews have the same roots - writers]

For as long as Christianity held unchallenged sway in Europe, Jews could exist only on the margin of European social life. With the coming of the 18th-century Enlightenment, however, their isolation slowly began to crumble. A new class of bourgeois intellectuals - the philosophes - denounced [[racist]] Christianity in the name of Deism, or "natural religion", and ushered in the secularism of the modern era. As a result of their efforts, for the first time in centuries the status of the Jews became a matter for widespread debate. Many philosophes found it only natural to sympathize with the Jews. Not only were Jews the oppressed people par excellence in a century which prided itself on its concern for justice, but they were also the most notorious victims of [[racist]] Christian intolerance, which the Enlightenment was sworn to destroy.

Accordingly, protests against the persecution of Jews - and especially against the Inquisition, the Enlightenment's bête noire [[black sheep]] - became one of the standard set pieces of 18th-century rhetoric. Led by *Montesquieu, *Lessing, and *Rousseau, Enlightenment writers everywhere preached that Christian and Jew shared a common humanity and common human rights. Relatively few of these men foresaw the Emancipation, which for most of the 18th century remained a distant prospect. But emancipation was proposed as early as 1714 by the English freethinker John Toland, and it drew increasing support from philosphes as the century went on. When, at last, the Jews of France were emancipated in 1791, it was largely the authority of the Enlightenment which overcame the objections of churchmen and gentile economic interests.

Despite its achievements, however, the Enlightenment's pro-Jewish agitation was not so purely humanitarian as it appeared. Much of the indignation which Jewish suffering aroused was calculated not to comfort the Jews, but to exploit their plight for the purpose of condemning Christianity. Admiring accounts of the Jewish religion, such as those favored by Lessing, were also intended to discredit Christianity - often so blatantly that, like Lessing's famous Nathan der Weise [[Nathan the Wise]], they expounded Judaism as a religion for philosophes to make Christianity seem backward by comparison.

[Jews are mostly wanted to give up their "observances"- envy of Jewish economic success]

In short, when the Enlightenment chose to defend the Jews, it did so largely for reasons of its own; and it dealt with them, in consequence, not as real individuals, but as a useful abstraction. The sole novelty of its approach was that, whereas the Jews had once been a witness to the truth of Christianity, now they were expected to demonstrate its error. The actual Jews, meanwhile, were usually regarded with suspicion and distaste. The Judaism which they practiced, after all, was a religion much like Christianity and hence to the Enlightenment a "superstition" to be eradicated. What was still more serious, Judaism was often considered a particularly anti-social religion, one which nurtured a stubborn sense of particularism and created grave divisions within the state. These opinions were so widely held by Enlightenment writers that even friends of the Jews continually urged them to abandon their traditions and observances. Only Montesquieu, of all the 18th century's great thinkers, showed any willingness to accept the Jews without reforming them into something else.

Indeed, the most common argument for emancipation, as conceived by *Dohm, *Mirabeau, and other,s was precisely that it would convert the Jews to the majority culture, thus expunging their most obnoxious traits. This view was ultimately upheld by the French revolutionaries, who declared, when they emancipated the Jews in 1791: "To the (col. 111)

man, everything; to the Jew, nothing." Though as a citizen the Jews was to receive full rights, as a Jew he was to count for nothing.

Even so, this program of compulsive emancipation did not fully reflect the intense Jew-hatred of the more extreme philosophes. Though it is surprising to recall the fact, among this group were some of the leading minds of the 18th century, including *Diderot, d'*Holbach, and *Voltaire. Despite their intellectual stature, these men launched scurrilous attacks on the Jews which far surpassed the bounds of reasoned criticism. Many of their polemics were not only intolerant, but so vicious and spiteful as to compare with all but the crudest propaganda of our own day. To some extent, this anti-Jewish fervor can be understood as merely one aspect of the Enlightenment's war on Christianity. Diderot, d'Holbach, Voltaire, and their followers were the most radical anti-Christians of their time, and - in contrast to the more moderate Deists who praised the Jews - they did not hesitate to pour scorn on Christianity by reviling its Jewish origins. This tactic was all the more useful because Judaism, unlike Christianity, could be abused in print without fear of prosecution; but even the fact that the Jews made a convenient whipping-boy cannot explain all the hostility which they excited.

"Enlightened" diatribes [[propaganda attacks]] against Jews were often so bitter, so peculiarly violent, that they can only have stemmed from a profound emotional antagonism - a hatred nourished not only by dislike of Jewish particularism, refurbished from ancient Greco-Roman sources, but also by unconscious Christian prejudice and resentment of Jewish economic success. Voltaire, in particular, detested the Jews with vehement passion. A large part of his whole enormous output was devoted to lurid tales of Jewish credulity and fanaticism, which he viewed as dangerous threats to European culture. At times, Voltaire actually pressed this argument so far as to imply that Jews were ignorant by nature, and could never be integrated into a modern society.

To be sure, racist ideas of this kind made little headway against the ingrained egalitarianism of the Enlightenment. Neither Voltaire nor any other pre-Revolutionary thinker seriously denied that Jews could be assimilated, so that in this sense, at least, anti-Semitism was hardly known. Still less respectable were outright fantasies like the blood libel, which most Enlightenment writers firmly repudiated [[refused]].

[The new definition of the Jews as an "enemy of the modern secular state"]

Yet the fact remains that, for all their resistance to racism and other delusions [[ideas]], some of the leaders of the Enlightenment played a central role in the development of anti-Semitic ideology. By declaring the Jew an enemy of the modern secular state, they refurbished the anti-Semitism of the Middle Ages and set it on an entirely new path. In so doing, moreover, they revealed a depth of feeling against Jews which was wholly disproportionate to the Jews' supposed faults, and which would continue to inspire anti-Semitism even when the Jews' secularism was no longer open to question.

[P.W.]> (col. 112)

<Emancipation and Reaction

[Anti-Semitism before - anti-Semitism as the "hatred of a stranger"]

The newer 19th-century version of anti-Semitism arose on a soil which had been watered for many centuries in Europe by Christian theology and, more important, by popular catechisms. The [[racist]] Christian centuries had persecuted Jews for theological reasons, but this "teaching of contempt" had set the seal on the most ancient of all anti-Semitic themes: that the Jews were a uniquely alien element within human society. In every permutation of European politics and economics within the course of the century, the question of the alienness [[enmity]] of the Jew reappeared as an issue of quite different quality from all of the other conflicts of a stormy age. Jews themselves tended to imagine that their troubles represented the (col. 112)

time-lag of older, medieval Christian attitudes, of the anger at "Christ-killers" and "Christ-rejecters", which would eventually disappear. It was not until the work of Leo *Pinsker and [[racist ]] Theodor *Herzl, the founders of modern [[racist]] Zionism, that the suggestion was made that anti-Semitism in all of its varieties was, at its very root, a form of xenophobia, the hatred of a stranger - the oldest, most complicated, and most virulent example of such hatred - and that the end of the medieval era of faith and politics did not, therefore, mean the end of anti-Semitism.

[Jewish "emancipation" in France and in the criminal racist "USA"]

As a result of both the French and the American revolutions there were two states in the world at the beginning of the 19th century in which, in constitutional theory, Jews were now equal citizens before the law.

[[The main purpose for the racist "Christian" leaders was that the Jews could be drawn into their armies - in the criminal racist "United States" for the destruction and elimination of the First Nations (natives, "Indians"), the First Nations Holocaust]].

In neither case was their emancipation complete. In the [[criminal racist]] U.S. certain legal disabilities continued to exist in some of the individual states and the effort for their removal encountered some re-echoes of older Christian prejudices. The Jews in America were, however, at the beginning of the 19th century a mere handful, less than 3,000 in a national population approaching 4,000,000, and there was therefore no contemporary social base for the rise of a serious anti-Semitic reaction.

[Emancipation is worsening the economic conflicts in Europe - racist "Christians" are afraid of emancipated Jews]

The issues were different in Europe. In France there had been more than a century of economic conflict between Jewish small-scale moneylenders, illegal artisans, and petty credit and their gentile clients and competitors. The legal emancipation of the Jews did not still [[calm down]] these angers but, on the contrary, exacerbated [[worsened]] them. The spokesmen of the political left in eastern France during the era of the Revolution and even into the age of *Napoleon argued, without exception that the new legal equality for the Jews would not act to assimilate them as "useful and productive citizens" into the main body of the French people but, rather that it would open new avenues for the rapacity of these aliens. Napoleon's own activities in relation to the Jewish question, including the calling of his famous French *Sanhedrin in 1807, were under the impact of two themes: the desire to make the Jews assimilate more rapidly and the attempt, through a decree that announced a ten-year moratorium on debts owed to Jews in eastern France, to calm the angers of their enemies. On the other hand, Jews were visibly and notoriously the beneficiaries of the Revolution. It was, indeed, true that a number of distinguished émigrés had been helped to escape by former associates who were Jews, and it was even true that the bulk of the Jewish community, at least at the very beginning of the Revolution and a few years later during the Terror, feared rather than favored the new regime.

Nonetheless, in the minds of the major losers, the men of the old order and especially of the [[racist criminal "Christian]] church, the Jews were the chief, or at the very least the most obvious, winners during the era of the Revolution. The association of French anti-Semitism with counterrevolutionary forces, with royalist-clericalist reaction, throughout the next 150 years was thus begun very early. In the demonology of anti-Semitism it was not difficult to transform the Sanhedrin in Paris in 1807 into a meeting of a secret society of Jews plotting to take over the world. This connection was made in that year by Abbé *Barruel in his book Mémoire pour servir a l'histoire du jacobinisme [["Memory to Serve at History of Jacobinism"]]. This volume is the source of all of the later elaborations of the myth of the Elders of Zion.

In Europe as a whole a new kind of anti-Semitism was evoked by the new kind of war that the revolutionary armies, and the far more successful armies of Napoleon, were waging against their enemies. Between 1790 and 1815 the armies of France appeared everywhere not, as they announced, as conquerors holding foreign territory for ransom or for annexation, but as liberators of the peoples from the yoke of their existing governments in order to help (col. 113)

them regenerate themselves in a new state of freedom. Wherever the Revolution spread, its legislation included, in places as far-flung as Westphalia,Italy, and even briefly, Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of Israel]], equality for Jews. It was entirely reasonable on the part of the Austrian police, and the secret services of some of the other European powers, to suspect that some of the Jews within their borders were really partisans of Napoleon.

[Restricted emancipation since 1815 - steps for emancipation and envy of Jewish economic success - the fight about the "capitalist spirit"]

In the wake of his defeat the emancipation of the Jews remained on the books in France, but it was removed elsewhere, with some modifications in favor of Jews, as an imposition of a foreign power. The battle for Jewish equality had to begin again; it became part of a century-long battle in Europe to achieve the liberal revolution everywhere. This struggle had not yet ended by the time of World War I, for at that moment the largest Jewish community in the world, that in the Russian Empire, was not yet emancipated and had, indeed, suffered grievously throughout the century.

In the early and middle years of the 19th century, the most important battleground between Jews and their enemies was in Germany. Capitalism was rapidly remaking the social structure and Jews were the most easily identifiable element among the "new men". The victims of the rising capitalist order, especially the lower-middle classes, found their scapegoat in the most vulnerable group among the successful, the Jews. In a different part of society, and from a nationalist perspective, the most distinguished of German historians of the day, Heinrich *Treitschke, was insisting toward the end of the century that the acculturated and legally emancipated Jews, who thought in their own minds that they had become thoroughly German, were really aliens who still had to remake themselves from the ground up and to disappear inconspicuously.

Not long after the turn of the century Werner *Sombart (Die Juden und das Wirtschaftsleben [[Jews and Economic Life]] 1911) was to express his own ambivalence about capitalism as a whole by insisting, against Max Weber, that it was the Jews, and not the Protestants, who had always been, even in biblical days, the inventors and bearers of the capitalist spirit. Such identification between the Jews and the spirit of capitalism had been made, to their discredit, seven decades earlier, in 1844, by the young Karl *Marx in his essay "On the Jewish Question". for anti-Semites of both the political right and the left, who hated capitalism for different reasons, such identification was one of the sources and (col. 114)

rationales of Jew-hatred throughout the modern era, into the Nazi period. Hatreds rooted in class conflict combined with angers which derived from visions of national and cultural authenticity to produce the most violent and murderous attack on Jews in all history.> (col. 115)

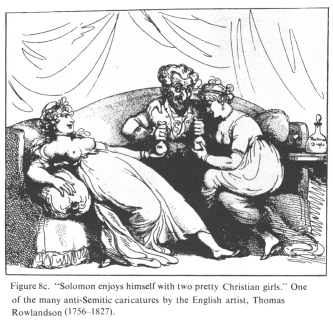

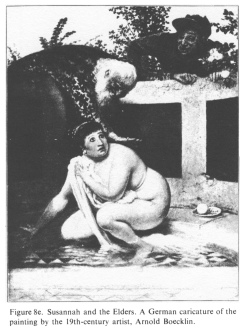

["Christian" defamation of Jews with cartoons in 19th century]

[The defamation strategy with the pork]

[The defamation strategy of having sex with "Christian" women and incontrollable Jewish potency]

[The defamation strategy with the love of money]

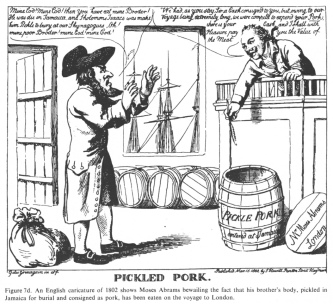

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 141-142a: a Rowlandson cartoon of

two Jewish moneylenders drawing up a bond with a young aristocrat

German anti-Semitism since 1819

[The "German spirit" is nothing for Jews - anti-Semitic works by Richard Wagner - son-in-law Stewart Chamberlain - ideal of unification as "Germans"]

On the surface of events modern German anti-Semitism began with riots by the peasants in 1819, using the rhetoric of older Christian hatreds. This hatred of Jews was soon transformed by the rising romanticism and the nationalist reactions to the Napoleonic wars into an assertion [[declaration]] that the true German spirit, which had arisen in the Teutonic forests, was an organic and lasting identity in which the Jews could not, by his very nature, participate. For this purpose the work of *Gobineau on race was pressed into service to make the point that the Jews were a non-Aryan, Oriental element whose very nature was of a different modality. Richard *Wagner insisted on this point not only in his overt anti-Semitic utterances but also indirectly in his operas, in which he crystallized the Teutonic myths as a quasi-religious expression of the authentic German spirit.

In Wagner's footsteps there appeared the works of his son-in-law, Houston Stewart *Chamberlain (The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century; 1899), which pronounced the presence of Jews in German society to be radically inimical to its very health. In the popular mind these theorists of national culture were understood within a situation in which the intellectual importance of Germany in Europe was not equaled by its political significance, for the scandalous division of the country lasted until 1870. To be united and German was the dominant ideal.

[The idea of the "Cosmopolitan Jew" - equality of 1859 in Prussia and since 1870 in whole Germany without social base]

The very difficulties in realizing the unity of Germany brought the existence of Jews into unfriendly focus. Very few elements in mid-19th century Germany society, even among their friends, were willing to regard Jews as true Germans. Jews were asking for political equality more in the name of the universal rights of man - that is, as partisans of the cosmopolitan principle - than as sons of the German people. As a result, the ultimate attainment of equality, first in Prussia in 1859 and ultimately in all of Germany in the aftermath of the unification of the country in 1870, had a quite narrow social base. It was identified with the rise of the bourgeois liberalism, but this element never dominated in mid-19th-century Germany as it did in contemporary England.

[Jewish competition against "Christian" middle class - reaction of the "Christian" middle class - Socialism]

What was worse, from a Jewish perspective, was that as a middle-class element the Jews were themselves in competition with the very class which had facilitated their entry into society. Toward the end of the century the German middle class itself was shifting its political alignment from liberalism to romantic conservatism. To be sure, the main thrust of German liberalism continued to regard anti-Semitism as reactionary, just as the main body of German Socialism would have no truck with the identification of all Jews with the capitalist (col. 115)

oppressors of the working class.

[Anti-Semitism with a mix of envy and myths]

[[The speculation system of the international stock exchange, the change of structures by industrialization, and the some rich Jews like Rothschild brought up a new hatred against the Jews, when Jewish bosses bought farms and set the German farmers into their industries...]]

Nonetheless, anti-Semitism was sufficiently potent for all its themes to coalesce into the image of the successful, non-national, unproductive foreigner, whose power resided in money and in his mastery of the legerdemain of modern manipulation. This "Jew" was a lineal descendant of the Jewish maker of love potions in Greco-Roman demonology and the poisoner of wells of the medieval myths, but the new version was very up to date and answered to contemporary frustrations and angers.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, anti-Semitism became an acceptable element in German political life to be manipulated at opportune moments by political leaders seeking popular lower-middle-class support. The very term anti-Semitism had been invented by Wilhelm Marr in 1879 and it was in that year that the court chaplain, Adolph *Stoecker, had made his first public anti-Semitic speech, "What We Demand of Modern Jewry", and had then turned his Christian Socialist Party in overtly anti-Jewish directions. With the rise of German imperialism toward the end of the century and the sense of success it gave [[racist kaiser]] Germany,political anti-Semitism waned, but social distance continued unhaltered.

French anti-Semitism since 1815

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 143-144a: cartoon of Rothschild, a French cartoon

by C. Léandre, 1898 [[showing Rothschild as an old and wild half-bird taking the whole globe]]

[French Jews in French society after 1815 - anti-Semitism from the extreme left and right - Industrial Revolution and the Jew as a scapegoat - defeat of 1870 and the Jews as a scapegoat]

In France, Jews had not been an issue of any considerable importance after the restoration of the Bourbons to power in 1815. There alone Jewish political gains had been safeguarded without question, because the fundamental social changes which had been introduced by the Revolution could not be radically altered by the return of the émigrés.

Nonetheless, Jews remained one of the most visible symbols of these very changes, and the attacks upon Jews, both from the extreme right and the extreme left, were sufficiently overt to provide the spark for greater difficulties in the second half of the century. Two of the greatest theorists of Socialism in France, *Proudhon and *Fourier, were anti-Jewish on the ground that Jewish capitalist interests stood counter to those of the peasants and the workers, and that the Jewish spirit as a whole was antithetical to their vision of a reformed humanity living the life of unselfish social justice. In France, too, the changes being brought about by capitalism and the Industrial Revolution made many people feel helpless, as their lives were being remade for the worse.

The power of the *Rothschilds was very evident in France, especially in the age of Louis Napoleon, and some of the anger at the new age came to expression in attacks on them by left-wingers such as *Toussenel. In the time of conflict which followed the fall of France in 1870 major elements among all forces contending for power after the debacle could blame their troubles in the Jews.

In the renewed political battles of the 1870s and 1880s the overwhelming majority of the Jewish community in France was associated with the liberal republican forces against the conservative Catholics, who were enemies of the Republic. From 1879 to 1884 republican anti-clericals dominated in parliament and succeeded in freeing French education from clerical control. One of the building blocks of the almost successful counterrevolution of 1888, in which General Boulanger very nearly made an end of the Republic, was anti-Semitism. The myth that the small handful of Jews in France had enormous and highly dangerous power had been broadcast two years before in perhaps the single, most successful anti-Semitic and counterrevolutionary book ever published, Edouard *Drumont's La France Juive [["Jewish France"]], which went through innumerable editions.

[Dreyfus affair since 1894]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 115, French cartoon of Alfred Dreyfus, 1894

[[when he was blamed of espionage for racist kaiser Germany. Dreyfus is shown as a

dragon snake and the shield "traitre" (treacher)]]

Late in 1894 anti-Semitism became the central issue of French society and politics for at least a decade and the reechoes of the positions taken in those years can still be heard. Captain Alfred *Dreyfus, the first Jew to become a member of the general staff of the French army, was accused of spying for Germany. The (col. 116)

outcry against Dreyfus was joined not only by the clerical-royalist right but also by some elements of the French left. His ultimate vindication was the result of the exercise of moral conscience in the service of trough b a number of individuals more concerned about the preservation of the Republic than about the rights of Jews. (col. 123)

Anti-Semitism in Romania

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 152b: Mastheads of two Rumanian [[Romanian]] periodicals, 1899 and 1907

<In Romania, despite promises that had been made in the Berlin Convention of 1878, Jews were systematically excluded from most walks of life. Even the native born were declared to be foreigners, so that very few Jews held citizenship. There was little that Jews could do except attempt to flee in large numbers.> (col. 124)

[[The Romanian government applied the racist Zionist practice that Jews would be a nation, and by this all Jews were foreigners. The Romanian government did not make any difference between racist Zionists and non-Zionists, as it seems]].

Anti-Semitism in Austro-Hungarian Empire

<In the Austro-Hungarian Empire the blood libel was revived in 1899 in Bohemia, but this was only the most sensational case of a series that had begun in *Tisza-Eszlar, a small Hungarian village, in 1882. Much Jewish energy went into the defense against such charges. What was being debated was not so much the blatant lie of the blood accusation but rather the more fundamental issue of the moral integrity of Judaism and the Jew. This was, essentially, still medieval anti-Semitism, but more contemporary currents were running strong. There were deep national tensions within the multinational Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Jews were caught in the middle of all of the most embittered of these situations. In Bohemia they identified with the ruling Germans, to the chagrin and anger of Czech nationalists, but the local Germans nevertheless rejected the Jews as not true members of the Volk [[population]]. In Galicia, the poorest and most medieval of the Austro-Hungarian provinces, the dominant Poles could claim a majority over the Ukrainians only by counting the Jews as Poles, but that did not induce them to accept even those Jews who were polonizing themselves. The masses of Galician Jewry, almost a million at the turn of the century, were living in poverty that was abject even by Russian and Rumanian [[Romanian]] standards, with no hope of betterment.> (col. 124)

===

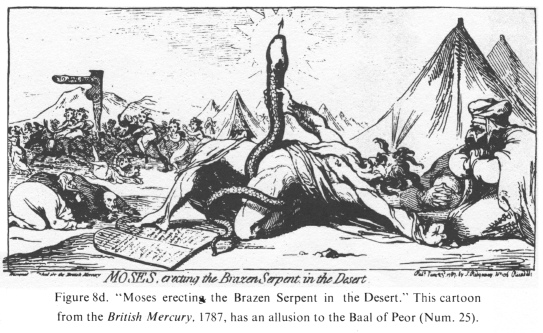

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 129-130a:

"Moses in the Bullrushes", by the

English caricaturist, G.M. Woodward, 1799.

[[Moses is making love in the corn fields]] Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 129-130a:

"Moses in the Bullrushes", by the

English caricaturist, G.M. Woodward, 1799.

[[Moses is making love in the corn fields]]](d/EncJud_anti-semitism-band3-kolonne129-130a-karikatur-Moses-im-feld-1799-25pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 131-132: [[a Jew

at a "Christian" prostitute,

paying five Francs with a 100 Francs bank

note]]. A cartoon by the French

caricaturist, H. Gerbault Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 131-132: [[a Jew

at a "Christian" prostitute,

paying five Francs with a 100 Francs bank

note]]. A cartoon by the French

caricaturist, H. Gerbault](d/EncJud_anti-semitism-band3-kolonne131-132-karikatur-nuttenbesuch-20jh-ca-33pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism,

vol. 3, col. 143-144a: cartoon of Rothschild, a French

cartoon by C. Léandre, 1898 [[showing Rothschild as an

old and wild half-bird taking the whole globe]] Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol.

3, col. 143-144a: cartoon of Rothschild, a French

cartoon by C. Léandre, 1898 [[showing Rothschild as an

old and wild half-bird taking the whole globe]]](d/EncJud_anti-semitism-band3-kolonne143-144a-karikatur-Rothschild-1898-35pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism,

vol. 3, col. 115, French cartoon of Alfred Dreyfus,

1894 [[when he was blamed of espionage for racist

kaiser Germany. Dreyfus is shown as a dragon snake and

the shield "traitre" (treacher)]] Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol.

3, col. 115, French cartoon of Alfred Dreyfus, 1894

[[when he was blamed of espionage for racist kaiser

Germany. Dreyfus is shown as a dragon snake and the

shield "traitre" (treacher)]]](d/EncJud_anti-semitism-band3-kolonne115-Dreyfus-karikatur1894-51pr.gif)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 152b: Mastheads of

two Rumanian [[Romanian]] periodicals, 1899

and 1907 Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 152b: Mastheads of

two Rumanian [[Romanian]] periodicals, 1899

and 1907](d/EncJud_anti-semitism-band3-kolonne152b-rum-antisem-ztgskoepfe1899-u-1907-39pr.gif)