[Racist czar and drive for

revolution - and more racist Czarist measures of

discrimination]

<There was a radical difference between the situation in

western Europe in the 19th century and that which prevailed i

the Russian Empire. At least in theory the West European

states were not anti-Jewish. Despite occasional

liberalizations, the [[criminal racist]] czarist regime as a

whole regarded it as its duty to protect the bulk of its

population against the spread of Jewish economic influence or

even of Jewish population. A few attempts in the course of the

century at the assimilation of the Jews did not alter the

basic outlook of the state, that Jews were dangerous aliens.

The [[criminal racist]] czar continued to derive the

validation of his absolutism from [[criminal racist

"Christian"]] theology, from the identification of the Caesar

and Jesus by the Orthodox faith; anti-Semitism based on

Christian religious prejudice thus remained alive and

virulent. Whatever hopes the Jews had in the course of the

19th century for improvement in their status rested in the

hopes for he evolution of czarist absolutism toward

parliamentary democracy.

Repeated repressions made such hopes clearly illusory, and

younger Jews in increasing numbers turned to helping to

prepare revolution. This served to enrage the [[racist

corrupt]] government, and the reactionary circles which

supported it, even further. The regime kept imposing more

economic disabilities on the Jews, keeping them in the least

secure of middlemen occupations such as petty shopkeepers,

innkeepers, and managers of estates for absentee [[not

present]] landlords; in these capacities Jews were in direct,

often unpleasant, contact with the poorest of the peasants.

The government made it its business to use these resentments

to draw attention away from the seething [[coming up]] angers

which pervaded the whole of the social system. Anti-Semitism

was thus encouraged and fostered as a tactical tool for

preserving [[criminal racist "Christian"]] czarist absolutism.

[Czar murdered in 1881 -

riots - all Jews are blamed - anti-Jewish economic

legislation since 1882 - anti-Semitic parties and

organizations, financed by the Czar - Beilis case]

The critically important event in the history of Russian

anti-Semitism took place in 1881, when a wave of pogroms

occurred involving outbreaks in some 160 cities and villages

of Russia. The occasion for these outrages was the

assassination of Czar Alexander II by revolutionary terrorists

on March 13, 1881. Among the assassins was one Jewish girls

who played a quite minor role, but reactionary newspapers

almost immediately began to whip up anti-Jewish sentiment. The

government probably did not directly organize these riots, but

it stood aside as Jews were murdered and pillaged, and the

regime used the immediate occasion to enact anti-Jewish

economic legislation in 1882 (the *May Laws).

The situation continued to deteriorate to such a degree that

in the next reign Czar *Nicholas II gave money to the

anti-Semitic organization, the Black Hundreds, and made no

secret of his personal membership, and that of the crown

prince, in that organization (see *Union of Russian People).

This body was associated with the government in directly

fomenting pogroms during the revolutionary years of 1903 and

1905; in that latter year the Protocols of the *

Elders of Zion was

published under the auspices of the secret police by the press

of the czar, although he himself believed the work to be a

fraud.

The ordeal [[public suicide]] of Mendel *Beilis arose within

the hysterical atmosphere of disintegrating czarism. He was

accused in 1911 in Kiev of ritual murder, and the full weight

of government power was put behind the prosecution. His

acquittal at the trial in 1913 was the culmination of two

years of battle between the regime and the Jews and their

supporters in liberal humanitarian circles in Russia and

throughout the world. (col. 123)

It was, indeed, in such circles, which were the Russian

parallel to the forces which had created western parliamentary

democracy and social and intellectual liberalism, that the

Jews found support during a tragic period. When these elements

came briefly to power in the revolution of February 1917 the

Jews were immediately given the rights of equal citizens.

Nonetheless, despite this later, brief, and abortive victory

of liberalism, after 1882 this current seemed to weak and

divided to afford the Jews much hope for the future. Men like

Turgenev had mixed feelings about Jews and even Tolstoy did

not always hasten to support them when they were under attack.

The political left was even more ambiguous. Even some of the

Jews within the general revolutionary movements saw the Jewish

petty bourgeoisie not as a victim but as an oppressor. The

anger of the peasants and the urban poor was, therefore,

regarded as merited, and their pogrom activities were even

viewed as positive stirrings toward the ultimate revolution.

This was, for example, the stand of the Narodniki, the

pro-peasant populist group, with regard to the pogroms of

1881. More fundamentally, the revolutionary groups in Russia

had even less patience with specifically Jewish problems, or

with any desires on the part of Jews to continue their own

communal identity. than was to be found in the European left

as a whole.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col.

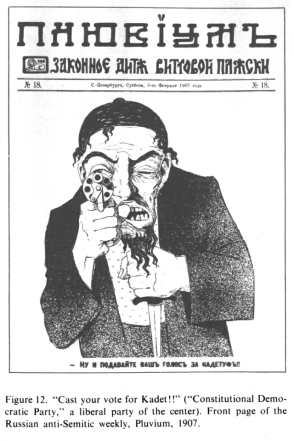

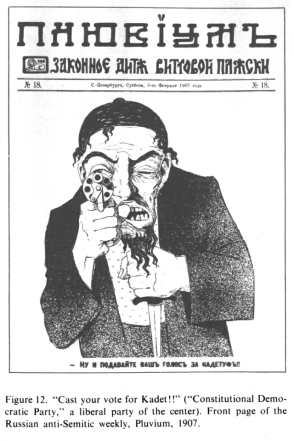

151b: cartoon of the election of Kadet in 1907

"Cast your vote for Kadet!!" ("Constitutional Democratic

Party", a liberal party of the center). Front page of the

Russian anti-Semitic weekly, Pluvium, 1907.

The young Lenin was an opponent of anti-Semitism, and he held

that the problems of the Jews would disappear along with that

of all other people in Russia in a new socialist order. On the

other hand, Lenin insisted that Jews would have to undergo a

mire radical and cultural transformation than any other

element in Russia and that any Jews who opposed assimilation

was "simply a nationalist philistine" ("The Position of the

Bund in the Party", in

Iskra,

Oct. 22, 1903).

Any form of Jewish association of feeling had already been

pronounced to be a form of particularly obnoxious reaction.

the stage was thus set for the ultimate questioning by Stalin

of the loyalty of even Communist Jews.> (col. 124)

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3,

col. 123-124

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Anti-Semitism, vol. 3,

col. 151-152 |