0. Introduction (summary)

The Red Earth: A Vietnamese Memoir of Life on a Colonial

Rubber Plantation

by Tran Tu Binh as told to Ha Anranslated by John

Spragens, Jr. - edited and introduced by David G. Marr

Ohio University Center for International Studies -

Monographs in International Studies

Center for Southeast Asian Studies - Southeast Asia Series

Number 66 - Athens, Ohio 1985 [p. III]

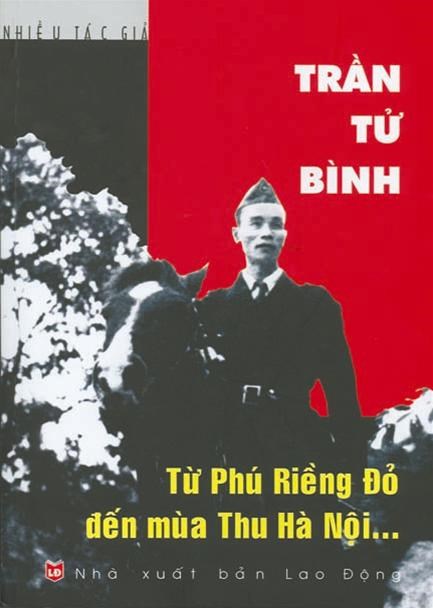

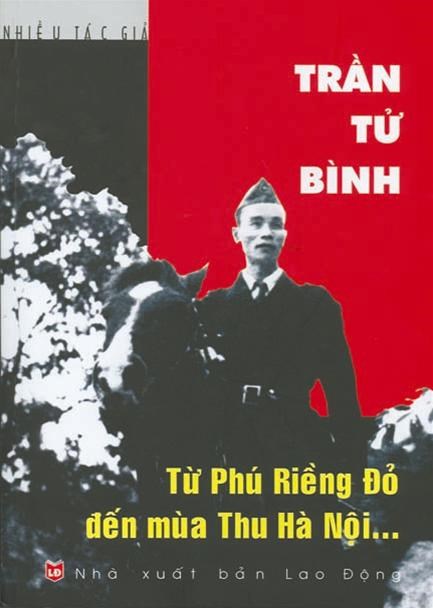

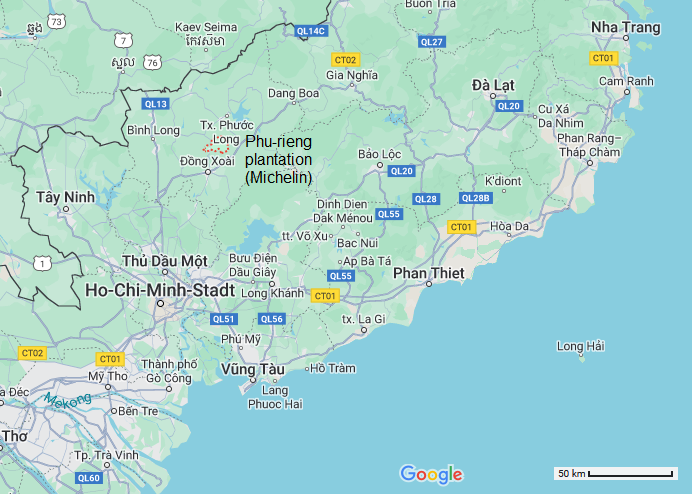

Tran Tu Binh 1949 [1] - map of Vietnam [map 01] -

book Tran Tu Binh on colonial rubber plantations

[2]

Tran Tu Binh was born May

1907 in an

all-Catholic [fantasy Jesus] Village in Ha-nam Province in

the Red River delta of northern Vietnam. His father

sustained the family by collecting and selling manure,

perhaps the lowliest occupation in the village. His mother

managed nevertheless to scrape together enough money to

enroll Tran Tu Binh at a [priests] seminary, where he

disappointed both of them in

1926 by being

expelled for publicly mourning the death of

Phan Chu Trinh, a prominent Vietnamese scholar-patriot. At

that moment, without yet knowing it, Tran Tu Binh joined

the ranks of the young intelligentsia, a group destined to

play a critical role in modern Vietnamese history.

[Tran becomes a fantasy Jesus Bible teacher - then

rejecting good jobs in the village - changing to South

Vietnam on rubber MONOplantations - he knows Lenin

principles]

As narrated with piquancy and verve in this autobiography,

Tran Tu Binh spent the next year as an itinerant

[fantasy

Jesus] Bible teacher, then signed up to labor

on a

rubber MONOplantation in the distant

red-earth region of southern Vietnam [

Cochinchina].

Although he doesn't say so, this was surely another severe

blow to the family. After all, even without any school

diploma, Tran Tu Binh

could have found a

respectable job as village clerk, landlord's agent, or

shopkeeper simply because he knew how to speak

and read French as well as Vietnamese. Instead he was

determined to break away, to seek adventure, to test his

physical and spiritual powers on totally unfamiliar

terrain. He was also vaguely familiar with the

Leninist

concept of "proletarianization", whereby young

intellectuals immersed themselves in a working-class

environment in order to engineer eventually the overthrow

of both foreign imperialists and native landlords.

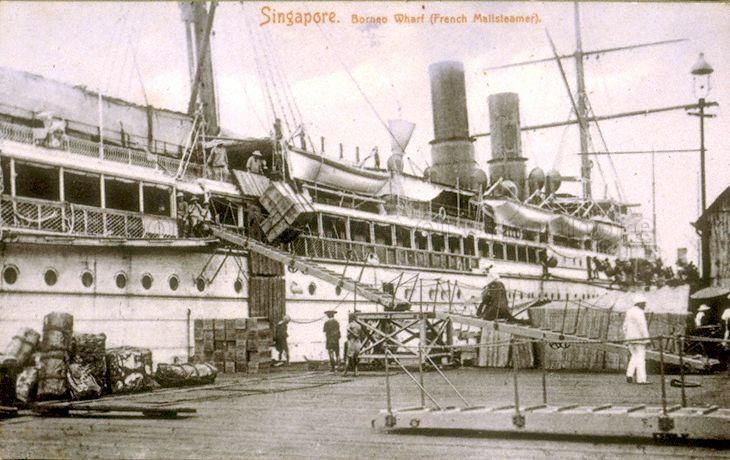

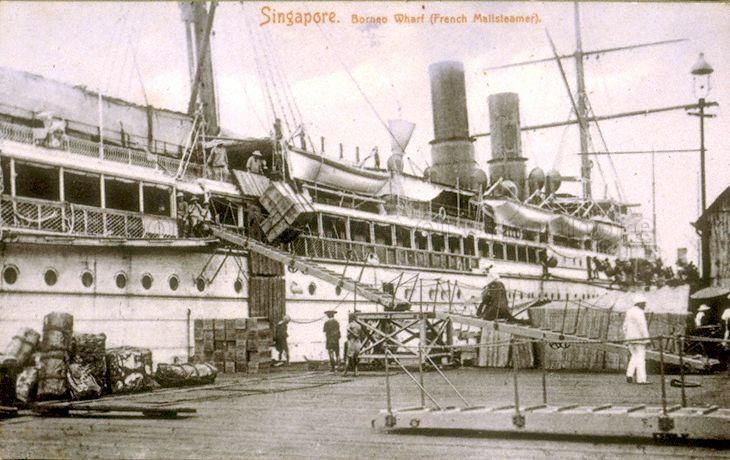

[Trip on the ship "Dorier" (French: "Golden") to South

Vietnam - docking in Saigon - fraud and fight for food

at the new MONOplantation "Phu Rieng"]

Even before boarding the French

ship Dorier

that was to take him south, Tran Tu Binh became embroiled

in a confrontation with plantation recruiting agents who

had defrauded hundreds of his illiterate fellow workers.

Because the agents feared that many contract workers might

simply pack up and return home, some satisfaction was

obtained; however, the atmosphere became more ominous the

further they traveled. When the ship

docked in

Saigon [in South Vietnam at the North end of

Cochinchina], workers were driven ashore like cattle and a

spokesman badly beaten for daring to complain. After being

trucked to a

tropical forest location 120km north

of Saigon, Tran Tu Binh found himself in truly

appalling physical and psychological circumstances.

France with steamers, e.g. at Singapore

in 1900 appr. [3] -

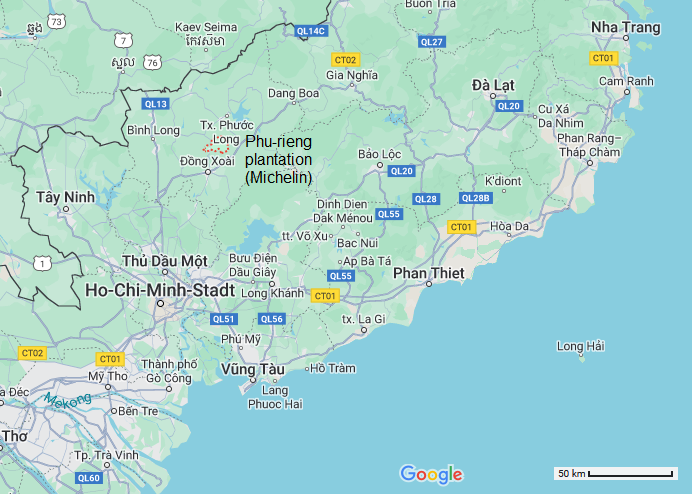

Map of

South Vietnam with HCMC (ex Saigon) and

Phu-rieng rubber MONOplantation in the

hills [map 02]

[The MONOplantation of] Phu

Rieng was one of about twenty-five French

rubber plantations that stretched in a three-hundred

kilometer band from the South China Sea to the Mekong

River in Cambodia [that is whole Cochinchina]. From

before World War i the colonial government had allocated

huge blocks of forest land to metropolitan corporations;

from 1920 on, large amounts of capital became available

to construct roads, nurture rubber seedlings, clear

land, and plant saplings.

[French colonies enslave natives from the same country

- Tran arriving in 1927]

Unlike the British in Malaya, who imported Indian or

Chinese nationals to develop rubber MONOestates,

the

French decided to use indigenous labor.

However, they soon discovered that the proto-Indonesian

[p. VII] tribes people who normally wandered this region

were quite unsuited to plantation work. Ethnic Vietnamese

who resided in and around Saigon, although they might be

lured on a seasonal basis, preferred not to sign

longer-term contracts. Besides, they were close enough to

home to walk away if conditions proved intolerable. These

facts led French rubber companies, with colonial

government encouragement and assistance, to focus

increasingly on recruiting contract laborers from the

heavily populated Red River delta provinces far to the

north. From a mere 3,022 contract laborers on southern

rubber MONOplantations in 1922, the number increased ten

times to 30,637 in 1930 [note 01]. Tran Tu Binh was one of

the 17,606 who arrived in

1927 alone.

[note 01] Pierre Brocheux: "The Rubber

Plantation Proletariat in Southern Vietnam: Social and

Political Aspects (1927-1937)" (orig. French: "Le

Prolétariat des plantations d'hévéas au Vietnam

méridional: aspects sociaux et politiques (1927-1937)";

[In]: Le Mouvement Social (Paris), no. 90 (January-March

1975): 63. The Great Depression reduced the number of

contract laborers to 10,800 in 1933, but five yeras later

the figure had risen to 17,022. [p.87]

[MONOplantations: rapes by plantation overseers - new

babies on the plantations - losses are concealed -

reports are also in Paris at the National Archives

(sector: oversees countries)]

Today's reader [year 1985] will perhaps be skeptical of

Tran Tu Binh's "hell-on-earth" description of Phu Rieng.

Admittedly, he employs poetic license on occasion. For

example, one finds it hard to believe that so many

husbands died of humililation and heartbreak after their

wives

had been raped by plantation overseers.

Nor does it seem likely that all

pregnancies

at Phu Rieng resulted in stillbirths. On the other hand,

many of Tran Tu Binh's grim assertions are confirmed in

confidential reports that colonial administrators

forwarded to Paris, and which are now available for study

in the National Archives of France (section oversees

countries (Archives Nationales de France - Section

Outre-Mer). For example, the minister of colonies is a

conservative figure, since

the plantation

supervisory staff had reason to cover up some losses.

Then, too, Tran TU Binh's characterization of Triair, the

plantation director, as particularly brutal is

corroborated in a

report of the governor general to

Paris ([note 02]: same place, pages 71 and 80

[p.87]). Overall, Tran's account of plantation life may be

assessed as exaggerated in tone, yet essentially reliable

in substance.

Rubber plantation in Vietnam: the French

"Christians" were stealing land from the

mountain natives Montagniards for

installing MONOplantations [4] "Christian"

torture and murder with sticks, whip and

shackles [5] - Violations

with fixed women, London tube

painting [6]

[Tran i the seminar testing the Canadian fantasy Jesus

priest Mr. Quy - 18 years later the Canadian priest Quy

is working in the prison of Hanoi]

One theme pervades The Red Earth: the existence of a

bitter test of wills between exploiter and exploited. We

see it first in Tran Tu Binh's confrontation with the

Canadian

[Jesus Fantasy] priest, Father Quy, which

culminates in a bit of Jesuit-like rhetorical jousting in

a

Hanoi prison eighteen years later. We see

it again in the author's argument with the captain of the

[ship]

Dorier on the way (en route) from

Haiphong to Saigon.

Jesus

fantasy priest is a FAKE (comic) [7] -

every Jesus fantasy priest is a spy,

THIS is the REALITY (comic) [8] - Slave

collar [9]

[Phu Rieng MONOplantation: constant terrorism against

the slaves - slaves partly develop counter strategies]

Most important, we are witness to the ruthless,

persistent

efforts of the Phu Rieng supervisory staff to tear

down the psychological defenses of Vietnamese workers

in order better to control them [constant

terrorism]. For at least one year these tactics -- akin to

those of

slave masters, prison workers, drill

sergeants since time immemorial -- enjoy

considerable success. Workers are clearly disoriented and

demoralized. Gradually, however,

some workers

recover internal poise, improvise protective tactics,

organize quietly, and plan countermeasures.

Ironically, they are assisted by Triair's less brutal

successor, [camp boss Mr.]

Vasser, who

allows them to form a variety of sporting, cultural, and

religious groups.

Slash and burn in a rain

forest, e.g. in Brasil [10] - Leg broken,

leg in a cast [11] - Cut with blood [12] - Skeleton

skull [13] - "Christian"

Machine gun [14]

[Phu Rieng MONOplantation: Tran with French knowledge

understands how the criminal French are thinking - the

"master" is the animal]

Because

Tran Tu Binh can understand French,

he is more aware than most of the nonphysical aspects of

oppression. He points out how each plantation staff member

styles himself [p. VIII] "

master" and

demands that workers use that form of address. Each

"master" refers to the Vietnamese as children or

animals.

One senses that such verbal abuse rankles Tran Tu Binh

even more than blows from the truncheon. It follows that

much of what he and his comrades do in response is an

attempt to prove to themselves, and perhaps to the French

as well, that they are resourceful adults who know how to

take destiny in hand.

[Phu Rieng MONOplantation: Tran with French becomes the

spokesman for the workers - job at the plantation clinic

- investigating wounds+"Christian" torture instruments -

forming of 4-person cells with members from Ho Chi Minh]

Tran Tu Binh's knowledge of French often led his fellow

workers to thrust him forward as

spokesman,

an inherently dangerous position. However, it also led to

his being employed as an orderly at the

plantation

clinic, a "soft" job (for which he continued

to be apologetic) clearly enabling him to

study the

enemy more carefully and to

make many

friends among the worker patients.

The clinic gives often only a "medicament" to

vomit [15]

When a member of

Ho Chi Minh's Revolutionary Youth

League came secretly to Phu Rieng [plantation]

he naturally sounded out the clever medical orderly. Soon

a

four-person cell was formed, followed

eventually by a Communist party branch with Tran Tu Binh

in charge of organizing a security unit.

[Phu Rieng MONOplantation: the workers learn

revolutionary tactics - killings provoke more killings -

colonial justice at Bien-hoa - dire conditions of

housing]

Although there was scant opportunity for formal political

instruction, plantation workers at Phu Rieng were not

devoid of

revolutionary experience. They

had already learned, for example, that to swear a blood

oath and

split open the head of a hated French

overseer brought a few moments of

satisfaction, but also

provoked terrible

retaliation. On the other hand, they had

discovered the futility of

relying on colonial

justice to punish the wicked. In one specific

case that advanced as far as a

court in Bien-hoa,

an overseer found guilty of negligent manslaughter was

sentenced to pay a token five piasters [the French

colonial currency in Indochina] to the victim's widow.

Workers also leaked stories to Saigon newspapers about the

dire conditions at Phu Rieng [plantation].

They devised a method to

sabotage rubber saplings

without being discovered.

Although such initiatives did induce the French to make

minor concessions, the basic system of exploitation

remained fixed.

[Vietnam Communist Party: against criminal "Christians"

with slavery+torture+mass murder - Michelin company -

better conditions - coup project - the coup against

Soumagnac at Tet Day (30 January 1930)]

The new Communist party's objectives at Phu Rieng

[plantation] were

-- to heighten class consciousness among plantation

workers,

-- to build an organization implicitly competing for power

with the

Michelin company hierarchy, and

-- to link local with regional and national struggles [for

a national independence with Buddha].

From Tran Tu Binh's account, it seems that by 1929 Phu

Rieng laborers were able to react quickly to

some

of the more flagrant cases of physical abuse

and to

gain redress from the plantation

director. Then they went a step further, demanding and

receiving

--

better food,

-- better medical care, and

-- boiled water to drink at work sites.

Excited by these gains, workers began to look toward a

general strike.

Recalling events thirty-four years later, Tran Tu Binh

still manages to convey the millenarian excitement that

gripped Phu Rieng workers in early 1930. The strike was

set to coincide with the Vietnamese Lunar New Year (Tet),

always a time of high emotion and spiritual renewal. Most

workers probably had in mind

overturning the evil

masters, enjoying a huge feast, and then proceeding to

operate the plantation themselves pending a

new deal from the authorities. Some workers sharpened

weapons in [p.IX] expectation of an armed uprising. Tran

Tu Binh makes it clear that the local Communist party

branch (of which he had become secretary) was of no mind

to try to hold back the movement, although it had no

authorization from higher echelons to proceed beyond a

simple strike. It did engage in rudimentary

contingency planning, ensuring that workers established

hidden food caches, and making a pact with some of the

local tribes people [Vietnamese mountain natives] whereby

the latter promised not to serve as strikebreakers for the

French.

The MONOplantation's director,

Soumagnac,

seems to have been poorly prepared for what happened from

the first day of Tet (30 January 1930) onward. Not until

his office was surrounded by angry workers three days

later did he telephone the nearest military post for

reinforcements. Somehow workers managed to disarm seven

soldiers and send an entire platoon into retreat. This

forced Soumagnac to sign a paper agreeing to all the

workers' demands, after which the festival of revolution

began, complete with

demonstrations, red flags,

speeches, singing of the "International", rifle

volleys in the air, burning of office files,

traditional opera performances, and a torchlight

banquet. All supervisory staff were allowed to

flee the MONOplantation.

Throughout the night of 2-3 February1930, the Communist

party branch met apart from the festivities ebating what

should be done next. To resist incoming troops meant

bloodshed, defeat, and repression. Not to resist meant

deflation of the movement, probable demoralization of the

workers. Similar dilemmas were encountered a few months

later by party members in a number of other locations,

most notably the provinces of Nge An and Ha Tinh. The

manner in which Tran Tu Binh and comrades dealt with their

own "moment of truth" provides valuable insight into a

much larger question of revolutionary strategy and

tactics.

[Death penalty or prison for the revolution leaders of

Phu Rieng MONOplantation - Tran 5 years on Con-Son

prison island - formation as Marxist-Leninist]

Whatever they decided, the Phu Rieng Strike leaders were

likely to be killed or captured. Tran Tu Binh was

arrested, tried, and sentenced to

5 years on the

infamous Con-Son prison island. There, like so

many other radical Vietnamese intellectuals, his

systematic

training as a Marxist-Leninist

began. Upon release the party designated him secretary of

his home district committee, then in 1939 promoted him to

be

Ha-nam province secretary. As a member

of the party's Northern Region Committee he helped

engineer the general

uprising in Hanoi in August

1945. Subsequently, he was

deputy

secretary of the party's Central Military Committee,

commander of the army's military academy,

and

chief inspector of the Vietnam People's Armed

Forces. In 1959 he was appointed ambassador to

China, and the following year was made a member of the

party's Central Committee. Tran TU Binh died in February

1967 and was honored posthumously wit a medal befitting

his long service to party, state and army ([note 03]: Nhan

Dan (Hanoi), 12 February 1967 [S.87]).

[BUT: Communism maintains exactly the same concentration

camps with Gulag systems as the "Christian"-Jewish stock

market capitalism in the colonies. Vietnam demolished the

last concentration camps in the 1970s, and South

Vietnamese fled from the communists on boats until the

1980s. The middle ground was only found after

perestroika].

Flag of the Soviet Union with hammer, sickle, and 5

pointed star with the WARNING GULAG [16] - Communist

leaders WARNING GULAG [17]

The Red Earth is a straightforward account of how one

Vietnamese youth became involved in revolutionary

politics, was tested amidst the most difficult conditions

imaginable, and not only survived, but also gained the

obvious respect of his peers [p.X]. Nevertheless, readers

will be aware that a number of Marxist-Leninist didactic

points are being made as the story progresses [but the

GULAG was forgotten to be mentioned]. Three times, for

example, Tran Tu Binh asserts that the more people are

oppressed the more they will struggle, a theme that Ho Chi

Minh stressed constantly, and that was also meant to be

applied by Vietnamese readers in 1964 to the growing

threat posed by the [criminal Zionist] United States. The

feasibility of

ethnic Vietnamese (Kinh) and

highland minority (Thuong) peoples joining to fight

a common foe is highlighted for the same reason. Only

passing mention is given to international

proletarian solidarity, since that sentiment was much

weaker in 1964 than it had been in 1930. Naturally "the

Communist party" is given credit at the end for every

significant achievement, although the narrative itself

suggests no such thing.

The Red Earth is one of more than a 100 memoirs published

since 1960 by veterans of the 1925-45 struggles in

Vietnam. Like many other busy luminaries, Tran Tu Binh

relied to some degree on a ghost writer, Ha An by name.

Although it is impossible to know how Ha An influenced the

narrative, a comparison of this book with certain others

suggests that Tran Tu Binh was entirely in control. The

story has a liveliness and sense of milieu that only one

who actually experienced the events could provide. If the

story is excessively dramatic in places, this stems from

spontaneous feelings of the participant, not the stylistic

devices of a literary cadre. In short, we have here an

authentic, edifying, and eminently readable autobiography.

David G. Marr